Groundbreaking Garments

Writer Joseph J. Airdo // Photography Courtesy of Phoenix Art Museum

As Arizona’s temperatures begin to hit their 2021 peak, you have undoubtedly already reached for that swimsuit and taken a dip in a pool, lake or creek. If you are a woman, the chances of that swimsuit being a bikini may be somewhat high. But what is now common fashion was once considered scandalous.

The history of the swimsuit dates back to the 18th century. Prior to that, swimming was a mostly private activity — like bathing — so women did not have much of a need for any attire. The first swimsuits, known as bathing costumes or gowns, featured sleeves and were cut large as to float away from the body and obscure curves. Prioritizing coverage over practicality, they were most commonly made of wool but also occasionally came in canvas and flannel.

In the mid-1800s, bloomer swimsuits featured full skirts and wide legs that cinched — controversial in and of themselves due to their resemblance to pants, which were only worn by men at the time. Later bloomer swimsuits were cut higher on the leg and featured lighter fabric.

As sports gained popularity, early 20th-century swimmer Annette Kellerman debuted a one-piece, form-fitting suit that would increase her speed — and was arrested for wearing it. The design was eventually accepted and embellished with slimmer straps, ruffles and other fashionable elements.

Then, in 1946, Louis Réard designed a new swimsuit that he believed would be just as shocking as nuclear tests that had just occurred on the Bikini Atoll islands. Named after the islands, the bikini — made of stretchy nylon and latex — featured a daringly skimpy two-piece design with bright colors and high-cut shorts.

Scandal eventually made way to acceptance and finally popularity. The bikini is now widely available and worn in a variety of revealing styles that may have shocked even Réard.

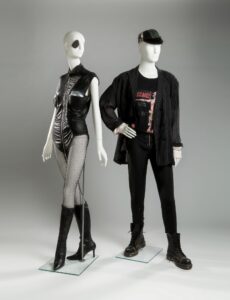

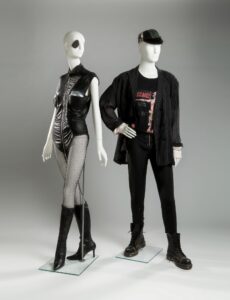

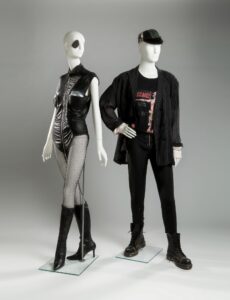

It is also just one groundbreaking garment among many featured in Phoenix Art Museum’s Fashion’s Subversives exhibition, which runs through Nov. 28. Spanning the 19th century through today, the exhibition showcases almost 40 examples of garments and accessories that broke from culturally accepted norms and forever changed popular fashion and the fashion industry.

“These designers thumbed their noses at the idea of conforming to traditional standards of popular fashion and were uninterested in anticipating the newest trends,” says Helen Jean, Phoenix Art Museum’s Jacquie Dorrance Curator of Fashion Design. “Instead, they sought to create something entirely new, something that people had never seen before, and this exhibition celebrates those moments of going against the grain in big and small ways to challenge long-held views of propriety, beauty and taste.”

Subverting Styles

Jean curated Fashion’s Subversive’s ensembles and accessories into five sections based on the subversive ideals they embody. The aforementioned bikini is featured in the Subverting Morality and Decency section.

In addition to the evolution of the swimsuit, the section looks at shortening hemlines in the 1920s, the rise of mini-skirts in the 1960s and the history of the slip dress — an underwear-as-outerwear design that, although popularized in the 1990s, began way back in the late 1700s.

Subverting Morality and Decency is only the tip of the iceberg though. Another one of Fashion’s Subversive’s sections is Subverting Gendered Dress.

“In this section, we look specifically at men’s suits as women have appropriated them into their wardrobe,” Jean says. “One of the most significant examples is Yves Saint Laurent’s 1967 smoking suit — the first tuxedo suit designed and engineered for a woman’s body. It is incredibly sleek in the way that it fits and hangs on the body but it carries all those notes of authority, power and success that we associate with the men’s suit.”

The smoking suit upset the balance of gendered dress and was therefore considered controversial at the time of its introduction.

Similarly, the advent of costume jewelry and Coco Chanel’s little black dress — both featured in the Subverting the Status Quo section — undermined the socioeconomic hierarchy of the industry by making versatile, stylish and expensive-looking clothing and accessories affordable for the masses in the 1920s.

“Up until that point, black garments were considered mourning dress,” Jean explains. “Introducing black as a chic and fashionable color in a silhouette and style allowed women of all economic statuses to look and feel sophisticated. And that was very upsetting to the fashion industry.”

Meanwhile, the Subverting the Social Order section features various accessories and garments that have been part of the fuel for change — such as the sash that women wore during the suffrage movement in the early 1900s and the pink hat that women wore during the 2017 Women’s March.

Finally, the Subverting Reality section of the exhibition features designers and movements that changed the shape of or created outlandish silhouettes that do not even follow the human form — such as the missile bra.

“The missile bra was this really bizarre fad or trend that lasted for a while in the 1950s and 1960s,” Jean explains. “It created this incredibly pointed, very artificial shape to the woman’s breasts. The human body does not do that naturally. That is just not how gravity works.”

Revolutionarily Revealing

In 1964, designer Rudi Gernreich — who is at the center of Phoenix Art Museum’s Fearless Fashion, a special exhibition that is complimentary to Fashion’s Subversives — brought the swimsuit full circle with the introduction of the monokini. Covering up only slightly more than the birthday suits women wore when swimming prior to the 18th century, the revolutionarily revealing topless swimsuit consisted of only a brief, close-fitting bottom and two straps.

Although today’s swimsuits are at least a bit more modest than that, it exists as proof that history is rich with examples of designers who bucked tradition and used their craft to challenge societal norms that limited self-expression.

“Fashion is important in life,” Jean says. “It is how we, of course, protect ourselves but it is also how we indicate who we are, where we are, what we are doing, where we are going and how we are feeling. Fashion is a pretty big expression of ourselves in the world and it relates to so many things.”

Jean adds that fashion collections in art museums are being taken more seriously now than ever before, with patrons eager to see, explore and consider the conversations surrounding it. She encourages Phoenix Art Museum patrons to always read the labels that accompany each item as they uncover many fascinating facts.

“One of the many delightful parts of this job is discovering these amazing little moments that have occurred in our artistic history and sharing those with the public,” Jean says. “Fashion’s Subversives looks at those designers and garments that broke the rules in big ways but also in small, subtle ways.

“Fashion is intended to cause controversy, to create a stir, to ignite conversation and to bring people together to consider things outside of what is normal to them. Fashion can change our opinions, challenge our beliefs and be a catalyst for change and for expanding our minds. Fashion is a way that we communicate and we have so much valuable information to share between our cultures and between each other.”