Writer Joseph J. Airdo

Photography Courtesy of JPB Publishing

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]magine walking underneath a working railroad bridge to find an 1890s world in which all of the wonders of the Old West surround you. To your left, people are panning for gold. To your right, they are exploring an abandoned mine. Straight ahead, there are shootouts between cowboys and Native Americans.

In the blink of an eye, that 1890s world is gone. In its place are Salt River Project corporate offices.

What was once an Old West theme park that invited visitors of all ages to play around in Arizona’s colorful history is now just another reminder of modern life.

Legend City was conceptualized and built by artist and advertising agency owner Louis E. Crandall in 1963. Like many entrepreneurs of the time, the then-33-year-old Crandall was fascinated by Disneyland in Anaheim, Calif. and aspired to replicate its success in Phoenix.

Of course, amusement parks had been around long before that. In 1895, Sea Lion Park at Coney Island in Brooklyn, New York paved the way for the popular trend of enclosed entertainment areas. Arizona State University emeritus history professor Dr. Philip VanderMeer says that the success of Sea Lion Park prompted the development of other amusement parks all across the country during the first half of the 20th century.

“Amusement parks were often built in association with streetcar developers who would run their streetcars out there as a way of getting double the money,” explains Dr. VanderMeer, who wrote about Legend City in his book “Phoenix Rising.”

Walt Disney then had the idea to expand upon the amusement park concept by focusing on a specific theme. In 1955, he opened Disneyland, incorporating elements of fantasy into his rides and attractions. Others hopped onboard the idea, including Six Flags founder Angus G. Wynne, hoping to introduce equally successful theme parks in other cities around the U.S.

Crandall mined Arizona’s roots for his version, incorporating an Old West theme into his 87-acre Legend City theme park near Papago Park off Van Buren Street on the border of Phoenix and Tempe. The Phoenix Zoo was under construction on an adjacent plot of land at the time and opened just a few months after Legend City.

The theme park opened to rave reviews June 29, 1963. Tickets, which included admission and access to all rides, cost $3 for adults and $2.25 for children. Vonda Kay Van Dyke, Sandy Gibbons, Dolan Ellis, Mike Condello, Hub Kapp and Wallace and Ladmo performed at the park’s Coca-Cola Golden Palace Saloon on a regular basis, while Kap’s Penny Arcade kept kids occupied for hours at a time.

Disneyland in the Desert

John Bueker moved to Phoenix with his family when he was 5 years old in July 1963, roughly one week after Legend City opened its gates. He was fortunate enough to visit the theme park for the first time later that summer and saw all of his wildest Western dreams become a reality right before his very eyes.

“Going to Legend City was a big deal,” Bueker says. “It was our Disneyland. We lived on the west side of Phoenix so traveling to Legend City was a long journey. We did not have freeways back then, so it was a very significant event. It was a big part of being a kid in Phoenix in the 60s and 70s.”

Bueker estimates that he only visited Legend City about five times, much to his dismay both then and now. However, the experiences he had there with his family left quite an impression on him—so much so that he created Legend-City.com, a website that keeps the memory of the theme park alive through pictures, memorabilia and even audio and video recordings.

“The Lost Dutchman Mine ride was my favorite [attraction],” says Bueker, noting that Crandall was inspired to create the ride by a similar one at Frontier Village—another now-defunct theme park in San Jose, Calif. “The one at Legend City was much nicer, though, and a lot more imaginative. It was one of the only original attractions that survived the full 20-year life of Legend City.”

In the Lost Dutchman Mine ride, park visitors boarded a mine car and traveled through a series of spooky and humorous scenes inside the supposedly haunted mineshafts of the Superstition Mountains before emerging into a small enclosed graveyard.

