Cowboys Don’t Do Lunch

Writer Amanda Christmann

Photographer Herb Cohe

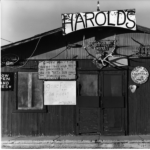

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]riving through downtown Cave Creek, it is not difficult to imagine the town’s early days. Rustic establishments Harold’s Corral, Buffalo Chip Saloon and Las Tiendas Plaza still hold the shadows of a bygone era when dusty cowboys and miners’ mules traveled this once-isolated stretch of dirt.

Cave Creek has always been home to tenacious folks whose gritty ingenuity got them through. From Native Americans who coaxed seeds to grow and water to rise from the parched earth, to miners who hitched their horses and dreams to mesquites, building adobes among rattlesnakes and sage, there has always been something special about the land and the people who choose to live on it.

This place seems to draw those who are not interested in living life by the rules. Cave Creek has always been home to the dreamers, the misfits, the outlaws and the eccentric.

In the 1970s, Cave Creek was an outpost of sorts to cowboys, bikers, artists and hippies. People with names like “Lead Pipe” and “OK Charlie” were regular faces at the post office, at Harold’s Cave Creek Corral and at the American Legion, three of the most social spots along the trail.

Long-time resident and filmmaker/producer Suzanne Johnson remembers those days well. “It really was ‘live and let live,’” she says with a nearly tangible wave of nostalgia in her voice.

“Everyone knew everyone else, and we all got along. The thing that united all of us is that we didn’t like change. We didn’t like the sprawl that was happening around us, and the last thing any of us wanted was to be part of the suburbs.”

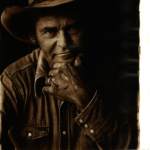

Among the characters was a good-humored, thoughtful man named Herb Cohen. Herb was a New Yorker, and he looked every bit the part. He had once been a minor league baseball pitcher with aspirations of going pro before the Army changed his plans and drafted him to fight in Korea. In the 1960s, he’d worked as an accountant, then opened his own East Coast manufacturing business.

Herb and his first wife Diana had taken to traveling the U.S. when they could, particularly to the desert Southwest. On one particular solo trip, he got lost on a desolate road north of Phoenix. As he drove, he eyed a for sale sign that read, “5-1/2 acres close to heaven.” A short time later, that acreage was theirs—in a new planned community called Carefree.

For years, the Cohens visited during holidays and vacations, toting along their twin boys Bruce and Stephen, and daughter Meryl. When the boys enrolled at the University of Arizona, the couple relocated here permanently in 1975, though he still commuted to his New York business regularly.

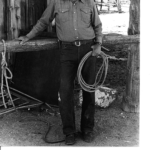

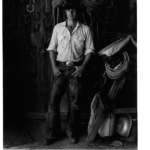

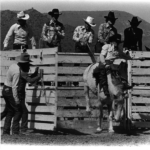

Herb’s favorite pastime was photography, a hobby that grew as he got to know the colorful regulars on the other side of Black Mountain. In particular, he was enamored by cowboys in saddle-worn jeans and dusty, weathered hats, and the affable Navajos just west of his tidy upscale community.

Everywhere he went, he carried his camera over his shoulder, which, at the time, was a sizeable haul. He connected with people and shared smiles and humor while his shutter clicked away. Always exacting, he focused on light and shadows, form and composition of his photographs. He had a natural gift for precision and a knack of capturing not only the subject, but for telling their story in pictures.

Though Herb had notable skill and passion for photography, he had no desire to become a professional photographer. To him, photography was an outlet of creativity; anything more would have turned it into something different—something less satisfying.

Out of pure love for the art, Herb snapped hundreds of photos or more of local personalities, preserving most of them as negatives in his own personal collection.

In doing so, he documented more than just the people—he captured a moment in time when smiles and cowboys were both genuine, and when the character of a man could be summed up by a handshake.

As long-time Creekers will tell you, it’s no longer the same. “Gosh it sure was interesting in those days, and it’s all gone now,” explains Suzanne.

Despite Cave Creek’s plucky determination to separate itself from suburban sprawl, change still seeped into the cracks of its arid foundation. Cave Creek incorporated in 1986, and for better or for worse, progress has left its mark.

Subdivisions sprung up. Tourism dollars began to fuel the local economy. Even bikers and cowboys weekend warriors with day jobs as lawyers or managers. For long-timers who lived in Cave Creek during that magical 70s era, it can feel a bit contrived.

“It was the past, and what we had is something that no longer exists,” explained Suzanne.

However, it was not all lost. A few years ago, a few pictures from Herb’s photography collection showed up on the walls of the Foothills Library , and with it came memories of long-gone familiar faces and places from before suburbia crept into Cave Creek.

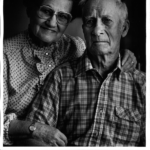

Gene Garrison, who had been one of Herb’s friends, kept track of some of his collection following his death in 2003. She authored a book in 2006 called, “There’s Something About Cave Creek: It’s the People.” She and Suzanne, a filmmaker/producer who owns Gnosis Media decided to salvage Herb’s unique legacy.

The two women teamed with Arizona Highways photographer Jerry Sieve and then-museum director Evelyn Johnson. They also contacted Herb’s children and widow, Anne, to obtain their blessing and input before pursuing development of a 160-page coffee table book called “Cowboys Don’t Do Lunch: The Photographs of Herb Cohen.” The book, in production now, is full of Herb’s photography and the colorful stories and memories they bring to life.

“This book is intentionally about the pictures,” Suzanne said of the book, available now in pre-sale. “They capture everything we wanted to say.”

But it’s not just pictures “Cowboys Don’t Do Lunch: The Photographs of Herb Cohen” is preserving; it’s a chronicle of our little corner of the world as seen through one man’s eyes—a man with adept ability to look through a lens and capture the soul of a town.

If you stand quietly among the wormwoods and brittlebush, you can almost hear the anxious nickering of a horse, the lispy echo of desert cicadas and the soft footfalls of worn leather boots on the limey desert ground. It’s all history, as they say—paved over in the name of progress, and blowing away in the breezes of time.

Like the roots of the mesquite, plunging deep into the soil, we are all integrally connected to each other through the roots of history. It’s through projects like this that our narrative, and who we are as this beautiful Sonoran community, will continue to be remembered, defined and honored.

Buy The Book:

Cowboys Don’t Do Lunch: The Photographs of Herb Cohen Presale

$50, including shipping and handling

For $150, in addition to the book, select one of three 16×20 matted, 8×10 gelatin Cohen photographs, custom created by Sieve.

Book to be released spring 2018.

480-488-2691