Strength and Grace: The Inspired Work of Miguel Edwards

Writer Amanda Christmann

Photography by Miguel Edwards, Suzette Hibble and Lonnie McKenzie

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt was faced with some of the most difficult days in American history. The Great Depression, which began four years before his first term in office, had split the country at the seams. Families and communities were economically devastated in ways never seen before, and desperation and suffering wove dark threads into the fabric of American life.

Roosevelt knew that, to architect a solution for one of the worst crises in U.S. history, he would not only need to enlist help from the country’s leaders and intellectuals; he would need to empower writers, photographers and artists to bear witness to the stories.

These creatives set out to document the lives of their fellow Americans, and the work they did helped policymakers to understand the importance and urgency of the decisions they were making.

Today, we are facing different challenges as individuals, as communities and as a country, but art and ingenuity are no less crucial. Art, it can be argued, is the human thread in an increasingly impersonal world.

In fact, like Roosevelt, sculptor, world-renowned photographer and installation artist Miguel Edwards believes that art is far more than a side note. He believes that art is an incubator and an expression of the innovative thinking that has been integral to human expression, and even survival, throughout history.

“Inspiration and creativity are the antidote to the current trajectory of our society and environment,” he explains.

“There is so much darkness and distraction in our world. I love to create arresting beauty that causes a moment of pause or reflection—taking a moment when we’re not staring at a screen—and asking questions like, ‘What is that?’ or, ‘How does this make me feel?’

“An even loftier goal is that, if I can inspire people beyond asking questions and into being creative in their own lives, I would call that success.”

For his part, the New Mexico native has created strong roots among the Seattle arts community, encouraging other artists and creating opportunities for meaningful conversations. He served on the board for Center on Contemporary Art (CoCA) for just under a decade, and founded and ran an artists’ organization called Scartists.

Still, it is Edwards’ art that has given him a distinguished reputation among galleries, collectors and public art enthusiasts.

Edwards’ metal and glass sculptures are a study in movement and in transformation. From smaller private pieces to large public displays, he creates works that seem to defy gravity and create the illusion of motion.

His work is not only provocative for the viewer; it is also a source of challenge for the artist.

“I enjoy pushing my own personal and material boundaries,” he says. “It is the act of creation that defines my work, as much as it is the finished piece.”

From a workshop tucked in the ponderosa pines of Bend, Oregon, where he moved two years ago with his wife Corrina Jill, Edwards creates what he refers to as penumbra sculptures. He spends long hours cold rolling steel flat bars into graceful arcs and curves, then welding, grinding, sanding and filing them into often complex forms to be interpreted by the eye of the beholder.

“With steel, you can make shapes and forms that defy gravity,” Edwards explains. “You can create curving cantilever forms that look like they stand against our perception of gravity. There’s something conceptually neat about that.”

Energy of movement is an important element of Edwards’ work. His sculptures offer an unlikely balance between the unyielding properties of steel and the fluidity of graceful design.

“Some of my pieces are, in fact, kinetic, but even in those that are not, I like to convey motion,” he says. “Implied kinetics—that feeling of motion while things are actually standing still—is something I strive.”

Much of his most recent work integrates cast and blown glass, LED bulbs and sensors into his colorful steel designs, enhancing the dance between shadows and light. Each element creates a new layer of depth and leaves the indelible signature of an artist willing to push creative boundaries.

Ascent

One of Edwards’ pieces, Ascent, recently made its Arizona debut at Grace Renee Gallery. The brilliant red steel and cast glass sculpture rises nearly eight feet in height and stretches three feet wide, yet it exudes a nearly ethereal sense of grace. Separate elements intertwine symbolically as the entire sculpture seems to float weightlessly on a breeze.

Created for the Bellewether Exhibition in Bellevue, Washington where it was positioned in front of City Hall, Ascent has gained a following at exhibitions from Washington to CONTEXT Art Miami, including a two-year stint with the city of Palm Desert, California, and last summer in Sun Valley, Idaho.

It’s one of Edwards’ favorites, and it is also deeply personal.

“It’s a piece I love,” he says. “It’s an historical piece for me. It was inspired by a spiritual experience that my wife and I shared. It’s about transcendence, levity of spirit and rising up.”

