Woven Into the Fabric

Writer Amanda Christmann

Product Photography by Carl Schultz

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the days before all that is, Diné people emerged from the third world and into the fourth. It was a time when monsters roamed the land, devouring people and creating chaos.

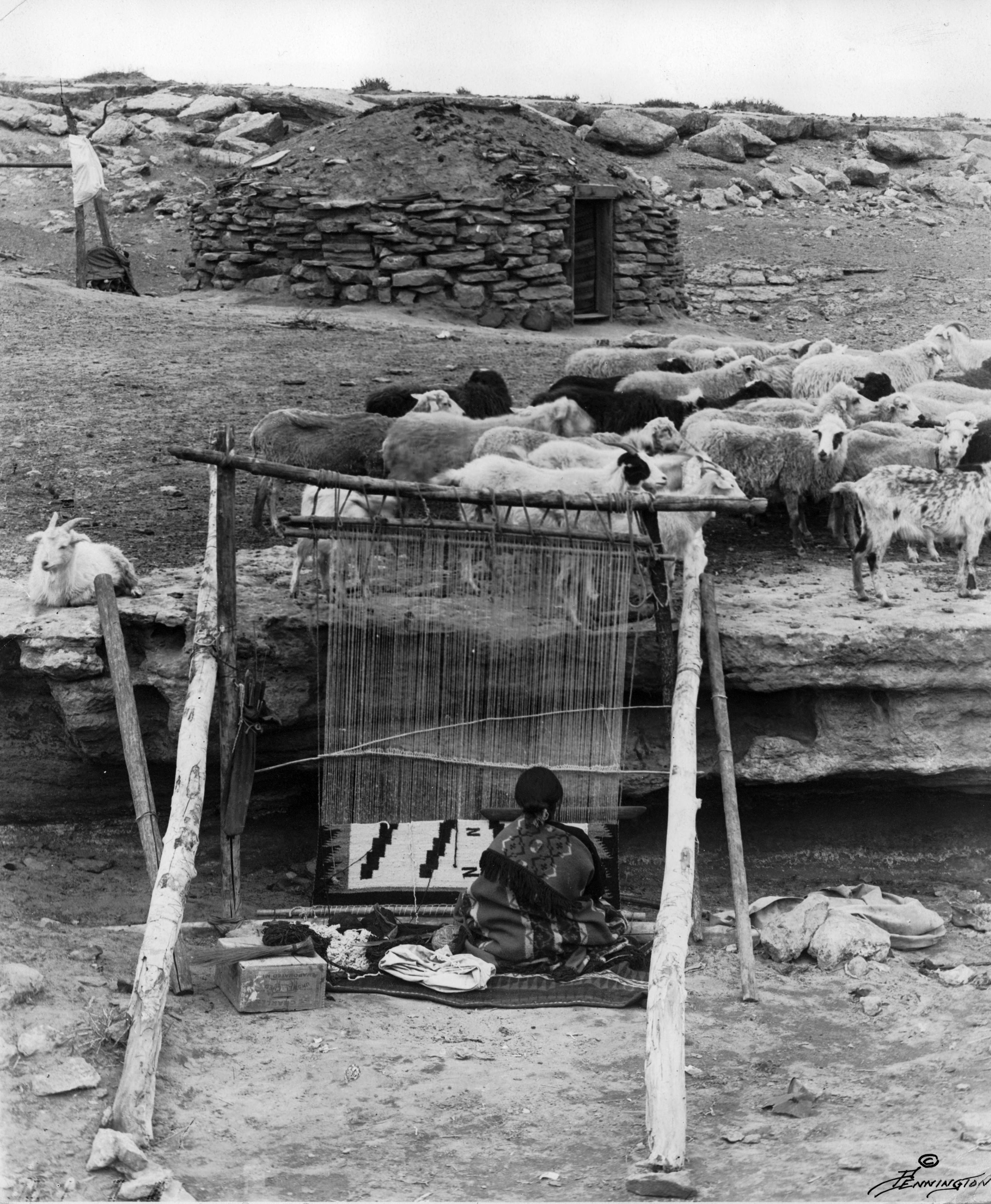

Spider Woman, who lived at the top of Spider Rock, loved the humans, so she sent other deities to guide and teach them. Her husband, Spider Man, constructed the first weaving loom, and it was Spider Woman who taught the Diné to weave, giving them a way to clothe and protect themselves.

