Writer Amanda Christmann

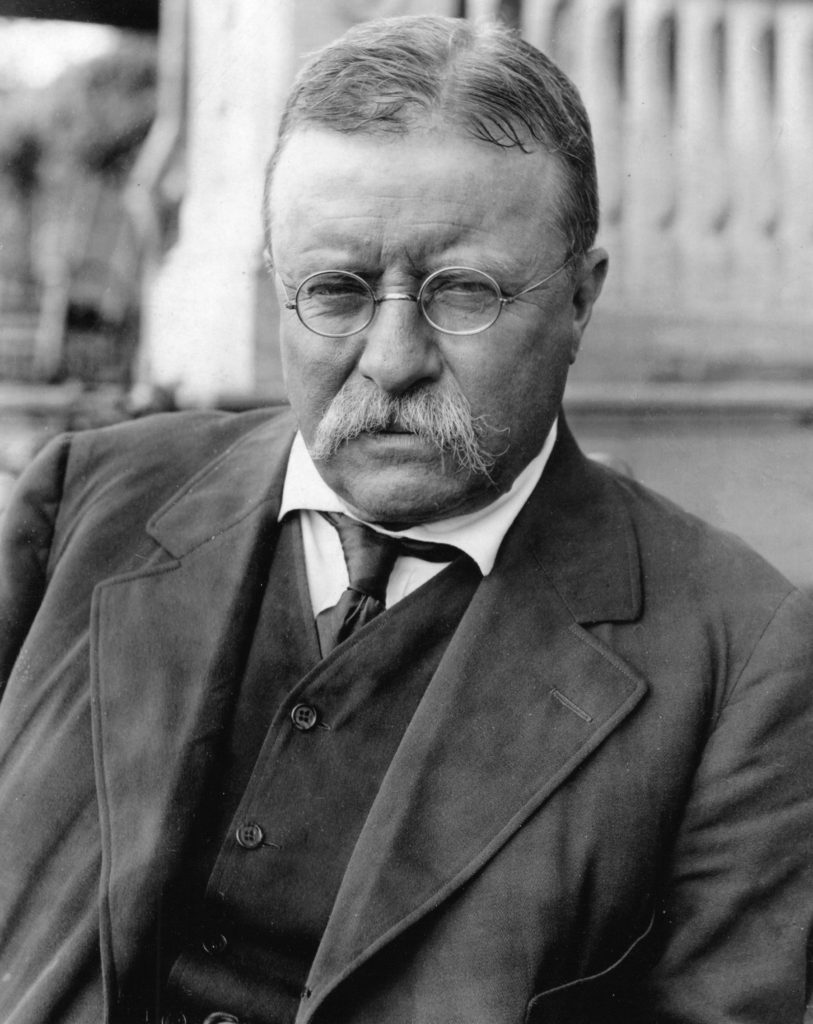

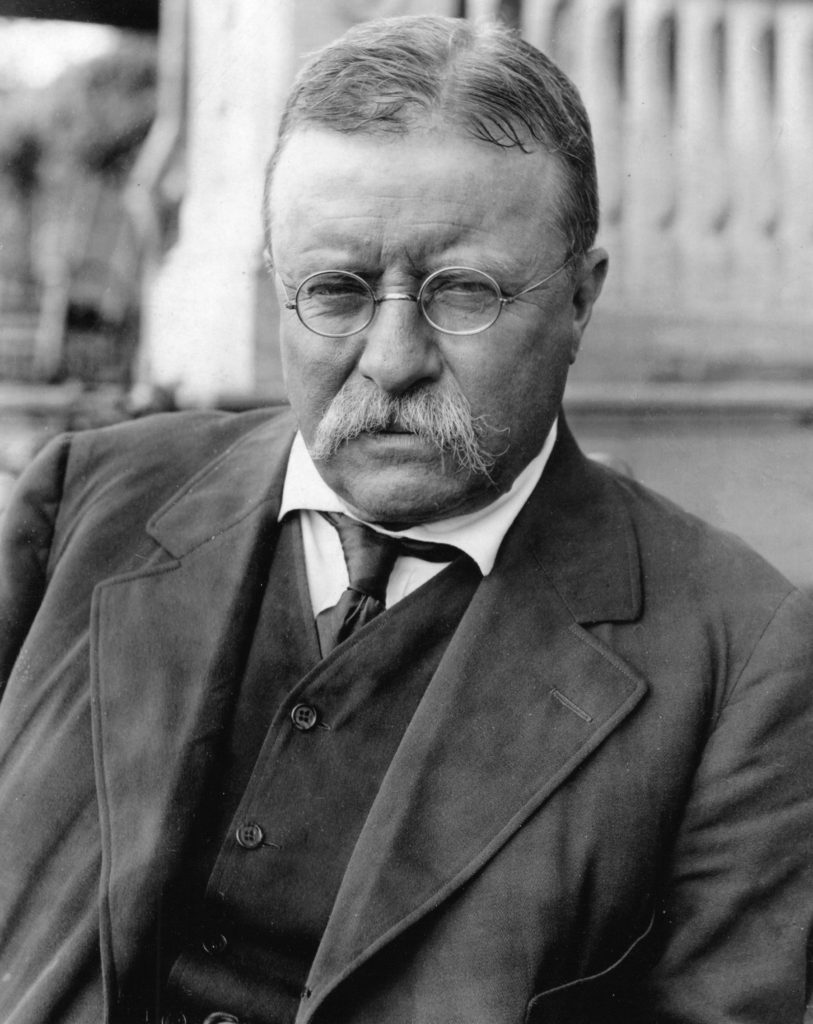

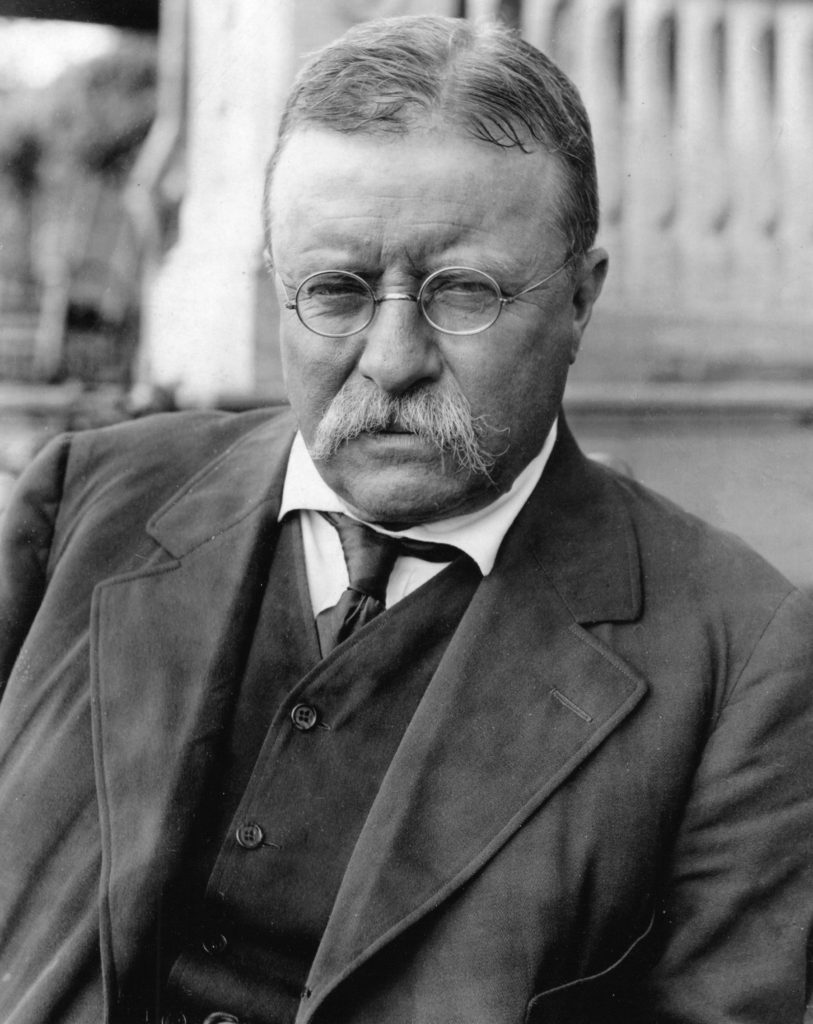

Photography Courtesy of Michael F. Blake

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ften larger than life, Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most beloved American presidents to have occupied the Oval Office—and for good reason.

Roosevelt overcame childhood illness to take public office at the age of 23 and quickly climbed the ladder of influence within his political circles.

When the Spanish American War broke out, he left a comfortable position as Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Navy to begin the First U.S. Volunteer Cavalry, famously known as the Rough Riders. He led troops into the Battle of San Juan and returned home a hero.

His first term as President was serendipitous—he was sworn into office when President McKinley was assassinated—but his second term was earned on his own merit. America fell in love with his dedication to preserving the land, for his compassion for the common man, and for his passion for our country.

The world will likely never see another Theodore Roosevelt in office, but if Michael F. Blake has his way, Roosevelt’s spirit and ideals—and even his spectacles and walrus mustache—won’t be forgotten.

This child actor-turned Emmy-winning make-up artist may seem an unlikely candidate for such a remarkable role, but it takes only one look at him in costume to be convinced.

