Writer Shannon Severson

Photography Courtesy of Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West

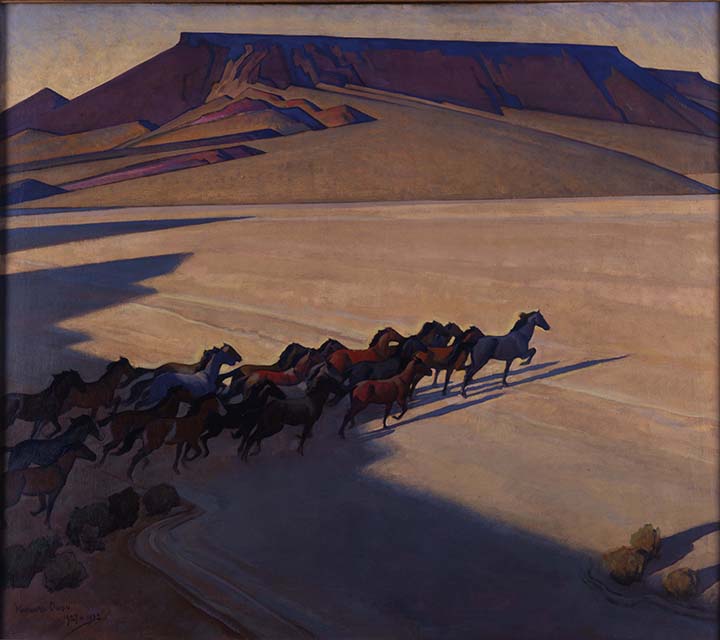

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]ven if you’ve never heard the name of artist Maynard Dixon (1875-1946), you’ve seen his work. Dixon’s original drawings heavily influenced architect Irving Morrow’s ultimate design of the Golden Gate Bridge. He even chose its distinctive color. In fact, Dixon recommended Morrow for the job.

This impactful tidbit is just one in the fascinating story of an artist whose life and work spanned the years that most shaped America and the world in the 20th century, and whose paths crossed with some of the most influential figures in the history of the American West.

Much of it is on display at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West’s Maynard Dixon’s American West, the world’s most comprehensive retrospective showcasing Dixon’s life and artistic career.

The exhibition is the first of its kind in Phoenix, with 250 works, including some of his most historically significant paintings: Cloud World, Earth Knower, Shapes of Fear and Kit Carson with Mountain Men.

“We’re honored to have received so many major Maynard Dixon works that are being seen together for the first time,” says Dr. Tricia Loscher, assistant director of collections, exhibitions and research at SMoW. “For Arizona and on an international level, for us, this is a watershed moment in the five-year history of the museum—not just the number, but the caliber of these paintings and drawings.

“It’s the largest retrospective to date of Maynard Dixon and the first major retrospectives showing ever in Arizona. We have so many iconic pieces.”

Part of what makes this remarkable exhibition so impactful is the deep well of information that defines Dixon’s place in both Western and American history. That context is courtesy of the museum’s partnership with Dr. Mark Sublette, who was Loscher’s co-curator for the exhibition.

Sublette is the owner of Tucson’s famed Medicine Man Gallery and Maynard Dixon Museum, and he is a dedicated scholar of Dixon. His 525-page masterpiece book, “Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along the Distant Mesa,” serves as a foundational companion piece to this astounding display.

“When I first moved to Tucson, someone came to sell me a Dixon painting,” says Sublette. “It was instantaneous. It was love at first sight.

“Over the last 25 years, I’ve assembled my museum collection in Tucson. I’ve bought and sold Dixons, too—many major, important paintings. It was time to bring some of those back home for this exhibit, and people were willing to loan them. We have studies that accompany larger, significant paintings that have never been shown together before.”

At the entrance to the exhibit, a life-size photo of Dixon and his third wife, artist Edith Hamlin, is the background for his actual easel. Along the wall is a detailed timeline of his life, punctuated by photographs and early works.

Visitors are invited into the world of a man with a love of the unspoiled landscapes of the West running through his veins and artistic talent that would take nearly every form during times of massive social and economic upheaval in the world.

“The great thing about Dixon was that he was so good about documenting places, events and time,” says Sublette. “As a biographer, it makes him easier to write about.”

At the very beginning of the exhibition is a small sketch of an elderly woman that started it all. As a teen growing up in Fresno, California, often stuck indoors due to crippling asthma, Dixon sent his sketchbook to his idol, Frederic Remington—and Remington wrote back.

In one corner of the page, a notation reads, “This is a good study,” in Remington’s own hand. It was 1891, and encouragement from Remington caused Dixon’s mother, Constance, to move him closer to San Francisco so he could receive formal training at California School of Design.

As it happened, Dixon was more boots, dust and great outdoors than cosmopolitan formality and enclosed classrooms. He didn’t stay in art school, preferring to study on his own, but he was always determined to make his living as an artist.

“There’s nothing else he could do or would do,” says Sublette. “He was a humble man, but the proudest thing he said about himself was that he made his entire life as an artist. It’s a hard thing to do.”

His first paying job was in illustration for a San Francisco newspaper, but being cooped up in the city didn’t suit his spirit.

Beginning in 1900, Dixon began a series of extended, months-long visits throughout the West and Mexico. Arizona and New Mexico were the first destinations in what would become a pattern of visiting and living among the people and environments he would go on to depict in a detailed manner true to life.

“Dixon was such a good ethnographer,” says Sublette. “When he painted Native Americans, he used the right clothing and their names. He meant his paintings to be the real essence of the people at that time, in that place, which was unusual for the era. He lived with the Hopi for five months. He would immerse himself in the culture to see what it meant to be a part of it.”

Sublette has collected letters and studied newspaper clippings of the many interviews Dixon gave over the years, studying the external influences that shaped his life and art. As the century turned, the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906, both world wars, the influenza pandemic of 1919 and the Great Depression all greatly impacted Dixon.

He wrote poetry, illustrated novels, created murals in public and private buildings, and documented the construction of Boulder (now Hoover) Dam; he worked, explored, struggled, triumphed and chronicled the times in art and letters.

Dixon was influenced by his relationships with prominent artists, authors and merchants of his time and by his three talented wives. His second wife, documentary photographer and photojournalist Dorothea Lange, was the most well-known. Her striking photographs placed a powerful spotlight on the suffering wrought by the Great Depression. Dixon’s Forgotten Man series was his venture into social commentary on the events of the time.

“I’ve said that Dixon was like the Forrest Gump of art,” says Sublette. “When you think about all the people he interacted with and knew who were historically important –– [journalist] George Lummis was a father figure to him, Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, Buffalo Bill, Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Lorenzo Hubble, who owned a crucial trading post on the Navajo reservation. He’s one of the few great Western artists who was actually born in the West.”

Dixon passed way in Tucson on November 13, 1946, just days after completing his final mural commission, a massive painting of the Grand Canyon for the Santa Fe Railroad’s Los Angeles ticket office. He had completed it while suffering terribly from his asthma, only able to work for a few hours each day.

While tragic, his death was emblematic of his drive to create and to communicate the natural beauty of the region that was part of his soul. It lives on in this exhibition.

Maynard Dixon’s American West

Through Aug. 2 | See website for hours | Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West | 3830 N. Marshall Way, Scottsdale

$15 Adults | $13 Seniors (65+) and Active Military | $8 Students (Full-time w/ID) and Children (6-17 years)

Members and Children 4 and Under, Free | Free on Thursdays (Through April) for Scottsdale residents with proof of residence

480-686-9539 | scottsdalemuseumwest.org

Comments by Admin