Randy O’Brien ceramics

Writer Beth Duckett

Photographer Wilson Graham

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]andy O’Brien’s journey from fledgling art student to acclaimed potter has led him to some very interesting places — and people.

Before settling at his current home in the foothills of southern Arizona, O’Brien lived in California, where he studied under well-known ceramics artist Al Johnsen. He also launched a pottery studio in Alaska before experimenting with pottery glazes at a New York university, a process that led to the striking, one-of-a-kind glazed surfaces he is known for today.

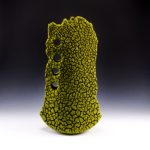

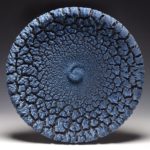

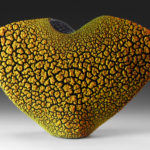

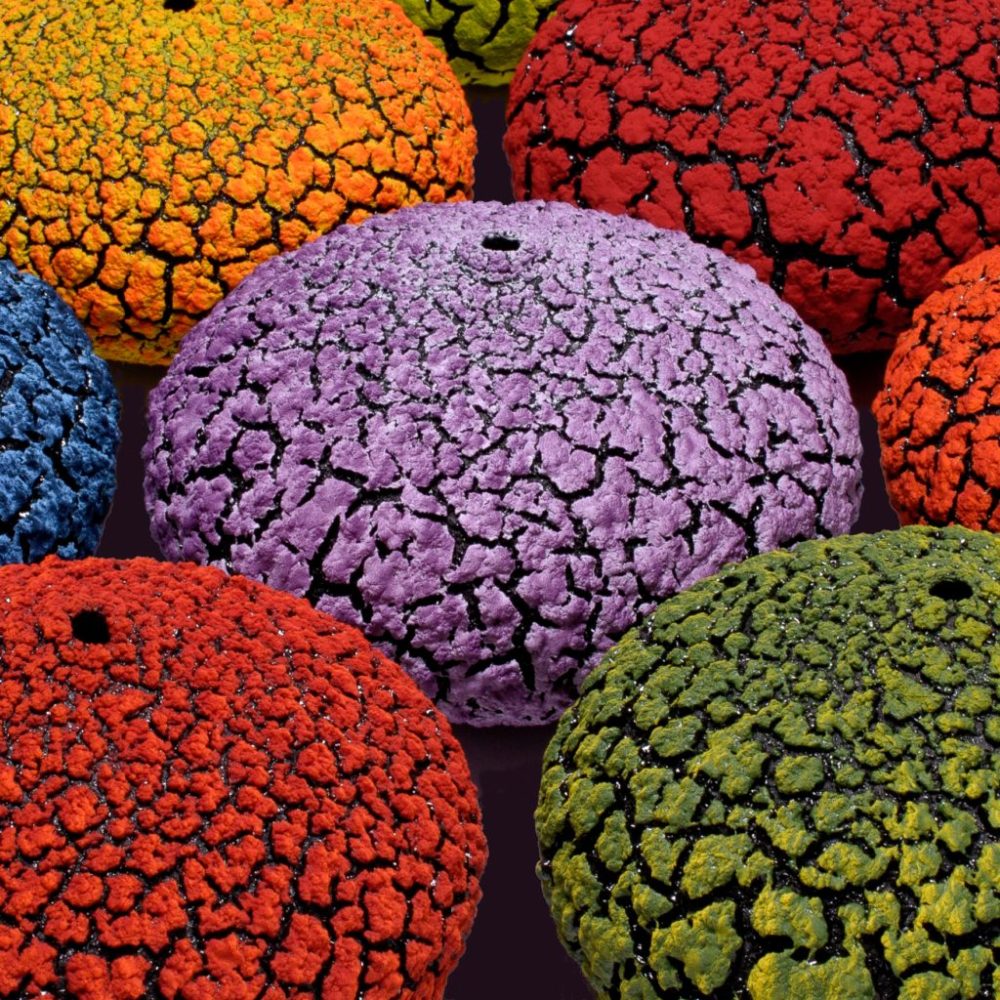

O’Brien says of his style, which resembles the mineral formations and lichens found in southern Arizona: “If anyone sees it, they know that’s my work.”