Blake is a doppelganger of the venerated president—and it’s not only Blake’s looks that have contributed to his twin persona. As he tours the country appearing at events and in the media—including a special appearance in May at the Grand Canyon’s centennial celebration, his words, actions and perspectives seem to continue to mirror those of Theodore Roosevelt.

For Blake, it’s been a natural progression.

Blake grew up in Los Angeles, the son of well-known character actor Larry J. Blake, who, among other notable shows, appeared in several Westerns and ranch-based shows like High Noon, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and Gunsmoke.

When he was two, young Michael began his own career in acting, appearing in multiple commercials as well as “The Lucy Show,” “Bonanza,” “The Munsters,” “Marcus Welby, MD,” “Kung Fu,” “The Red Skelton Show” and “Bonanza.”

Perhaps seeing his father in those roles and taking part in a few himself developed Blake’s own passion for Western ideals.

“I was a cowboy-crazy kid when I was around 7 years old,” Blake says. “Nothing has changed except the price of the toys I have now,” he adds with a laugh.

“My parents got me a photo book of presidents at about that time. I knew about Washington and was somewhat interested in Lincoln because of my growing interest in the Civil War.

“Looking through that book, I became really frustrated. All of these presidents were in top hats and frock coats, and not a single one was on a horse.

“I jokingly say now that I turned the page and the heavens opened up—there was a picture of Theodore with a horse in Manitou in the Badlands of North Dakota. On the next page was a photo of him with his Rough Riders at San Juan Hill. From that moment on, he became my favorite president.”

As Blake got older, he remained intrigued by Roosevelt.

“I started reading more about him and thought, ‘This guy is really something.’ I admired him for speaking what he felt, doing what was right, and not being a mealy-mouthed politician. I admired him for being a real man and doing what he believed in. He didn’t back down.

“The more I read, the more I was and am amazed by him. What you saw was what he was. He didn’t wear cowboy hats to get votes.

“Even though he was a seventh-generation Roosevelt from New York, he connected to people of the West. He talked their language. A lot of that was him being himself, but also, a lot of that came from things he learned from his time in the West.

“If he talked to cowboys about a stampede, it’s because he knew what they were talking about. He had that authenticity about him that made people gravitate toward him.”

At the age of 21, Blake traded life in front of the camera for life behind the set when he became one of the youngest makeup artists in Hollywood. He built a lucrative career for himself, creating looks for characters in “Happy Days,” “Magnum P.I.,” “Westworld,” “X-Men: First Class,” “Spider-Man 3,” and “Independence Day,” among others. In 1999, he won his first Emmy for his work on “Buffy, the Vampire Slayer,” then earned his second for “Key & Peele” in 2016.

