Writer Rebecca L. Rhoades // Photography by Loralei Lazurek

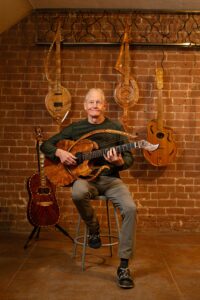

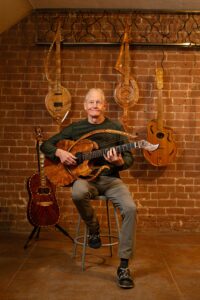

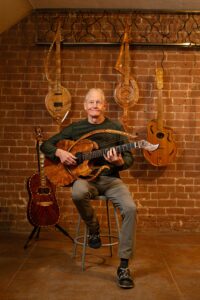

Brady Shreeve has always loved the acoustic guitar. But it wasn’t until his father-in-law mentioned the Roberto-Venn School of Luthiery that the Mesa native knew what he wanted to do with the rest of his life.

“I didn’t know that guitar making was a thing until then,” he recalls. “We were on a family trip, but as soon as I got home, I looked up the school, and classes started a month later. I quit my job, and I’ve been here ever since.”

Today, Shreeve serves as a workshop assistant. It’s the first step in what he hopes is a long career with the school.

“I came here and learned that it’s a very special place,” he says. “It’s a little hub of weirdos who all have a common love of guitar.”

It’s a sentiment and storyline that has been repeated over and over by students and instructors for almost 50 years.

Building a Legacy

The Roberto-Venn School of Luthiery was founded in 1975 by John Roberts, Robert Venn and William Eaton.

Roberts was a pilot for a lumber company who lived in Nicaragua. Throughout the ‘60s, he had been collecting exotic rosewood with the goal of building a yacht, but before he could accomplish his dreams, his wife developed eye problems. The couple decided to move to Phoenix, but Roberts kept the wood, shipping three boxcar loads by boat to New Orleans and then by rail to Arizona.

One day, while trying to sell some of the lumber, he bumped into a guitar maker who was impressed with its quality and suggested that Roberts use it to build guitars. Although he didn’t play, Roberts did have a fondness for woodworking, so he decided to give it a try. He was a natural. Eventually, he began teaching others how to do the same under the name Juan Roberto Guitar Works.

In 1973, Roberts befriended electric guitar maker Venn, and the pair decided to start an informal build-your-own-guitar workshop. Eaton, then a student at Arizona State University, met the duo during one of these courses.

“It took me about four months to build a guitar, and I thought that would be the end of my guitar-making career,” Eaton recalls, noting that he was headed to Stanford Business School.

But for one of his classes, he was required to develop a small business plan.

“I thought why not take Juan Roberto Guitar Works and make it into a school,” he adds.

Eaton presented his plan to Roberts and Venn, and they liked the idea. Upon graduation, Eaton returned to Phoenix, and the trio officially opened the Robert-Venn School of Luthiery.

“I didn’t put my name on it just out of reverence to John and Robert,” Eaton notes. “To this day, I keep the name. It’s a tradition.”

He also kept some of that original rosewood. He plans to use it to create 50th-anniversary guitars.

The school offers two main programs: the five-month-long (880-hour) flagship Guitar Making & Repair course and two advanced 10-week-long Guitar Repair courses. Both programs are full-immersion, hands-on learning. At the end of the five-month class, students will have created both an acoustic and an electric guitar, which they keep.

“Everything is pretty much done by hand,” says assistant director Bart Applewhite. “We don’t even do CNC work here.”

A bass player, Applewhite graduated from Roberto-Venn in 1993. After touring as a musician, he joined the staff full-time in the early 2000s.

“We teach fundamental hand skills, because you can always learn the computer programming part of it after you learn the fundamentals,” Applewhite adds.

More than 2,000 students have graduated from the school since it first opened its doors. Notable alumni include acoustic builders Jason Kostal and Ray Kraut, both of whom spent time with master luthier Ervin Somogyi; master builder Paul Waller; Joe Naylor of Reverend Guitars; Jason Lollar, one of the top pickup winders in the country; and the founder of PRS Guitars, Paul Reed Smith.

