Writer Joseph J. Airdo

Photography Courtesy of HonorHealth, JW Marriott and Lincoln Electric

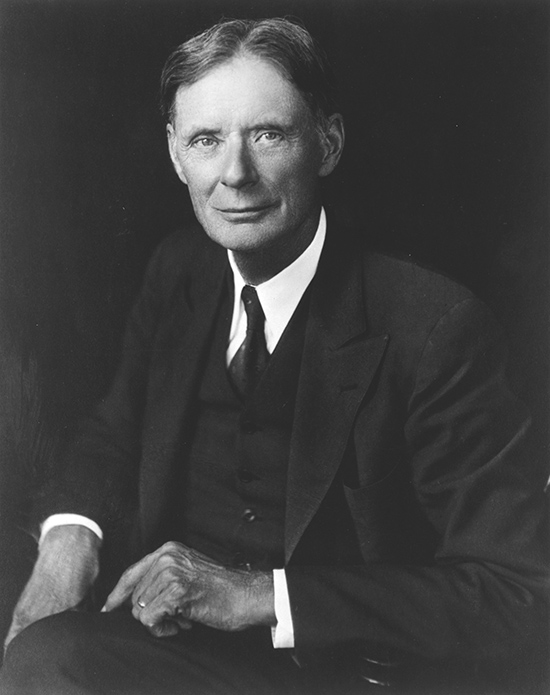

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ne of the Valley’s most well-known names in medicine was not a doctor at all. In fact, he was an electrical engineer who turned a capital investment of just $200 into some of Arizona’s most notable businesses.

John C. Lincoln will forever be known as one of the Valley’s most innovative business leaders. He used a little capital and a lot of forward thinking to create one of the country’s most reputable manufacturing companies, which then led to the creation of John C. Lincoln North Mountain Hospital, the Camelback Inn and other Arizona anchors.

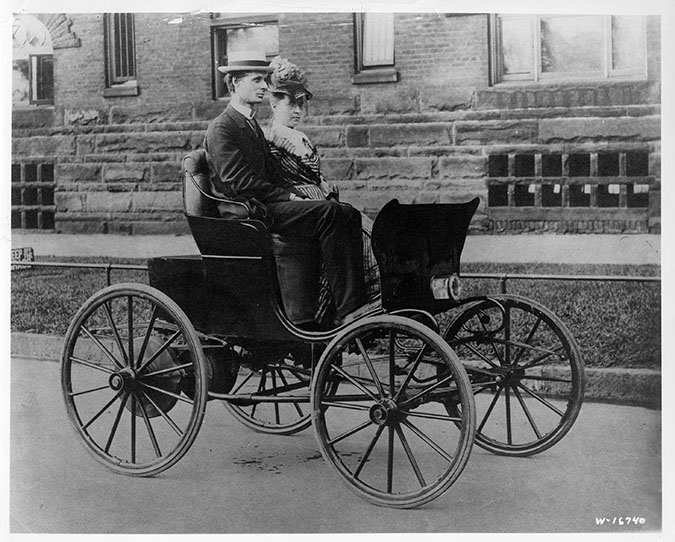

John Cromwell Lincoln was born July 17, 1866 in Painesville, Ohio. While in high school, he developed an interest in electrical engineering—an interest that he brought with him to Ohio State University. At the end of his third year in college, Lincoln felt as though he had learned all he could about electrical engineering in school and left without a degree.

Over the next seven years, Lincoln held positions at a number of electric companies and even set up a small shop in his home where he took on small jobs. One of his personal clients, Herbert Henry Dow, paid Lincoln $200 to redesign a motor—a capital investment he used to found the Lincoln Electric Company.

“He is a notable entrepreneur,” says Arizona State University emeritus history professor Dr. Philip VanderMeer. “He fits into a category or class of people throughout the country who were developing companies in the very late 19th and early 20th centuries and expanding these companies with a lot of innovation and intelligence.”

Lincoln used his company to conduct research and to experiment with the electrical devices that he invented. By the end of his life, he was granted 54 patents for a variety of inventions—from variable speed electric motors to electric arc lamps and welding metals.

“He was very innovative,” Dr. VanderMeer says. “He was an industrialist but he was also doing research and developing patents and so forth. He is quite interesting in that sense. Lincoln Electric took advantage of new technology by working on motors and batteries, then it became quite important because of its work with building.”

Lincoln’s work with the Lincoln Electric Company was so significant that, in 1913, Ohio State University awarded him an electrical engineering degree honoris causa. The degree was predated to 1888—the year he left the college.

It was at the Lincoln Electric Company that he also developed an interest in welfare capitalism, introducing programs that benefitted his workers like paid vacations, employee stock ownership, an employee suggestion program and incentive bonus programs.

