Jack Lengyel: He is Marshall

Writer Tom Scanlon

Photographer Bryan Black

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he idea of a football game — and just about any honest coach will confide this — is to dominate the opponent.

You want to impose your will, showing your opponent a speedy route to the cold, hard turf. You want your rivals to limp back to the sideline as you dance in the end zone.

Win big, if you can, but even if it takes a Clemson-in-the-college-playoffs or Patriots-in-the-Super-Bowl thrilling score in the final seconds, make sure you come out ahead in the end so that, when the clock ticks down to 0:0, you get to enjoy the chest bumps and man-hugs and Gatorade showers while your whipped opponents hang their heads on that long, shamed trudge back to the losers’ locker room.

Oh, yes, football is all about winning at all costs.

Except during one magical season when the scoreboard didn’t matter for little Marshall University in West Virginia.

This was 1971, the season after a plane crash that killed nearly the entire team, plus the coaches, boosters and others connected with the program. In the 2006 production “We Are Marshall,” a rising star named Matthew McConaughey played Jack Lengyel, who was hired not only to coach the team, but also to resurrect the program.

In the movie, McConaughey-as-Lengyel philosophizes about the thousands of times he has heard, and preached, “Winning is everything,” the phrase that fuels football.

“And then I came here. For the first time in my life, maybe for the first time in the history of sports, suddenly, it’s just not true anymore. At least not here, not now. It doesn’t matter if we win or if we lose. It’s not even about how we play the game. What matters is that we play the game. That we take the field, that we suit up on Saturdays, and we keep this program alive.”

The real Jack Lengyel says that wasn’t some Hollywood fancy speech; he really said that, or at least something very close.

“It really wasn’t about winning,” he said, looking back at that challenging season, 46 years distant. “It was about getting a team together to begin the process of rebuilding. We realized we were going to have to do things differently. We were going to have to change the way we coach.”

With an inexperienced squad of freshmen, transfers, volunteers from other sports, and a few surviving members who were not on the plane, Lengyel’s team somehow won Marshall’s first home game after the crash — and the homecoming game. But the 1971 team lost the other eight of its 10 games, with five shutouts and a string of lopsided losses.

And yet, it was a resoundingly victorious season. In a Sept. 7, 1971 letter to Coach Lengyel, his staff and the team, then-President Richard Nixon summed up the feelings of many:

“The 1970 varsity players could have little greater tribute paid to their memory than the determination to field a team this year. Friends across the land will be rooting for you, but whatever the season brings, you have already won your greatest victory by putting the 1971 varsity squad on the field.”

Lengyel had been a coach at the College of Wooster, 230 miles north of Marshall University, when he learned of the tragic plane crash. Wooster had just finished one of its most successful seasons.

“I was home with my family,” Lengyel recalled, “watching a television show, and a crawl came across ‘Marshall University football team perished in a crash.’”

He didn’t think of contacting the school right away, until a few months passed, and he heard Marshall was having trouble filling the position.

“They offered the job to a coach at Penn State but he turned it down. Another coach took the job and resigned. I got to thinking, ‘Maybe I can help.’ I called down there, and they invited me down.”

Over the years, he’s been asked many times why he took the toughest job imaginable. Why leave a successful run as a young coach at Wooster, where he had an impressive 24-12 record in four years, to tackle the unknown?

“There’s an old Chinese proverb,” Lengyel will tell you, with a twinkle in his eye. “If you’re ever given something of value, you have a moral obligation to pass it on to others.”

So it was that Lengyel passed on to the young players all the football knowledge and worldview he had gathered. Though his record was an unspectacular 9-33, in his four years at Marshall he helped save a program that would become a powerhouse in the 1990s.

A few years later, in the spirit of his “Charlie’s Angels,” director McG (Joseph McGinty Nichol) directed a script based on what could be called “Jack’s Angels.”

“We Are Marshall” opened Christmas week, 2006. Reviews were mixed, ranging from “thrilling and wrenching” to “misbegotten tribute”; it turned a slim profit, grossing $43 million at the box office.

Though there were a few Hollywood touches in the script, Lengyel said the producers “did a good job” telling the story, and he still watches his copy, once or twice a year.

The energetic performance by McConaughey, who had just been named People magazine’s “Sexiest Man Alive,” is central to the movie. Though the facts are in place, Lengyel has a hard time seeing himself in the movie. A chat he had with the star during the production helped explain the curious circumstance of watching someone play him — or perhaps an alternate-universe version of him.

“People say to me, ‘He doesn’t have your mannerisms, at all,’” Lengyel said, with a chuckle. “Well, I remember walking back off the field one night during the filming with Matthew. He put his arm around me and said, ‘My dad was a football coach…’ So he had some feel for coaches. He did his research and read about me, but he said, ‘I didn’t try to mimic you. I took the material and put it inside myself.’

“I said, ‘I’m glad you told me that, because I was never that frickin’ animated on the sidelines!’”