Inspiring Leadership

Like so many of his students, Eaton played in bands in high school.

“There’s something I loved about playing guitar, but I didn’t think I was good enough to be a professional musician,” he says. “I had no idea my life path would move in this direction.”

He recalls his days as a student at ASU. A business major with a pole-vaulting scholarship, he filled his days with studying and athletics.

“I would pull out the guitar at night just to relax,” he says. “That’s how I developed my style.”

But it was the skills he learned from Roberts and Venn that brought him worldwide acclaim — as both a musician and as a luthier.

Eaton is renowned for his one-of-a-kind multi-stringed instruments. These unique creations can have as many as 26 strings. Typical guitars have six strings. Each guitar is handcrafted from exotic woods, such as koa, rosewood and ebony, and many feature inlays of precious stones and shells.

Their unusual shapes are influenced by ornamental furnishings, insects, ancient lyres and Native American instruments. And the sound is more reminiscent of a sitar, zither, harpsichord or harp than it is a rock ’n’ roll ax.

“One of my guitars even looks like a harp,” Eaton points out.

Over the years, Eaton has recorded 16 albums; performed with orchestras and acclaimed artists, such as multi-Grammy-nominated, platinum-selling Navajo-Ute flutist R. Carlos Nakai; and received the prestigious Arizona Governor’s Arts Award. He also has been nominated for four Grammys, including Best Traditional Folk Album, Best Native American Music Album and Best New Age Album.

“William is an inspiration on so many levels,” Applewhite says. “He’s the glue that holds this school together. He’s a kind of Renaissance man, if you will. And we’re all fortunate to have him at the helm.”

Building Guitars, Building Careers

If there was one good thing that came out of the pandemic, it’s that many people took up playing musical instruments — with a majority picking up the acoustic guitar. And the past few years saw an astronomical spike in guitar sales. Retailers such as Guitar Center and Sweetwater saw 2020 sales increase by more than 50 percent over the previous year — and the demand is not slowing down.

“More guitars were sold during COVID than probably had been over the last 10 years,” says chief repair instructor Robert Mazzullo. “So they’re out there, and they’re all going to need to be fixed at some point.”

Mazzullo graduated from Roberto-Venn in 1995 and has been an instructor on and off since then. Most recently, he returned to the school in 2019 to teach the 10-week Guitar Repair course.

“Basically, I teach students to become guitar mechanics,” he says. “I want them to be able to walk out of here and open up a shop in their garage or go to work for somebody and make a viable living.”

The coursework opens up possibilities that many never knew existed.

“A lot of our students come here because they’re out there in the world trying to figure out how to get into this industry,” Applewhite says.

One such student is San Tan resident and military veteran Boushon Arnold.

“I was working at Intel, and I didn’t like what I was doing,” Arnold explains. “I had picked up the guitar about three years ago and really got into it. I just loved the way it was as an instrument. I was trying to figure out what I could with a guitar, and luthiery just happened to be something that popped up.”

Arnold hopes to work in repair after graduation.

Mark Allred also got his start at Roberto-Venn as a student in 2014. Now, the certified luthier helps teach some of the school’s specialty classes, including Tube Amp Design, French Polishing and Lap Steel. Ranging from two days to seven weekends, these avocational classes touch on fields related to luthiery and are aimed toward hobbyists.

“This school is one of those things that, if you’re in the industry, you know that it exists,” Allred says. “You can talk to 50 people at Gibson, and everyone seems to have gone through here. But as far as the rest of the Valley, it’s a hidden gem. I went through, built a couple of guitars, and now I’m hooked. This is the thing that I needed to be doing.”

Shreeve concurs.

“I have nothing but respect and admiration for the school, and I’m super proud to be a part of it. I don’t plan on going anywhere,” he says. “Come back in 20 years, and hopefully I’ll be right here doing the same thing. Maybe just with partial ownership.”

Comments by Admin