Influence and Inspiration

Various works by CM Russell

Writer Shannon Severson

Photographs Courtesy of Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West

[dropcap]K[/dropcap]nown as the “Father of Western Art,” Charles Marion Russell is primarily known for his powerfully detailed depictions of men in the West. Cowboys atop furiously bucking broncos, wranglers driving cattle over the rugged mountain terrain of Montana, strong Native American chiefs leading their men into battle, tribes skillfully tracking and hunting bison and the many adventures of Lewis and Clark all found their way into a visual narrative that largely shaped the ideas that we as Americans, and those in other countries, still hold today about the nature and character of the Old West.

But peek through the haze of dust and gunfire and you’ll find that Russell also depicted the powerful role that women played, not only in the landscape and culture of the West, but also in his own life and career.

“Charles M. Russell: The Women in His Life and Art” at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West (SMoW) through April 14, 2019 is a collection of 60 works in oil, watercolor, pen and ink, and bronze, along with a number of physical artifacts that span Russell’s career from 1890-1926. The works predominantly feature female figures and allow the audience an opportunity to view his celebrated artwork, life and career through a new, contemporary lens.

A series of educational and entertaining programming is tied to the exhibition, including scholarly lectures, a film series and even a performance by historical enactor, educator and storyteller, Mary Jane Bradbury.

This exhibit goes beyond “cowboys and Indians” and gives us a peek into how Russell saw and appreciated the women around him.

“The different perspectives of women and their roles in the West haven’t been very prominent,” says SMoW Assistant Museum Director of Collections, Exhibitions and Research, Dr. Tricia Loscher. “Russell’s work is seen as very masculinized with stories about the male and the American West. With this show, we see his sensitivities and all of his portrayals of women—not only how he portrayed them, but how they inspired him and really promoted his career.”

Even audiences who are new to Russell’s work will find much that is familiar. Hollywood borrowed heavily from his depictions. Everything from set design to story narratives were clearly lifted from the mind of this artist who was the consummate Westerner, cowboy, writer, conservationist, philosopher, historian, advocate of the Northern Plains Indians and the list goes on. He left behind both a visual and written account of his remarkable life and times.

As a young boy in St. Louis, Missouri, Russell’s cowboy dreams were kindled at the knee of his grandmother, Lucy Bent Russell, who regaled him with stories of the West and the adventures of her famous fur trader brothers who opened the Santa Fe Trail. His artistic mother, Mary Elizabeth Mead Russell, encouraged young Charlie to read adventure novels of westward expansion and to sketch and sculpt.

By the age of 16, Russell set out to live the cowboy life in Montana and never looked back. His sketches and watercolors of life on the range, both as a cowboy and during the time he spent living with the Blood Indians, a branch of the Blackfeet Nation, received little recognition early on.

All that changed when, at age 32, Russell married 18-year-old Nancy Cooper. He quickly went from being a working cowboy to a working artist at the urging, and under the business-savvy management of his young wife.

He lived to be just 62 years old, but he produced over 4,000 works in his short lifetime. He sold his paintings for $25 to $35; in 2005, his painting, “Piegans,” fetched $5.6 million at auction.

In fact, it is the work of a woman that inspired this exhibition. The late Ginger K. Renner, a Paradise Valley resident, published “Charlie Russell and the Ladies in His Life” in 1984.

“Ginger was a big influence in this museum and was a big inspiration for others to have this museum built, although she passed away before we opened in 2015,” says Loscher. “The curators, Joan Carpenter Troccoli and Emily Crawford Wilson, did a spin on her title for the show.”

Renner’s husband, Fred, grew up in Great Falls, Montana and sometimes visited Russell’s log cabin studio there to watch the artist at work. Both were premier Russell scholars and collectors of Russell’s life history and art. They were heavily involved in creating definitive catalogs of his work and in helping to establish SMoW and the C.M. Russell Museum in Great Falls.

“The Renners did a lot to forward not only Russell but Western art,” says Loscher. “In the whole scheme, they were huge promoters and philanthropists of Western art. Ginger sat on the boards of a lot of museums and was involved in various award programs promoting the West.”

Notable in the collection is the portrayal of Native American women performing the duties and responsibilities of their everyday lives, from moving camp to caring for children and mourning the dead.

