Writer Amanda Christmann

Photography by Carl Schultz

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n a quiet corner of Carefree, the knowing eyes of two bronze sentinels stand guard in front of Grace Renee Gallery. Remarkable for their artistic quality, the expressive faces of this equine pair are well-suited to their names: Power and the Passion.

Yet art imitates life. The true beauty of these majestic sculptures lies not in their obvious visual appeal, but in the stories behind the finer details.

In the early 1990s, artist J. Michael Wilson spent many months using bronze to create two larger-than-life horses that would eventually be installed in front of a then-new building in downtown Glendale, California. It was, and remains, the tallest building in the city, and his horses, called Power and the Passion, were meant to honor the past and inspire future generations.

Wilson had been creating commissioned work for several years, including work for Mattel Toys, Lloyds Bank, the 1984 Summer Olympic Games and University of Southern California. His bronze sculptures of both human and equine forms were striking, and he was in high demand when the Glendale developer called.

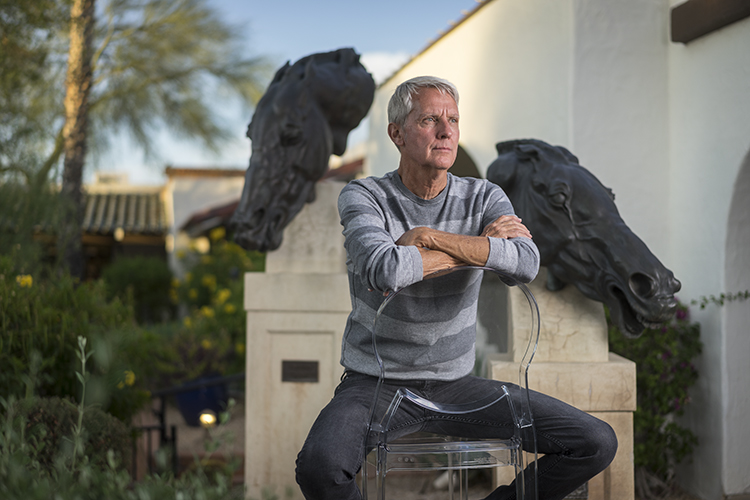

Thirty years later, Wilson isn’t in a hurry as he explained the story. The cadence of his carefully measured words is an expression in itself. We both settled comfortably into our chairs as he spoke.

“The whole thing behind Power and the Passion is …” he said, his words trailing off as he processed just where he wanted to begin. He took a quick but sizeable breath and continued, growing more animated as he spoke.

“As an artist, I see all of these sculptures in front of buildings, and I’ve always thought, ‘Why can’t you integrate the sculpture with the building somehow and have the two work together?’

“In my head, I saw this team of really powerful horses, and I thought, ‘Wow! Yeah! What if we have these two powerful horses working together?’ Then I started thinking about everyone in the building and how they would also be working together, and that was a great way of tying the two concepts together.”

He sat upright in his chair as he explained the idea that had bloomed in the corners of his mind so many years ago.

He’d imagined the two spirited horses bound by chains to the building, working in concert to pull it forward. He envisioned the strain in each muscle of their bodies as determination and raw power drove them onward. The building itself would become part of the artwork, with a portion pulled out as if moved by the horses’ might.

He built his story to a crescendo, then nearly half a lifetime of regret seeped in his voice.

“Everybody loved the idea except one person—the architect,” he said, flopping back in his chair.

Unwilling to change the lines he’d drawn, the architect had nixed the idea of incorporating the building into the artwork. Bound by his role as a commissioned artist, Wilson was forced to capitulate.

The developer seemed determined to carry the concept, through.

“He said, ‘That’s okay. We can still attach cables to the building and make it appear as if the horses are pulling it.”

Wilson spent countless hours creating the molds, then refining his work. His own desire for perfection—not for his own purposes, but to please his employers—often drove him to work through the night. He painstakingly shaped every muscle, vein and hair on the horses’ bodies, and he made indentations in the figures where the cables would fit for the final installation.

Before the molds were destroyed, Wilson recast only the heads of Power and the Passion and designed pedestals for them. After years of standing proud on a large local horse ranch, they are now looking for a new home at Grace Renee Gallery.

Like a parent sharing photos of their children, Wilson shares a picture of his bronze horses.

“The one that’s down, that’s Power; the one that’s up, that’s Passion. When I was making them, I often thought they could have been called ‘Agony and the Ecstasy,’ because those were better descriptions of what I was feeling.

“They are the largest pieces I had ever done, and it was quite an undertaking.”

On the day of the install, the horses were settled into their permanent home, save for the cables, which were to be installed the following morning.

“The developer said, ‘You know what? I think they look just fine without the cables on. Let’s leave the cables off.” Once again, Wilson had no authority to make his own artistic decisions.

“If you look closely, those horses have indentations on their muzzles where cables were going to go,” he explained.

“Now, I see that they are a metaphor. We all have invisible ties that keep us from doing things.”

Breaking the Chains

For a moment, we both remained quiet, gathering our thoughts. As fellow creatives, we understood the unspoken.

For artists, musicians, writers, photographers and others in our eclectic tribe, our work is often not entirely our own. Most of us want desperately to be untethered so that we can be free to express ourselves in our own unique way, yet we are bound by responsibilities, economics and expectations.

“It’s always a struggle for me to find a happy medium between what the person who is commissioning it wants and my own ideas,” Wilson said.

We commiserated on the fact that we often find ourselves viewing our work through the perspective of a real or imagined audience. Our idea of “good” work has less to do with our own self-expression than it does about gaining approval from others.

For Wilson, change is in the air.

“I am 66 years old, and I’ve been doing this for 37 years. Now that I’m getting a little older and have some work behind me, I’m feeling a little more freedom to explore who I am as an artist,” he said.

“I just keep telling myself that I’m not sculpting for an audience anymore. I’m sculpting for myself. It doesn’t matter if no one understands it; it’s something I have to do for myself.”

Recently, he has left old habits and comfortable spaces behind and began a new series of pieces. For starters, he’s set aside his oil-based clay.

“I tend to overwork my pieces,” he said. “With oil-based clay, I can take as long as I wanted because it won’t dry out on me. Last December, I thought, ‘What would happen if I use something that has a time limit on it?’”

He shifted his medium to plaster, and for the first time in his career, began focusing on small-scale figures.

“Every day has been revealing new stuff to me,” he said. “It’s really exciting—kind of a departure from what I normally do with my work.

“I’ve been feeling this change coming on for close to 10 years, but I’ve been so afraid to allow myself to do it,” he said. “People expect your work to look like the other pieces you do.”

Passion lights his eyes from the inside as he speaks of his latest work.

“I’m just seeing so much beauty in these simple forms,” he told me. “At the core of it is the freedom to create anything I want and know that it’s just as legitimate as anything else I’ve done, even if it’s just for me.”

And so Wilson is emerging, unbound and untethered. With his release has come not only an evolution in his work, but in his thoughts on the legacy he would someday like to leave.

“I was thinking about it as I was working this week,” he said with a thoughtful inflection. “It’s kind of a like an entry in a journal. What I do today is my entry in today’s journal. It’s, ‘This is who Michael was today.’

“It doesn’t mean it’s who I will be tomorrow or who I was yesterday. It’s just who I am today, and that’s good enough.

“I want to be authentic. I want people to know who I was, not who I was made to be.”

We both smile knowingly as we relax into our cushions.

“See what happens when you ask me about art,” Wilson says with a grin. “I just go on and on.”

Comments by Admin