It is stories of Spider Woman and other spirits, passed along for generation through songs, dances and ceremonies, that have shaped Navajo history. Traditions deeply rooted in these legends have become part of the Diné way of life. Navajo weaving is among the most vivid examples.

The Diné have always been weavers, but over time, straw baskets turned into simple shoulder wraps and dresses. With each generation, new ideas evolved into new materials, designs and uses. All the while, weaving was, and still is, a process that connects the human spirit to the earth and sky.

It was a pivotal era in history when Spanish colonizers brought sheep to the Desert Southwest. While weaving had always been sacred, the use of wool deepened the tradition. Master weavers could now raise sheep, treat their fleece and spin it into wool thread. They could then dye the thread and weave it into rugs and other textiles.

Throughout the process, weavers respect their sheep, blessing them for their contributions and acknowledging Spider Woman and the earth, sky, and generations who came before who passed along knowledge and skills.

Weaving only grew more important as European colonizers marched on—and over—Navajo lands and culture. After their homes and way of life had been taken away, it was weaving that gave Diné people something to trade for food, supplies and the basics they needed to survive.

Johnson explains: “I am not an expert, but I am a student of Navajo history, to a degree. From what I understand, in about 1868, the U.S. government rounded up all of the Navajo. They went on the Long March, a forced evacuation, and were removed from their own reservation onto a smaller one. They didn’t have any native wool, so they made what were Mexican rugs with machine-made yarn.

“In 1890, they were allowed to return to their old Red Rocks Country. The weavers were familiar with weaving, and where else were they going to get clothes?

“At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, the new design period that we talk about today began. The rugs that were made began to have such a mixture of designs and colorful elements that they were called ‘eye dazzlers.’ They were so beautiful.”

When Ken Johnson bought his first Navajo rug in 1958, he didn’t know much about it, or the hundreds of years of history behind it.

“At the time, I was a beginning reporter for the Grand Junction, Colorado newspaper,” he says. “I was making about $8 an hour, and the rug cost about a week’s pay.”

Johnson had no idea if his rug was worth anything special (it wasn’t). Still, he liked it and decided to invest in a few more.

“My first rugs were quite cheap,” he says with a laugh. “I started being more selective after a little while. I learned more about the colors—the vivid colors of Native-woven rugs captivated me.”

A man named Ed Austin would change things for Johnson. Austin was a salesman for a provisions company that was slowly dying. He’d found a market for his canned goods and wares on the reservation, where he’d drive along winding dirt roads from one unmarked trading post to the next, swapping goods for rugs.

“He went all over selling Indian rugs out of his trunk, from Durango to Monument Valley,” Johnson says. “The trading posts had excess rugs they wanted to sell. They didn’t have Amazon in those days, so people had to go to those old posts to find them. Of course, in the early days, unless you lived on the reservation, you wouldn’t know how to get to the trading posts if you wanted to.”

There was also not a lot of demand for Navajo rugs in the mid-20th century.

“Unless you were a gallery, there really wasn’t a market for them,” Johnson says. “Ed was able to buy rugs quite cheaply and pass them on to his other customers quite cheaply. He helped the traders and the Navajo by doing it.”

Over the next decade, Johnson bought two to three rugs to as many as 30 from Austin each year. He learned to how to feel of the weaving and learned how the various colors work together with the designs. He came to recognize an exceptional rug when he saw it.

When Cultures Collide

From the Navajo perspective, traders like Austin were a mixed blessing. On one hand, they created a market. Traders saw profits; weavers often saw their work as a way to maintain their spiritual craft while putting food on the table.