“Keeoma” is one of a well-known series of paintings that depict a lounging Native American woman in the exotic tradition of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when it was common to paint women who existed outside of restricted Victorian-era norms. She rests against a teepee backrest.

“It’s a Native woman inside a teepee, but he’s drawing on the larger European sensibilities of exoticizing indigenous women,” says Loscher. “He’s playing up the exoticism of a time when it was often Middle Eastern women who were depicted, but he does it with an indigenous woman in Montana.”

The woman is surrounded by objects that give us a glimpse into her everyday life: a parfleche, which was a case made of rawhide, trade blankets, her beaded buckskin dress and the backrest she’s leaning against. Nearby, a real teepee backrest is displayed, as are saddles and clothing of the time.

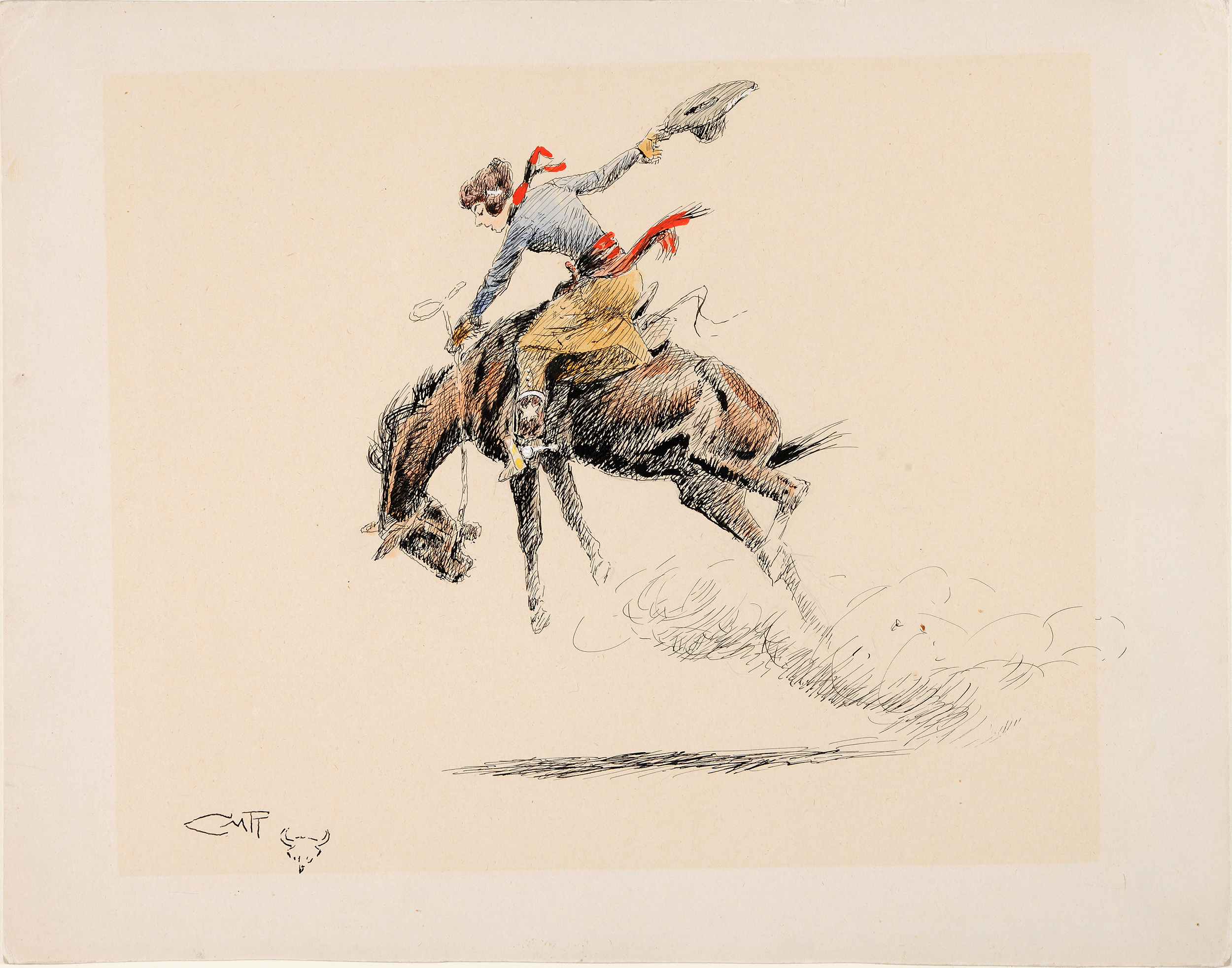

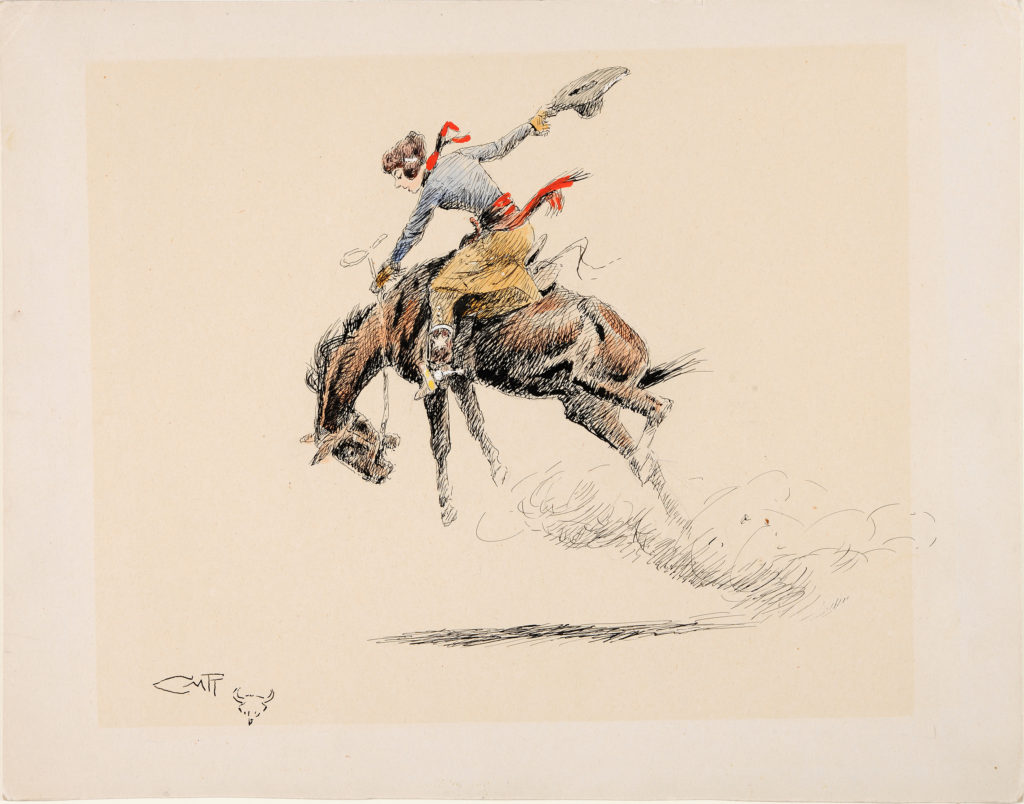

“Lady Buckeroo” is a rare depiction in watercolor, pen and ink of a woman skillfully riding a wild bronc, neck kerchief flying and hat held aloft. Strength and determination shows through in her expression.

Russell loathed the industrializing forces of westward expansion, and juxtaposed contemporary white women with impoverished Native Americans who were being displaced by development and urbanization in “The Last of His Race” and “Mothers Under the Skin.” They are painful, raw and real.

“Russell humanizes what different cultures were doing at the time,” says Loscher. “He really gives you a feeling of what it was like to be there, a sense of place, because he lived it. That’s why everything about his paintings—the objects, the animals, the people—are so vivid. It’s something to keep in mind that not only are the stories in all these works masterfully told, but they’re so beautifully rendered. He was able to capture everything so realistically.”

Also in the collection are examples of his collaboration with family friend and librarian, Josephine Trigg. The pair wrote hundreds of letters, which Russell would adorn with incredibly detailed, and often humorously themed, watercolors depicting life in the West during those days. Trigg composed poems in beautiful calligraphy that he would then illustrate. What resulted was a beautifully rendered and very personal historical narrative.

“Along with the theme of women,” says Loscher, “the groundbreaking aspect of this show is how it’s contextualizing his work in terms of the broader history of what is happening across the world at that time.”

scottsdalemuseumwest.org