Writer Beth Duckett

Photography courtesy Jody and Susan Folwell

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]here there is clay, there is hope,” says artist Susan Folwell. Indeed, the award-winning potter from Santa Clara Pueblo, New Mexico, knows a thing or two about working with clay. She comes from a long line of successful artists whose influence on the world of Native American pottery remains unparalleled.

Her mother, Jody Folwell, revolutionized Native pottery in the 1970s with her avant-garde techniques, firings and designs, which continue to this day. Her grandmother is Rose Naranjo, the late Santa Clara potter and matriarch of a continuing dynasty of accomplished artists. Rose raised 10 children, eight of them born to her, and taught all of them how to work with clay.

You could say, then, that clay run s in Susan’s blood. Her earliest memory of dabbling in the art form was as a curious 6-year-old, when Susan asked her mother for some of the earthen material so she could create her own masterpiece.

“I made a squiggly little worm,” Susan recalls with a chuckle. “My mother pinched the nose on the worm. She said it gave it character.” She later sold the piece for $2.

“Character” is one word to describe Susan’s exquisite pots, jars, vases, bowls and canteens, which harbor designs inspired by pop culture, personal and world events, oftentimes with added depth or humor. What she shares with her mother Jody is a regard for storytelling, innovation and the use of both traditional and non-traditional surface techniques.

There is more to their ceramics than meets the eye, as their etchings reflect a plethora of designs and imagery that can captivate, inspire or prompt one to wonder: Is there a deeper meaning behind this?

Jody and Susan are “about the story and the message, and not reliant on simply the form and a perfectly polished exterior,” says Charles King of Scottsdale-based King Galleries on Marshall Way, which specializes in classic and contemporary Native art. “The fun of their work is often hidden in the detail, and the nuance, of how they present their subject matter.”

“I do send messages in my work, sometimes even just to myself,” says Susan, who grew up in Santa Clara Pueblo, the largest of New Mexico’s 19 pueblos, and currently lives in Taos, New Mexico. “I hide little things inside pots. It’s kind of neat to be able to look back on my own work and sometimes recognize that.”

To this day, Susan sees and remembers details about the many pieces she has created over the decades. Often, she can tell where she was living at the time of its creation and how that experience molded her career. Like the time she lived in a small Hispanic village with only 300 or 400 people.

“The view from my bedroom was a Spanish ramada that was still being used,” Susan recalls. “A lot of Hispanic culture and Catholicism rubbed off on me. There is a lot of that imagery in some of my older work.”

The word “satire” has been used to describe some of Jody’s work, which often reflects social commentary and innovative designs. The classic style of her pottery includes a fully polished surface and, at times, an asymmetrical mouth or rim.

Susan is known to imbue humorous or fun elements into her designs, such as in the “Wind Wagon” jar she made specifically for an exhibit in the Netherlands more than a decade ago.

The 10-by-12-inch jar boasts spirited etchings of red cars, gold horses and stars over a mountainous-looking backdrop. Susan broke the piece and laced it back with metal and glue, creating a look like a roadmap or staples. According to the King Galleries’ website, its theme is the evolution of Native American transport from horses to cars.

“I find humor really helps,” Susan says. “Sometimes it’s a really disturbing subject matter. It helps people to relate. It’s not so alarming.”

Another time, Susan found inspiration in a surprising place for her “Cry Baby” series. Susan was approaching deadline for the Santa Fe Indian Market and happened to view the iconic 1963 painting “Drowning Girl” by Roy Lichtenstein. “I related to it so much,” she says. “I was staying up late, tired, overworked, running up to a serious deadline. The woman drowning in the water, it tickled me and I was really there. I borrowed upon that image … adding humor to a stressful situation.”

In more recent works, Jody and Susan re-interpret classic paintings done by Taos artists through the eyes of their Native American subjects, King says. Their pieces range from funny to elegant and thoughtful. You can view the Taos works during a showing, “Peering Through Taos Light,” at King Galleries April 6.

July 1, 1915, six painters—Joseph Henry Sharp, Bert Phillips, Ernest Blumenschein, E. Irving Couse, Oscar Berninghaus, and Herbert Dunton — came together to form the Taos Society of Artists. All the original founders had visited Taos and were enchanted with the high desert, colorful skies, pine-dotted mountains and adobe-style architecture of the valley in north-central New Mexico. Six more members joined before the group disbanded in 1927, but their legacy continued on as Taos became an international artists’ enclave. Taos Art Museum at Fechin House estimates that there are currently more artists per capita living in Taos than any other city in the world.