On the other, traders recognized that there was a limited market for traditional Navajo rugs. They began to heavily influence the look, feel and design of the rugs by requiring tighter weaves, more vivid colors and natural dyes.

Styles were developed around traders like John Moore at Two Gray Hills in New Mexico and Juan Hubbell, who operated a trading post in Ganado.

These traders became critical to Navajo survival, and also became part of the community. Though there was money to be made, they still often grew to care about people in the communities where they lived.

Traders also pushed weavers to create designs that were, by Navajo tradition, not meant to be used. That’s because some symbols were too sacred for the loom.

Johnson made a rather unusual find when he stumbled upon an undated rug with kachinas and symbols representing the four directions, along with other spiritual connotations.

In Navajo culture, the details in that rug are woven, and therefore a permanent depiction, of a sandpainting—something that simply wasn’t done in years gone by.

Of course, any interpretation of sandpaintings made by someone outside of the Navajo tribe is colored through a cultural lens, so a simplified explanation about what happens during a spiritual ceremony using them would be inaccurate at a minimum.

Sandpaintings are just as the name infers—colored sand used to paint a picture. They are used in spiritual ceremonies, particularly when someone is sick. A passable explanation would be that spirits are summoned to help heal the person, and then the sandpainting is destroyed, releasing the spirits into the wind.

To make a sandpainting permanent is to break natural law. The spirits cannot be released. Diné people believe that, if you break natural law, you will walk into the chaos you have released in the future.

The sandpainting rug that Johnson found was likely influenced by the will of the trader. Woven sometime in the middle of the last century, the trader probably requested the design because he knew it would sell. It was probably not something that the weaver’s family would have condoned.

Yet there it was. Johnson bought it.

Through the years, he collected several sandpainting rugs. Some he sold, but the majority have become part of a fantastic personal collection of fine and often rare Navajo textiles.

He, too, has learned to respect the traditions, processes and talent that go into making each rug. Now in his eighth decade, the rugs and their history have become part of his own life story.

“I still have rugs in my office and in my master walk-in closet,” he explains. “Every morning when I go in there, it just brightens my whole day to see those wonderful, vivid colors. To be able to put my bare feet on it does something for me.”

The Collection

“After 1968 or 1969, I had about 450 rugs,” he says. “Through the years, we just kept them.

“Twenty years later, we were living in Redstone, Colorado. It was a time warp. There were about 90 people living in it. It had been an old coal and steel baron’s idea to have his English countryside estate. The mansion, now called Redstone Castle, was built as a retreat in this remote 7,000-foot-elevation valley with the Crystal River running through it.

“There was a general store there, so they started selling some of our rugs. We sold about 80 rugs within a couple of years.”

Johnson whittled down his collection by giving some away to loved ones and selling others along the way.

“My collection is winnowed down to about 55 rugs,” he says. “We ended up with some incredibly valuable rugs and it’s a very unique collection.”

Remarkably, Grace Renee Gallery in Carefree now has more than 30 of these high-quality rugs and tapestries, with others available by catalog. They represent regional master weavers from Two Gray Hills, Teec Nos Pos, Crystal, Red Rock Trading and others.

“When they arrived last month, people began hearing by word of mouth that they were here,” says Shelly Spence, the gallery’s owner. “Their quality is exceptional, and collectors began coming in with magnifying glasses to see them. What they’re telling me is that these are some of the best quality Navajo rugs they’ve found. I’m really honored that Ken has chosen our gallery to sell them.”

It is rare to have more than 30 pieces from a personal collection all in one place, particularly because each rug and tapestry represents a piece of history.

“Generations of knowledge are built into each rug,” says Johnson. “They represent a way of life that we can all appreciate.

“They really are special.”

Ken Johnson Collection of Navajo Rugs

Oct. 4, 5 | Grace Renee Gallery | 10 a.m.–5 p.m. | Historic Spanish Village | 7212 E. Ho Hum Rd., #7, Carefree.

480-575-8080 | gracereneegallery.com