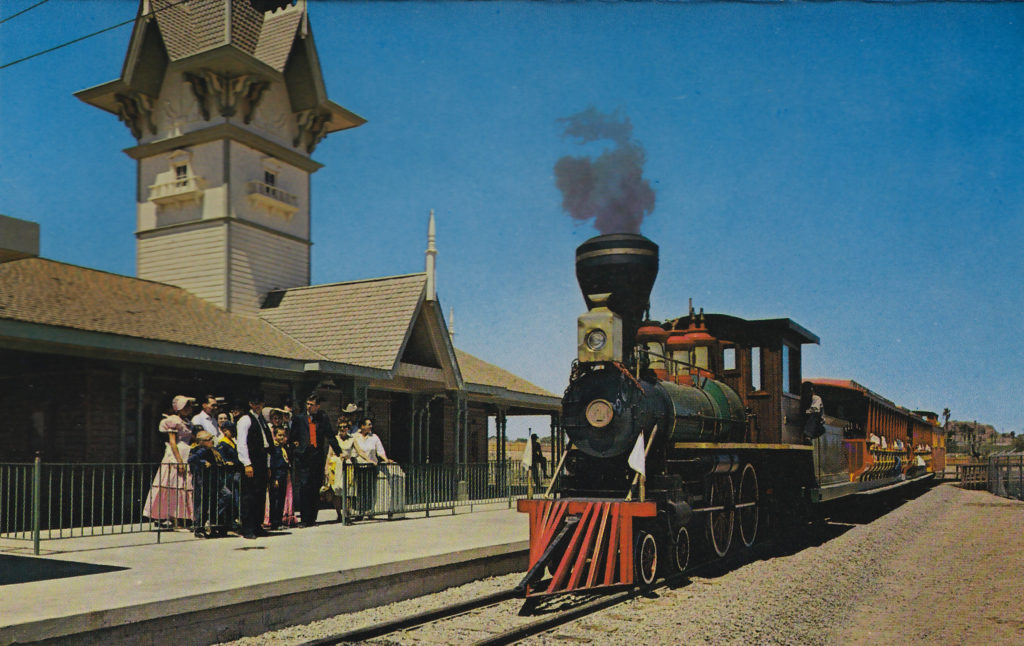

Another distinctive attraction at Legend City was the Iron Horse—a train that, powered by a replica 1860s steam engine locomotive, traversed the Legend City Railroad along the southern edge of the theme park. To fully embrace the park’s Western concept and to set the ride apart from a similar one at Disneyland, Crandall incorporated a clumsy robbery attempt by desperados into the attraction.

However, Legend City’s most ambitious attraction was River of Legends—a river ride, later renamed Cochise’s Stronghold, on which park visitors encountered Native American attacks, an earthquake and even dinosaurs. Many of the ride’s scenes were loosely based on actual places in southeastern Arizona such as the San Simon River, Fort Bowie and Apache Pass.

“They spent a lot of money building the river ride,” says Bueker, who also wrote a book about the theme park in 2014—one year after the 50th anniversary of Legend City’s grand opening. “Louis Crandall wanted to bring Disneyland to Phoenix. His idea was to make it a genuine theme park in order to resemble Disneyland but he wanted it to be an Arizona-themed theme park. And that is exactly what he created.”

Crandall tried to keep Legend City open year-round but hit a few hiccups during the cold and rainy months of January and February. The theme park eventually reduced its operating hours to weekend evenings and abandoned its one-price policy in favor of individual ride tickets, signaling that trouble was afoot.

That trouble manifested when Legend City closed in November 1964—less than 18 months after opening. Former investors took the theme park to bankruptcy court, where it was revealed that it was behind in salary, fire insurance and property tax payments.

In May 1965, Legend City reopened under a new business plan that made it much more of an amusement park—or permanent carnival—than a theme park. It changed hands four times, with each new owner driving it further away from Crandall’s original concept until its gates closed indefinitely Sept. 4, 1983.

Happy Trails

Bueker, who became a close friend of Crandall until his passing in 2016, says that Legend City never really drew the numbers of visitors that officials had hoped it would. Crandall had estimated one million annual attendees, but the theme park only saw about 500,000 visitors during its first year in operation.

“In my opinion, one of the problems was that the City of Phoenix was not really big enough yet in 1960 to host a world-class theme park—which is what Legend City aspired to be,” Bueker says. “We certainly did not have the tourism base either.”

Dr. VanderMeer agrees, noting that Legend City attempted to put Phoenix on the map as a tourist destination at a time at which the city was not yet ready for such a high-profile status.

“One of the tensions here is the extent at which you can make money off of tourists coming to your theme park and the extent at which you need to have locals coming and buying your tickets,” Dr. VanderMeer explains. “That balance never seemed to work out satisfactorily for Legend City.”

Dr. VanderMeer adds that there are a number of other explanations as to why Legend City was unable to hold its own alongside the likes of Disneyland, Six Flags and the country’s various other highly successful theme parks whose revenue this year is forecast to total more than $22 billion.

He explains that the value of the land in Phoenix is and always has been greater than the value of entertainment, and our high temperatures tend to be a deal-breaker.

“Disneyland and many of the other theme parks get summer vacationers,” Dr. VanderMeer says. “You have got kids who have the days free during the summer. Well, summer and outdoor activity in Phoenix just do not go together terribly well. It is far too hot. I think that is the fundamental problem for an outdoor entertainment center in Phoenix.”

However, the historian notes that Phoenix should not be frowned upon for its failure to keep Legend City around long enough for future generations to enjoy.

“How many places actually have a Six Flags or some other theme park?” Dr. VanderMeer asks. “Not all that many. In that sense, Phoenix is not unique. When you look at the longer history of amusement parks, Phoenix fits right into that pattern.”

Bueker agrees, adding that although people lament Legend City’s demise, it is actually quite surprising that the theme park lasted a full 20 years when the bigger picture is taken into account.

Of course, there have been plenty of projects that have been announced over the years—including Dreamport Villages in Casa Grande—but nothing has materialized yet. Castles and Coasters near Metrocenter is the Valley’s closest thing to an actual amusement park, and is nowhere near the Disneyland in the desert that Crandall envisioned almost 60 years ago.

“In a sense, the legacy of Legend City is that its perceived failure has discouraged anyone from investing in a theme park in Phoenix,” Bueker says.

“Now we have a huge population here that could easily support a park. But the shadow of Legend City seems to still be hanging over Phoenix and no one has come forward to replace it in all these years.”

Comments by Admin