Susan has a special connection to the late Taos artists. Her husband, Davison Koenig, is executive director and curator of the Couse-Sharpe Historic Site, which includes the home and studio of Couse and two studios of neighboring artist Sharp. Over the summer, the two helped organize an art show with the Couse Foundation. “To be able to view their works quite often now that I’ve moved to Taos has really given me an interesting perspective,” she says.

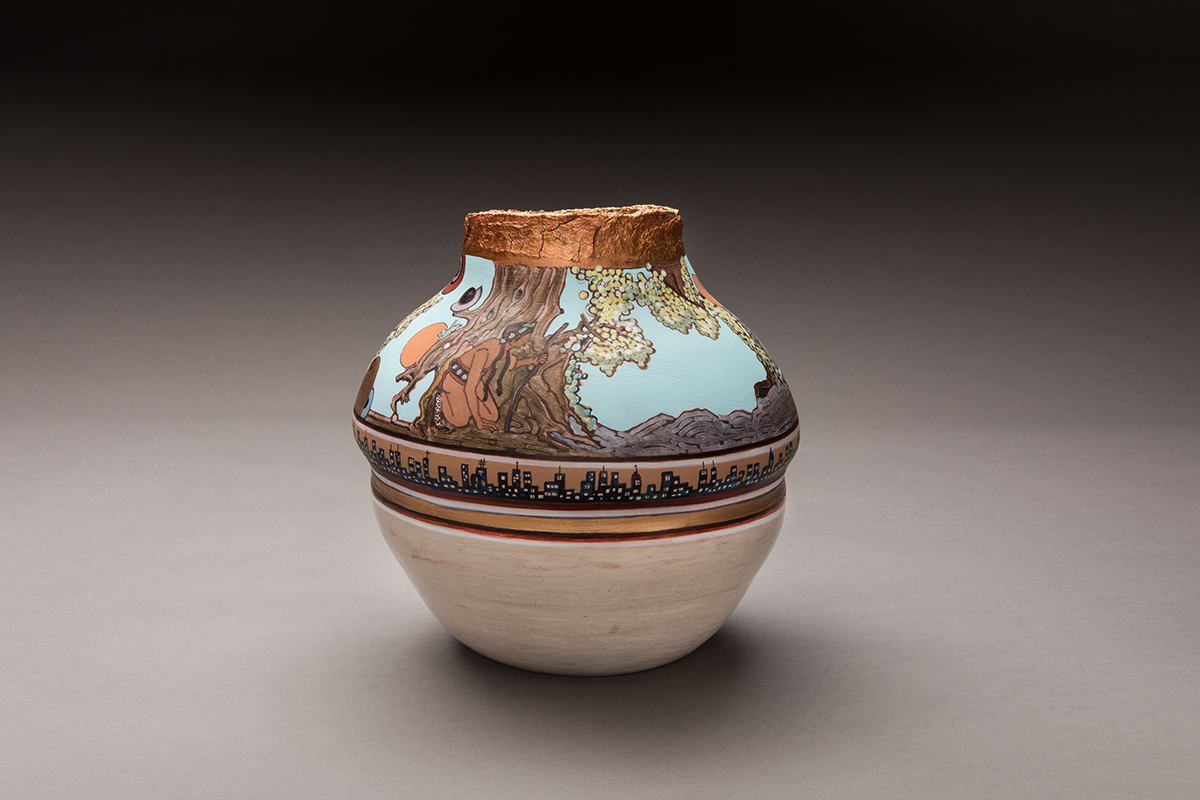

Susan created a jar, titled “Vanishing,” that uses imagery from Couse’s work. The piece shows a Native American man crouching and hunting. In the actual painting, you can see deer in the background, but Susan left it blank in her work. Instead, her backdrop is a sky blue color. Underneath the image is a skyline of New York City that is a reflection of “blending in with American culture, losing rituals, slowly losing the true Native American identity,” she remarks.

For Jody and Susan Folwell, their identities as Santa Clara artists, potters and family members remain constant as they explore and expand their oeuvre into new realms. Their works speak loudly for the future of Pueblo pottery, and art in general.

Peering Through Taos Light

4168 N. Marshall Way, Scottsdale

April 6

6 – 9 p.m., Free

480-481-0187

kinggalleries.com

520-275-9952

folwellkoenig.com

Comments by Admin