Barry Goldwater – Through the Lens

Writer Amanda Christmann

Photography Courtesy of the Barry and Peggy Goldwater Foundation

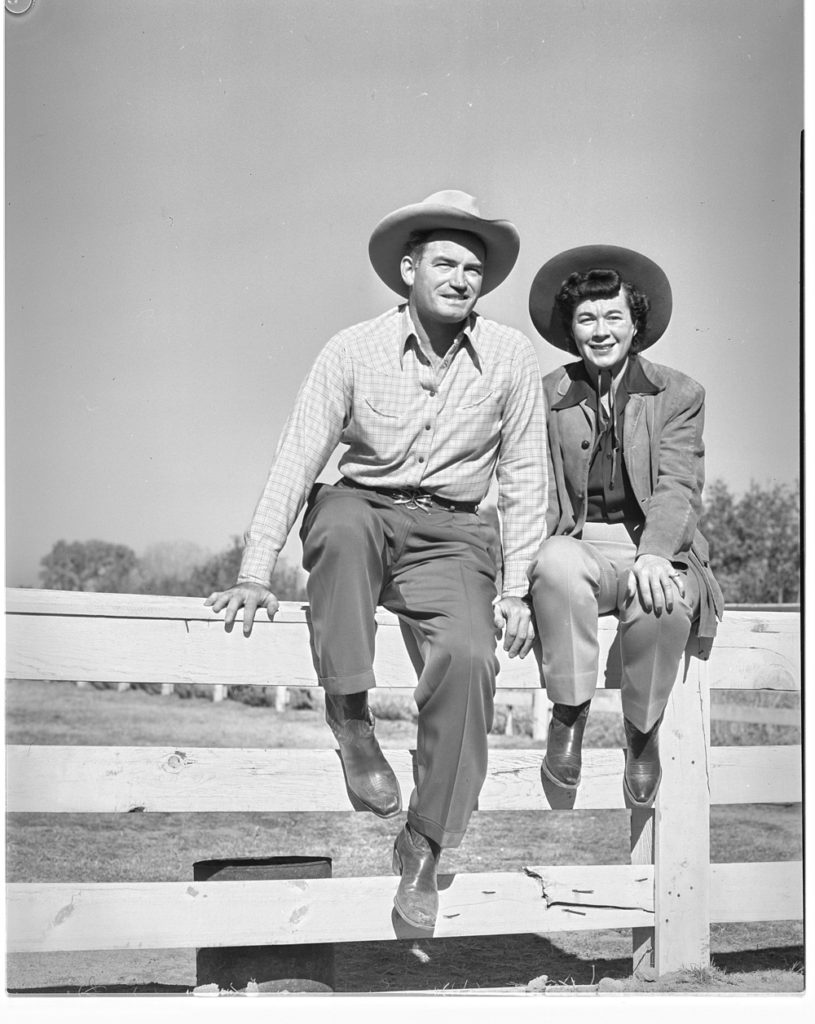

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the 1960s, an Arizonan entered the national political scene and forever redefined conservative politics. Sometimes referred to as a “real life John Wayne,” Barry Morris Goldwater all but rode into Washington on his horse, taking on the ideology of East Coast Republicans and, despite his landslide loss in the 1964 Presidential race, paving the way for Ronald Reagan and a new direction for the Republican party.

Love him or hate him, Barry Goldwater stood for what he believed in, even when he was the only one standing. Though his record appears at first glance to contradict itself (he was staunchly against the Civil Rights Act, but was a founding member of the Arizona NAACP and eliminated segregation in his family’s department stores, for example), his ultimate motivation was less federal regulation and more personal freedom—a decidedly libertarian slant to conservative politics.

Through the years, personal freedom became Goldwater’s war cry, and he would go on to fight for separation of religion and government, gay service members and women’s choice on abortion. For Goldwater, less government regulation was more, and he ruffled feathers on both sides of political lines.

Still, as a senator, he was widely respected. When evidence of scandal mounted against President Nixon, it was Goldwater who was sent to notify Nixon that, unless he resigned, he would be impeached by the House and removed by the Senate. Nixon resigned the next day, and a new term, “Goldwater moment,” was coined to describe times when an elected official is abandoned or openly opposed by his or her party.

Though he is often memorialized for his political contributions, Goldwater was passionate about so much more.

He and his first wife, Margaret, were married in 1934. On their first Christmas together, she lovingly presented him with a camera—a gift that would introduce him to a life-long love of photography.

Over the years, he would snap tens of thousands of photographs, including 15,000 images that would later be donated to three Arizona institutions. He would go on to publish three coffee table photography books: “Delightful Journey” first published in 1940 and reprinted in 1970; “People and Places” in 1967; and “Barry Goldwater and the Southwest,” in 1976, in which Ansel Adams wrote the foreword. Goldwater was also a regular contributor to Arizona Highways magazine.