With such a repertoire of places traveled, you might think O’Brien has taken the opportunity to also journey to art shows across the country. But the potter primarily sold through galleries for much of his career. It wasn’t until the recession that O’Brien began to explore the art world beyond his comfort zone.

“For a large part of my life, I wanted to hole up in my studio and make pots,” the artist recalls. “I had about 24 galleries before the recession. It got down to six. I had to try and reinvent how I made a living.”

Now, O’Brien shows at about a dozen fairs annually, gaining crucial feedback from collectors that he didn’t get previously. “It has been great for my growth,” he says. “It has been great to interact with people.”

Additionally, O’Brien works with about a dozen galleries across the country, from California to Illinois. June Dale, owner of the Austin Presence gift shop in West Lake Hills, Texas owns several of O’Brien’s pieces, noting that they have a “mystery about them, because they look like they could come from outer space, under the sea or from a volcano.”

O’Brien’s work “combines brilliant color and amazing texture to create a piece that is both organic and otherworldly,” says Mesia Hachadorian of Tubac, Arizona-based Cobalt Fine Arts Gallery.

“It is hard to have a Randy O’Brien piece in a room and not have it draw your eye,” Hachadorian notes. “There is not a day that goes by that someone doesn’t walk into the gallery and ask me, ‘How does he do that?’”

Similarly, New Mexico artist Barbara Meikle, who represents O’Brien at her namesake fine art gallery in Santa Fe, says his pieces “add a delightful element” to any room. “His unique process has an organic quality that is hard to resist; the unusually bright colors combined with the deep texture always stirs the curiosity of collectors as they come through our door,” she says.

O’Brien began his career as a young student at the University of California, Berkeley, enrolling there in the early 1980s after spending a year as a foreign exchange student in Malaysia.

Of his travels abroad, O’Brien remarks: “I went into some pottery studios there. When I got back to the states, I went to school. At that point, I didn’t really consider making a living making pots. I just spent all the time I possibly could in the studio.”

O’Brien left Berkeley and later attended the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he had access to a pottery studio 24 hours a day. Santa Cruz is also where he met late accomplished painter and potter from Gig Harbor, Washington, Al Johnsen, who hosted workshops there throughout the summer. After about three years, Johnsen hired O’Brien to work in his studio. “I made some of his pots while he painted,” O’Brien says. “I did that for about a year.”

With several years of schooling under his belt, O’Brien was experienced enough to take his career to the next step.

He moved to Homer, a quaint tourist-friendly city in south-central Alaska, and pursued his dream of owning an art studio.

“It took me six months,” the potter remarks. “I rented a studio I found it had been abandoned. It had all the equipment. I ended up in a number of different locations.”

Nicknamed “the cosmic hamlet by the sea,” Homer is on the west side of the Kenai Peninsula on the shore of Kachemak Bay, which is home to a sprawling wilderness park. Naturally, O’Brien found inspiration for his work in the innate splendor of the area. He recalls the winters in Homer, which often lasted nine months or longer; icicles would form on the sides of cabins and expand until the temperature finally warmed up in the summer.

Inspired by the aesthetics of his surroundings, O’Brien tried placing bits of glaze as an accent flowing down the sides of one of his pots. “I put on just enough so it wouldn’t hit the bottom,” he remarks. “It was a period of glaze experimentation for me, learning about glazes and coming up with a distinct body of work.” His experiments created a feedback loop and “in the end, what I came up with looked a lot like the landscape from Kachemak Bay,” he says.

Later, O’Brien continued this experimentation as a student at Alfred University in New York, where he earned his bachelor of fine arts degree in 1996. There, he focused on special-effect and low-fire glazes. Since he had earned a living as a potter, O’Brien was advanced compared to many of his classmates; the experience allowed him to focus solely on glaze experimentation and three-dimensional glaze surfaces, he says.

“There were a lot of resources there,” O’Brien remembers. “I had MFA graduate students available to me. While I was there, I was able to take glaze chemistry classes in the ceramic engineering department. I would not have been able to do what I do now if I hadn’t gone to Alfred.”

It would take the artist another five years to fully develop the body of work and style he is known for today. By 2001, his pieces were recognizable, though more earth-toned than his current style. “They remained earth toned for about 10 years,” he says. “I gradually started making them brighter, now I can make them as bright as I possibly can.”

randyobrien.net