Writer Amanda Christmann

Photography by Bryan Black

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he sands of time have a way of honing the past, shaping and polishing it so that generations to come can judge it more clearly. At times, the decades or centuries reveal horrors we hope to never repeat. But sometimes what is revealed is nothing less than greatness.

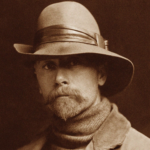

The life of Edward S. Curtis is one such epic. Curtis was a photographer who set out on perhaps the most incredible photographic odyssey in history, yet his genius was not recognized until long after he died.

Curtis’s legacy, 40,000 photographs, videos and audio recordings of long-gone indigenous languages, cultures and traditions, can only be found in private collections and a few select museums.

Cave Creek Museum has the distinguished honor of being among the few institutions where Curtis’s work can be seen. An exhibit titled “The Photography of Edward S. Curtis” will be on display through March 31.

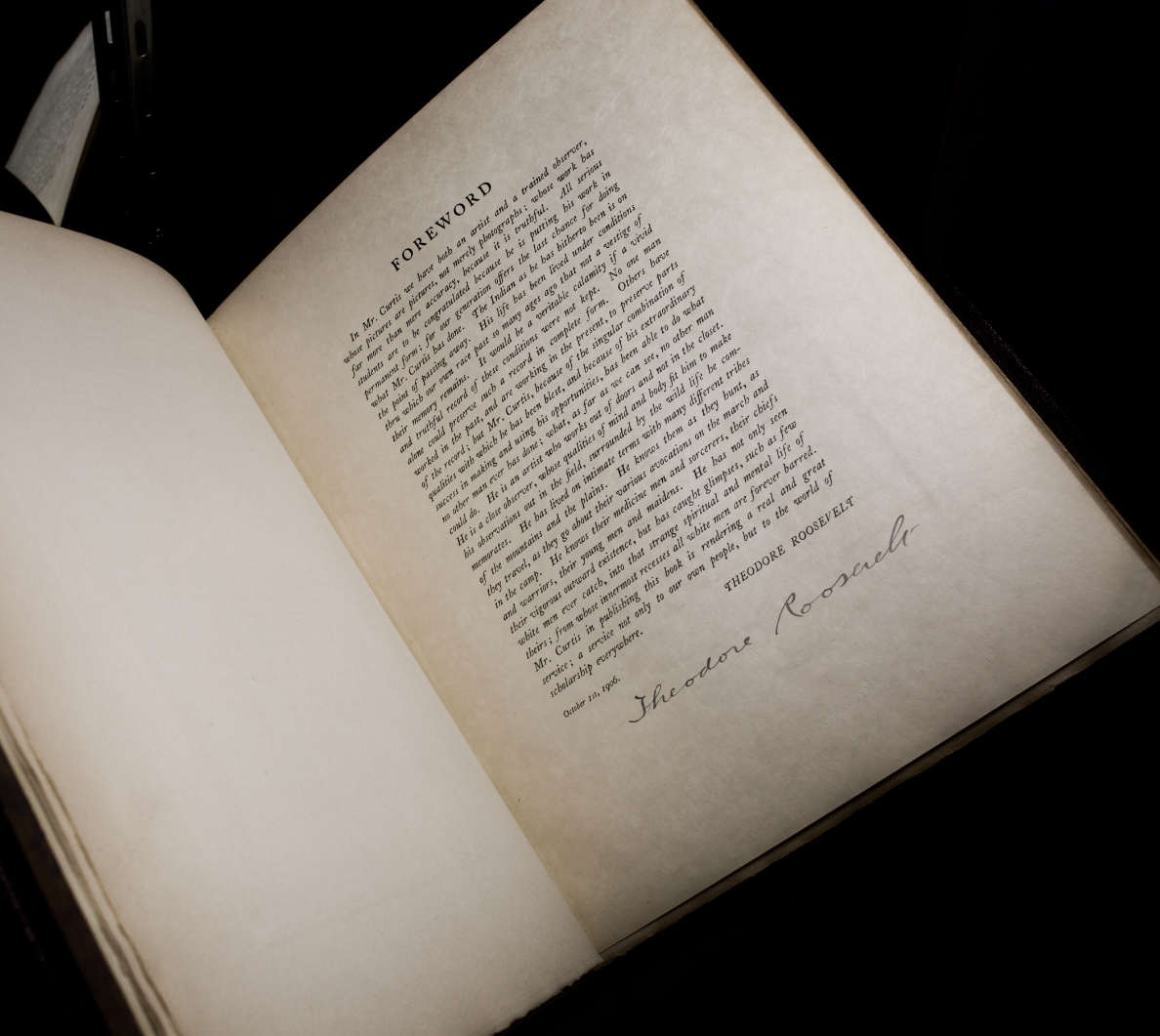

It took Curtis 30 years and cost him everything—his money, his reputation and his marriage—to complete. His opus magnum was a 20-volume set of 400 photographs called “The North American Indian,” now referred to by the US Library of Congress as “the most significant record of Native culture ever produced.”

Only 227 sets were printed, and it wasn’t until one was dusted off in the basement of a Boston bookseller in the 1970s that the world began to take notice.

Curtis’s work is nothing short of incredible, but his life-long quest to advocate for Native Americans, including his personal struggles, achievements and the criticism he received, is a story in itself.

Curtis was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin in 1868. His father had been a Union soldier and chaplain during the Civil War, and would later become a preacher, instilling his son with both a sense of ethical responsibility and love for the outdoors.

When Edward was born, the US was in the throes of an ugly period of history. More than 200 battles were fought between US troops and tribes from the Dakota Territory to Mexico from 1866 to 1875. The government had mandated that practicing Native religions and other traditions were felonies, although they often saw honoring treaties and social contracts as optional.

Though Curtis likely heard about what was happening to Native Americans in those dark times, he would later recall that it was an engraving that planted the seeds of his life purpose.

