Arizona Native Tribes

Writer Grace Hill

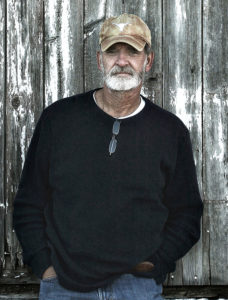

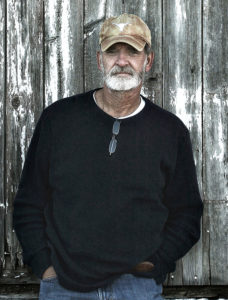

Photographers Scott Baxter

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s the sixth largest state, totaling 113,998 square miles, Arizona provides an extensive terrain to explore and admire. However, the land’s richness comes from more than the juxtaposition of desert and mountain landscapes. It also exists in the people of the land – the native tribes of Arizona.

Tribe Diversity

Arizona is home to one of the largest native tribe populations in the country. Currently, 22 tribes are federally recognized throughout the state. Two of the largest reservations in the United States can be found in Arizona: the Navajo Nation, located across Arizona, New Mexico and Utah, and the Tohono O’odham Nation, located in south central Arizona.

Celebrations

With so many native cultures located in Arizona, people living in or visiting here have countless opportunities to observe the non-religious ceremonies performed by different tribes. One traditional gathering, often called a pow wow, brings members of tribes together for a time of dancing and singing, enjoying friendships new and old, and preserving their heritage and culture. Non-tribal guests are sometimes invited to experience these pow wows first-hand. This opportunity allows for a deeper understanding and appreciation.

Art

Throughout history, native peoples have been regular contributors to the world of art. They have created and continue to create beautiful and intricate pieces of pottery, paintings, wood carvings, basket weavings and much more. Often, these pieces of art come from a place of tradition, worship and daily life. A common theme reflected in their art is an appreciation and understanding of the natural world, and because of this they frequently incorporate colors, elements and images found in nature.

Historical Sites

Since many native tribes of Arizona have lived here long before Arizona even had a name, the state features amazing historical sites. In northern Arizona, the Wupatki National Monument preserves Citadel and Wupatki pueblos. The Palatki and Honanki sites feature cliff dwellings in the red rocks near Sedona. And the Tuzigoot National Monument, located just north of Cottonwood, preserves a 2- to 3-story pueblo ruin. These are just a few of the many monuments and ruins scattered across Arizona.

To understand the history of Arizona, one must also understand the history, diversity and complexity of the native people who have lived here for many generations. However, access to any aspect of their life should be done with respect and gratitude. What may seem like “normal” behaviors by non-tribal members, might offend a Native American. Coming to them with a desire to openly learn the culture will ensure that all involved will leave with a greater appreciation for one another.

Hometown: Hartford, Connecticut

Current: Paradise Valley; Arizona resident since 1982

Photography experience: Self-employed professional photographer since 1986. Experience in commercial, editorial and corporate photography. Last five years focusing on fine art photography. Regular contributor to Arizona Highways with work featured in The New York Times; Cowboys & Indians; American Cowboy; Western Horseman; and Men’s Journal. One of his works is part of the permanent collection at Phoenix Art Museum. His book, “100 Years 100 Ranchers,” is available for purchase on his website.

Experience photographing native tribes: “Just starting at it. I’m kind of known more for my Western work of ranchers and cowboys, but in 2013 Arizona Highways had me photograph a cover based on cowboys and Indians. They brought in a gentleman named Jones Benally, who’s very well-known. He’s a very famous hoop dancer and Navajo medicine man. I then met his family and subsequently did some photography of him and his son. I’ve been working with them for a few years now. That’s where I kind of set out.”

Thoughts on capturing the essence of the human spirit in a photo: “I do things like talk to them about what is important to them, and places that are important. I kind of allow the subject to take me to those places, so to speak. It allows me to attach some sort of reverence to the photograph, not just for myself, but more importantly for the subject. When you are trying to get somebody to really let their guard down, it’s kind of a little bit of a dance you have to do with the subject. It’s easier if you work with them instead of directing them. To be patient. There’s a moment there that you know is correct.”