Improving Arizona’s Healthcare

Lincoln’s first and second wives—Myrtle Virginia Humphrey and Mary Dearstyne Mackenzie—passed away in 1913 and 1917, respectively. In 1918, at the age of 52, Lincoln married Helen Colvill. The pair first visited Arizona in 1930 and, shortly thereafter, they decided to move to the Valley.

Helen had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, and it was believed that Arizona’s dry air and climate was better than that of Ohio for respiratory illnesses. They made their home near 32nd Street and Camelback Road, buying 320 acres—most of which they obtained by paying delinquent taxes, amounting to about $20 per acre.

“You generally see a pattern of people migrating to different areas, but people moving for health issues is not something that is restricted to particular economic classes,” Dr. VanderMeer says. “When someone as wealthy as Lincoln is pulled to the Valley because of the health benefits, they begin looking around for opportunities. He had the capital, the skills and the contacts. All of those were real advantages in terms of economic development in the Valley.”

Helen recovered within two years and, in 1933, the couple became involved with the Desert Mission—a comprehensive, faith-based community center founded by the First Presbyterian Church in 1927 in Sunnyslope. The facility provided medical, social and religious services, with a focus on tuberculosis sufferers, to those who could otherwise not afford it.

In 1938, Lincoln and his wife gifted the organization $2,000 to purchase 20 acres of land between Dunlap and Hatcher and from Second and Third streets, and eventually helped expand it into the area’s first medical clinic and emergency station.

Lincoln often covered the operating expenses of the fledgling hospital, which was renamed John C. Lincoln North Mountain Hospital in 1954 in honor of his significant contributions to its concept and construction.

HonorHealth’s John C. Lincoln Medical Center occupies the location today with 262 beds and one of the first level-one trauma centers in the Valley.

Making Phoenix More Cosmopolitan

Lincoln made many other real estate investments after arriving in Arizona, with one of the most notable being a 300-acre parcel situated between Mummy and Camelback Mountains in Paradise Valley.

Sportswriter and publicist Jack Stewart approached Lincoln with the idea of building a pueblo-style hotel that would reflect the Southwestern and Native American cultures. Lincoln agreed, received stock in payment for the land and even contributed the cash necessary for the initial construction of what would become the Camelback Inn.

“This was an area that was ripe for development,” Dr. VanderMeer says. “Lincoln was always one for sensing good business opportunities and he took advantage of this. It was quite important to have the kinds of facilities that would attract people of wealth who wound up benefitting development in the Valley.”

The Camelback Inn opened Dec. 15, 1936 with accommodations for 77 guests. Lincoln served as president of the resort, which became a popular destination for Hollywood celebrities and political leaders. Its earliest visitors included Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Bette Davis and J.W. Marriott, Sr.—whose son would later buy the resort.

Lincoln’s other real estate investments included 2,400 acres of land near Higley; 70 acres of citrus near Mesa; and a 2,000-acre ranch with 197,000 acres of range land rights in Yuma County.

Lincoln’s charitable contributions continued as well, as he helped build the main lodge at the YMCA Sky-Y Camp in Prescott in 1938 and a new YMCA facility in downtown Phoenix in 1944.

Lincoln was also involved in Arizona’s copper interests, initially leasing the old Vulture Mine near Wickenburg only to later abandon mining efforts there during World War II. In 1944, he was named president of the Bagdad Copper Company.

“True to form, Lincoln began looking into different technological innovations and ways to improve the operation,” Dr. VanderMeer adds.

Changing the Way We Look—and See

Lincoln remained very busy during his later years, writing books and pamphlets on land and land taxation, providing economics lectures and establishing the Lincoln Foundation, which continues to contribute substantially to the Henry George School in N.Y. and the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy in Cambridge, Mass.

“He remained active until the end of his life,” Dr. VanderMeer says. “He was still mentally alert and interested in the larger issues and causes that drove him most of his adult life.”

Lincoln was experimenting with high-speed crushing rolls when he died on May 24, 1959, at the age of 92. Two years later, he was posthumously granted his 55th patent for a spring cushion that is still utilized in automotive seats today. And in 1998, he was finally inducted into the American Mining Hall of Fame.

“John C. Lincoln is a person who had an impact on Phoenix through the hospital that he developed, through Camelback Inn and through the Lincoln Institute, which has partly headquartered here in the Valley,” Dr. VanderMeer says. “But I think that he is also illustrative of the way in which Phoenix has always been connected to the rest of the country.

“Here is a guy who reflects an impulse that inspired reformers across the country. Lincoln was part of that, starting in the 1890s, and he maintained that enthusiasm throughout his entire life.

“He had a way of raising issues and important questions that people here needed to grapple with, and he is one of the people who made the Valley more cosmopolitan and connected it to the rest of the world.”

Comments by Admin