What was depicted in that picture was the largest single-day execution in American history. Thirty-eight Dakota Sioux Indians were hanged in Mankato, Minn. following the Sioux Uprising. It occurred 25 miles from the Minnesota town where the Curtis family would move in 1880.

Life through the Lens

Curtis’s father had brought back a lens from the Civil War, and at the age of 12, Edward used a photography manual to build his first camera. That moment would mark a crossroads in his life, as did the day he bought his first camera at the age of 18—a purchase his mother said was a waste of his money.

It turns out that it was not.

That camera was the gateway to Curtis’s journey. He moved to Seattle at 18, followed by his soon-to-be wife Clara, to form a partnership in a photography and engraving business. Local women found Curtis especially appealing. Through his lens, the handsome Curtis was able to portray their mundane lives as sophisticated and interesting.

By some accounts, Clara enjoyed the money Curtis brought in more than she enjoyed photography. Still, they had four children together and forged a life in the Pacific Northwest that would have likely remained comfortable had it not been for two chance encounters.

The first was with Princess Angeline, the daughter of the great Chief Sealth, for whom Seattle was named. It was illegal for Native Americans to live within city limits, but Angeline had been given an exemption. Well into her 90s when she met Curtis, she lived in poverty on the edge of town, digging clams for a living.

Curtis was enthralled. He offered to pay Angeline one dollar per portrait, a fee Angeline accepted enthusiastically. The details and expressions of her face that Curtis captured with his lens were unlike anything seen at the time. They earned him grand prize in an exhibition sponsored by the American Photographic Society. Princess Angeline died soon after in the city’s skid row.

That same year, he made a second life-changing chance encounter. While climbing Mt. Rainier, he stumbled upon a climbing party in distress. That party included George Bird Grinnell, editor of Forest and Stream magazine and founder of the Audubon Society; and Clinton Hart Merriam, had of the US Biological Survey and founder of the National Geographic Society.

Grateful for his assistance and impressed by his acumen, they invited Curtis along for the Harriman Expedition to Alaska as their official photographer. It was a wild card of fate that gave Curtis the opportunity to learn the basics of anthropological research—despite the fact that he hadn’t finished his sixth grade education.