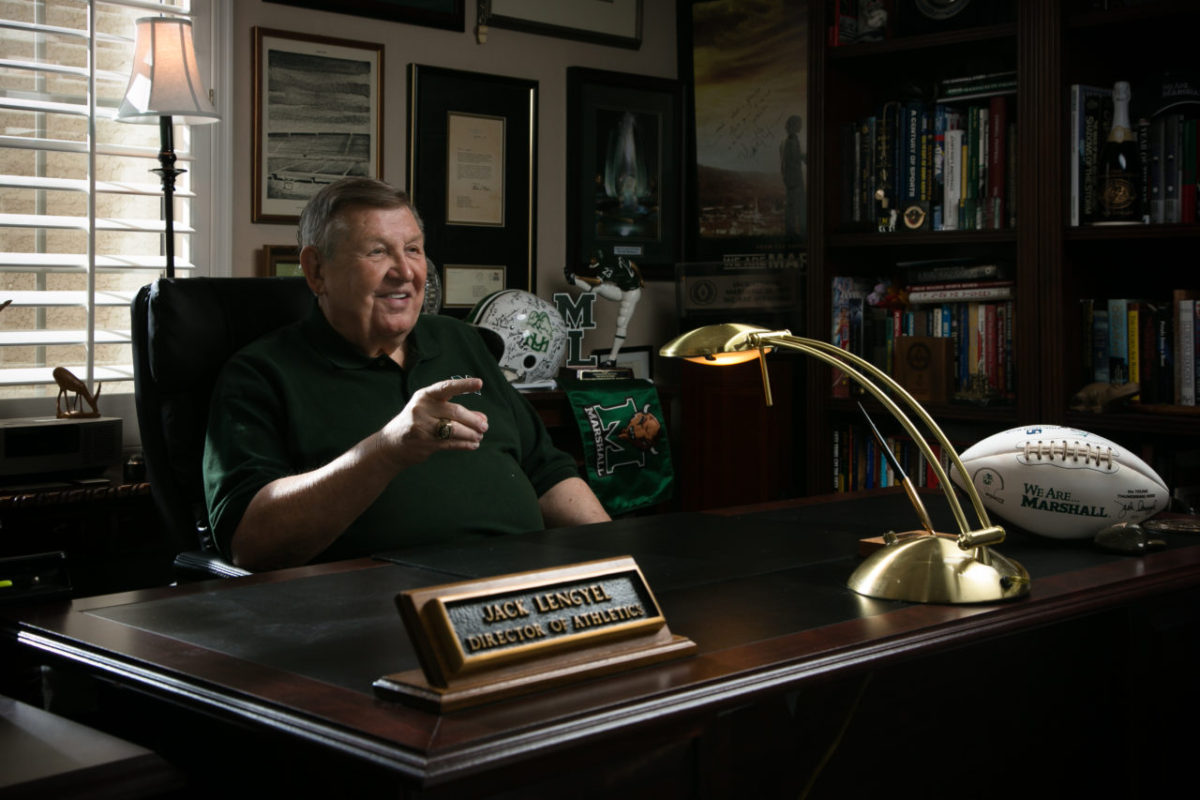

Sitting at the dining room table of his Sun City Grand home, Lengyel breaks into a wide grin when an F-35 military plane roars overhead. “The sound of freedom,” said Lengyel. He is quite familiar with the roar of military planes, as he was athletic director at the United States Naval Academy from 1988 to 2001.

In the big picture, Lengyel’s four-year stint at Marshall was just a slice of a long career as a football coach and athletic director. His home is filled with photos and mementoes documenting his two legacies, professional and personal. After moving 24 times in his coast-to-coast career, he and Sandy, his wife of 60 years, settled in Arizona a dozen years ago to help her arthritis. They enjoy visits with their three children, sons David and Peter, daughter Julie Logan, grandchildren and now great-grandchildren.

Retired as a coach/administrator, the 82-year-old Jack Lengyel serves on several football boards, chairing the Divisional Hall of Fame Board at the National Football Foundation and College Hall of Fame. In general, he remains enthusiastically active in the sport that has had him captivated for decades.

As the movie coach stated and the real Lengyel confirmed, coaching at a school rising out of deep sorrow taught him that winning at Marshall wasn’t the most important issue.

Well, let’s take it a step further. Why, Jack Lengyel, does football matter at all? Why should thousands of college kids who have no hope of playing professionally waste their time running around, slamming into each other when they could be studying?

Jack Lengyel has thought about this, and he is convinced that his favorite sport is a worthy endeavor — and then some.

“Football’s a game that enhances so many of the characteristics you need to be successful in life,” Lengyel said with the patience of a coach explaining a play to a freshman quarterback. “You develop character, perseverance, respect and teamwork. You learn lessons, even from losing.

“… Football provides one of the best lessons in athletics and life: to face adversity, get back up off the ground and go on to success.”

One thing the ol’ coach treasures is hearing from former players, especially when they say, “You know, now that I have kids of my own, I get what you used to tell me!” Just an example, Jack Lengyel says, of the life lessons hiding inside the country’s most popular sport.

“It’s a game that teaches you to be selfless,” said this leathery football man. “There are things you can’t learn in the classroom, born out of camaraderie, and those are friends who become lifetime friends.

“These are lessons that are valuable in the business, in the community and in life.”

There are only three words to add to that: We Are Marshall.