He penned several books, including three biographical novels about silent film star Lon Chaney, and Western-themed informative books, “Code of Honor: The Making of High Noon,” “Shane,” “The Searchers” and “Hollywood and the O.K. Corral.” Blake has also written for True West, Round-Up, American Cinematographer, Performing Arts, the Los Angeles Times, and Chicago Tribune.

He has appeared in a number of small features and received Western Writers of America’s Stirrup Award in 2017 for his article on the making of John Ford’s “The Searchers.”

Despite his successful career—and possibly because of it—Blake’s admiration for Theodore Roosevelt never waned. This year, he released his sixth book, “The Cowboy President: The American West and the Making of Theodore Roosevelt.”

The book details Roosevelt’s time in the Western Dakota Territory, then referred to as the West, where he went on a pilgrimage of sorts following the deaths of his wife and mother, who died on the same day in 1884.

“The Dakota Territory transformed Roosevelt into the man who is etched onto Mount Rushmore, a man who is still rated as one of the top five Presidents in American history,” Blake said. “The land, the people and the Western code of honor had an enormous impact on Theodore and influenced him in his later years.

“Theodore became one of the greatest environmental warriors our country has ever known, and fought hard and successfully for workers’ rights, just to name a couple of his accomplishments.

“People say we ‘conquered’ the West. That’s not true. We never conquer the West. You have to live on Mother Nature’s terms and whatever she hands you. For Theodore, he loved the challenge.

“Within a couple of days after he arrived following the deaths of his mother and wife, he went out to his ranch, saddled up and wanted to see if he could live in the West by himself—and he did.”

The West changed Roosevelt in other ways, too.

“People have a different way of being. Your word was your bond, and a handshake was just as good as a legal document. They are self-sufficient, and they had to do everything for themselves. It was a sink or swim mentality.

“Theodore owned a cattle ranch, and while he was doing a spring roundup, there were two stampedes—one at night. When he finally got back to camp, he slept until four in the morning when he had to saddle back up again. It was hard work, but he loved that stuff.”

That kind of practical gumption made for good presidential material, and it also shaped his thoughts on the environment.

“Back in the 1880s, people told him that the buffalo and forests were unlimited. He got out there and saw that we don’t have unlimited resources. By the time he became president, over half of our virgin forests were gone. He championed their preservation and sponsored efforts to preserve the land.”

“Back then, people shot game from trains. He realized that there wasn’t an endless supply of game either. He formed the Boone and Crockett Club because he wanted to preserve big game. In 1884, he pushed Congress to pass the Yellowstone Act, which gave them power to protect Yellowstone. He went after the mining and timber companies and forced them to be more responsible.”

Roosevelt was largely responsible for the creation of 230 million acres of preserved land, including creation of eight national parks and expansion of 150 national forests;18 national monuments; and 51 bird sanctuaries.

Like Blake, Roosevelt was also a voracious reader and prolific writer.

“One historian said that he probably had what would describe now as attention deficit disorder. He wrote 37 books, and he could read two books in a week. When he went after boat thieves, he went down the river reading Anna Karenina. He read War and Peace in French.

Roosevelt, Blake says, was a man of the people.

“He stood up for the people. He had tremendous foresight about what to do for this country, way in advance of things that would later happen. In 1910, when he went to Europe to collect the Pulitzer Peace Prize that it was just a matter of time before the U.S. would be in military conflict with Germany and Japan.

“He did what he thought was right for the people,” Blake adds. “He didn’t pay attention to the party line … I think that’s one of the reasons he is constantly rated at the top of all of the presidents, because he did what he had to do because it was the right thing to do.

“What he did in 60 years of his life is just amazing.”

Having the opportunity to educate today’s generations about one of our most remarkable presidents has been a gift for Blake.

“I still pinch myself,” he says.

Comments by Admin