Perseus I and II

In 2010, Edwards created Perseus I, a kinetic sculpture built for the CoCA’s “Heaven and Earth II” temporary sculpture exhibit at Carkeek Park. Soaring over 22 feet tall, Perseus I is wind-powered and kinetic. Solar-powered LEDs shine from red and blue crown-like expansions that top a moving pendulum balanced between a tripod of legs.

What makes Perseus I stand out—other than its original design and impressive size—is an unusual added element. Edwards collaborated with Tick Tock, a Pacific Northwest-based aerial troupe, to blur the lines between art and performance.

“People really loved Perseus I,” Edwards says. “Four or five years after the piece had been removed, there were still grooves in the lawn from people interacting with my piece of sculpture. It was a favorite for years.”

In 2016, Edwards topped that accomplishment with a second ideation of Perseus.

“Perseus II was my first big public art piece,” he says. “I started it the year my wife and I got married. It’s three-and-a-half stories tall and made from steel, cast glass, blown glass and LEDs. It’s kinetic and interactive, and we had to pass a city ordinance to place it there. Even the installers said it was one of their favorite pieces they’ve worked with.”

Perseus II was commissioned by Security Properties, a Seattle-based investment and development firm. It is featured outside of their trendy Janus Apartments building and has become a Seattle landmark.

The massive 35-foot-tall sculpture is integrated into the building itself, with one of its tripod legs passing through a metal awning. It is whimsical and memorable, eliciting the kind of curiosity that stokes Edwards’ creative fires.

After completing Perseus II, Edwards solidified his place among premier metal sculptors. He began to receive referrals for coveted commissions that challenged his artistic finesse and his problem-solving skills.

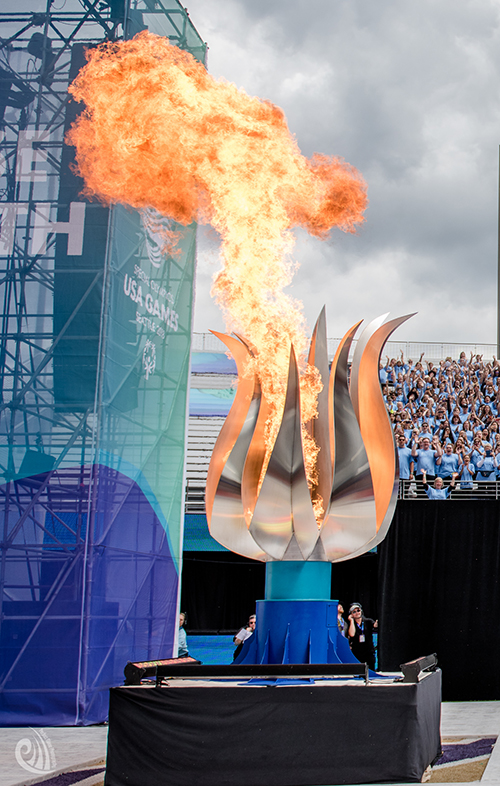

First, Microsoft came knocking. Then, the CFO of Chihuly Studios pointed to Edwards when Special Olympics needed an expert artist to create their epic cauldron—which he did with his characteristic panache.

Inspired Energy

As Edwards continues to create, he does so with a strong sense of purpose and a never-ending inquisitiveness that is evident in his work.

Defining that purpose can be a bit elusive for the artist.

“I feel like it’s changing all the time,” he explains. “It seems like the second I finish an artist’s statement, it’s obsolete.

“When you really get down to the meat and potatoes of it, I just love building beautiful things. It’s exciting to toil away, then take a step back and look at the finished piece and say, ‘Wow, that’s awesome!’ I’ve enjoyed that feeling as photographer and a sculptor my whole life.

“The other thing about making beautiful things is that inspiration and creativity are human traits that are more important every day.

“Energy cannot be created nor destroyed; it simply changes forms. These bold shapes and implied kinetics are about changing human energy and shifting it toward those places of creativity and inspiration.

“With the state of the environment and of humanity right now, I don’t think I will change the world, but if I can move the scale and get people to ask questions, I’ve accomplished something very good.”