Grinnell then invited Curtis to Montana to witness the last Sun Dance performed by the Plains Indians, and to Arizona to witness a Hopi Snake Dance. The seeds planted in Curtis’s mind began to germinate and bloom into an impassioned desire for activism and a pressing need to document the disappearing culture and faces of Native Americans while there was still time.

A Worthy Endeavor

The US Census indicated that there were only 235,000 Native Americans left in North America when Curtis began. Cultures were being forced into extinction by the US government and by Christian missionaries.

His only problem was funding. Curtis’s dreams were bigger than his pocketbook. He approached the Smithsonian Institution for funding only to be turned down, then made a fruitless trek through New York in search of a publisher.

Undaunted, Curtis bought a motion picture camera and used his own funds to set out for the Navajo Nation. He used his savvy to convince the tribe to allow him to photograph their sacred Yeibechei Dance. (They performed it backward, as they still do for secular audiences.)

The next years were a flurry of shows and opportunities. Curtis caught the eye of Theodore Roosevelt and added photographs of Geronimo and Chief Joseph to his portfolio.

Still, he was doing it on his own dime, and he was running out of money. Railroad magnate JP Morgan came to his aid. He agreed to plunk down a total of $75,000 to fund the project—a massive sum in 1906.

Curtis traveled by burro, boat and horseback from one remote tribe to the next, earning trust and gaining access to ceremonies and cultures never before opened to white people. He ennobled Native Americans with his work, portraying them as proud people—something that took white society at least another century to appreciate.

Half anthropologist, half activist, Curtis was driven by his desire to depict unadulterated Native cultures. It was his greatest achievement and his greatest downfall.

White laws and influences had infiltrated many tribes. He was known to bring along his own “Native” clothing and props, and even to use techniques akin to Photoshop to alter negatives so images would fit his version of “true” Native experiences.

His subjects didn’t seem to mind having things like clocks or umbrellas removed from photos, or wearing clothing that was not theirs; but today, critics take exception. By removing evidence of neocolonialism, they say, Curtis ignored the struggles and injustices Natives endured.

Curtis pushed on, but despite the generous backing from Morgan, he still couldn’t pay his mounting bills. His wife Clara was no longer interested in standing alone while Curtis traversed the country for months at a time. In a bitter divorce, she took him to court for all he was worth—and got it.

Curtis was broke and broken. He found himself completely defeated in California, where he shot film of fake Indians for Hollywood. His daughter Florence provided encouragement. Together, they filmed and photographed the last of his California Indian volume, then traveled to the arctic to complete the last series.

His was a feat that remains one of the greatest works of anthropological documentation.

Yet none of it belonged to Curtis.

A Worthy Ending

Curtis was so indebted to the estate of JP Morgan (the mogul had died years prior) that he was forced to sign away the project’s copyright. The Morgan estate sold his work in its entirety for $1,000 to a Boston publisher.

And there it sat.

When Curtis died in 1952, he received a meager 77-word obituary that spoke briefly of his authority on North American Indians. The last line simply read: “Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.”

Like many of the people, dances, languages, ceremonies and religions Curtis preserved in pictures, frames and audio, “The North American Indian” disappeared into obscurity—until a complete set of all 20 volumes was rediscovered in a bookseller’s basement.

That single set sold for $2.88 million at auction in 2013. Other few surviving sets have been equally coveted.

The Photography of Edward S. Curtis exhibit is a tremendous accomplishment for the Cave Creek Museum. It marks the first time it has been displayed in the Phoenix area.

“This is an exceptional collection with unique pieces that you won’t see anywhere else,” said museum executive director Karrie Porter Brace. “We are displaying ‘The North American Indian’ in its entirety, signed by Teddy Roosevelt and Edward Curtis.”

It’s a fitting acknowledgement for man whose extraordinary life was unrecognized for far too long.

The Photography of Edward S. Curtis

1–4:30 p.m. daily; Fridays 10 a.m.–4:30 p.m.

Closed Mondays and Tuesdays

Cave Creek Museum

6140 E. Skyline Dr., Cave Creek

$3–$5; children under 12 are free

480-488-2764

Comments by Admin