Into the Quiet

Writer Amanda Christmann

Photography by Bryan Black

[dropcap]E[/dropcap]nveloped by deep sofa cushions in his Scottsdale home, Max Hammond shifts nervously in his seat as he searches for words. I’ve asked him, in not so many words, to explain his art, and he’s struggling as he tries to articulate matters of the heart.

His chocolate lab, Luke, is excited to have a visitor, but from the moment I stepped into his comfortable, rambling ranch, it’s clear that, courteous though he is, this is Hammond’s personal sanctuary—a place where an easy silence settles into the corners, and where solitude is a comfortable friend.

The interior of the living space, once the home of notable Valley designer Lawrence Lake, is structured around a colonnade—a perfect gallery for Hammond’s work. Its studies in color and texture are a beautiful contrast to clean lines and turquoise pool standing in placid stillness just outside a large wall of glass.

On the coffee table is a photographic homage to mid-century abstract expressionist Franz Kline. Perhaps a little flustered, Hammond uses this tangent as a starting point. He lifts the book and flips through the pages to show some of Kline’s stark creations.

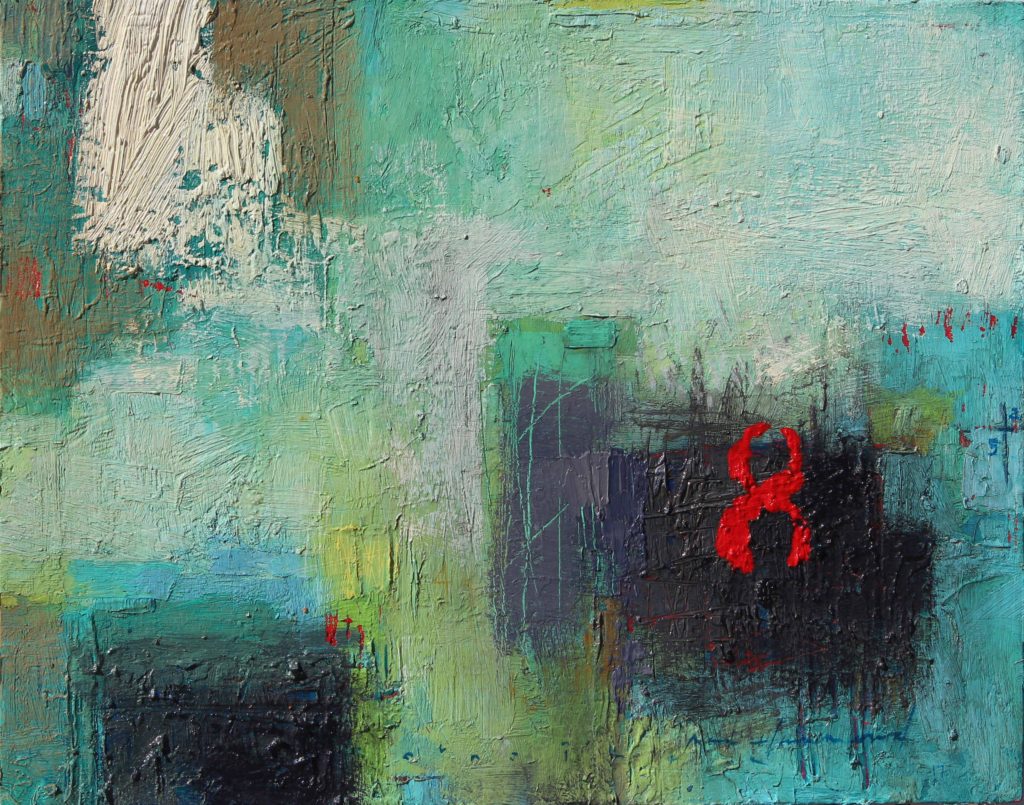

Like Kline, Hammond began as a figurative painter, focusing on figures and landscapes. Kline began his career in the 1940s by painting the colors and shapes of his coal mining childhood home; decades later, Hammond was influenced by the Great Salt Lake marshes near his rural Utah home. There was something about the abstract that called to each of them.

In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, Kline abandoned the form and structure of his paintings that he’d spent years perfecting, in large part because he’d become friends with other abstract pioneers, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Philip Guston.

Together, the four would wax eloquently about art, existence and the relationship between the two at New York’s Cedar Bar. They discarded traditional ideas about both, each instead embracing his own progressively avant-garde style of abstract expressionism.

For Kline’s part, he experimented with scale and eschewed color. Instead of fine art brushes, he began using house painting brushes to make broad black and white strokes resembling calligraphy on massive canvases. He developed an oeuvre that bore little resemblance to the physical world, but that broke through artistic barriers in bold, new ways.

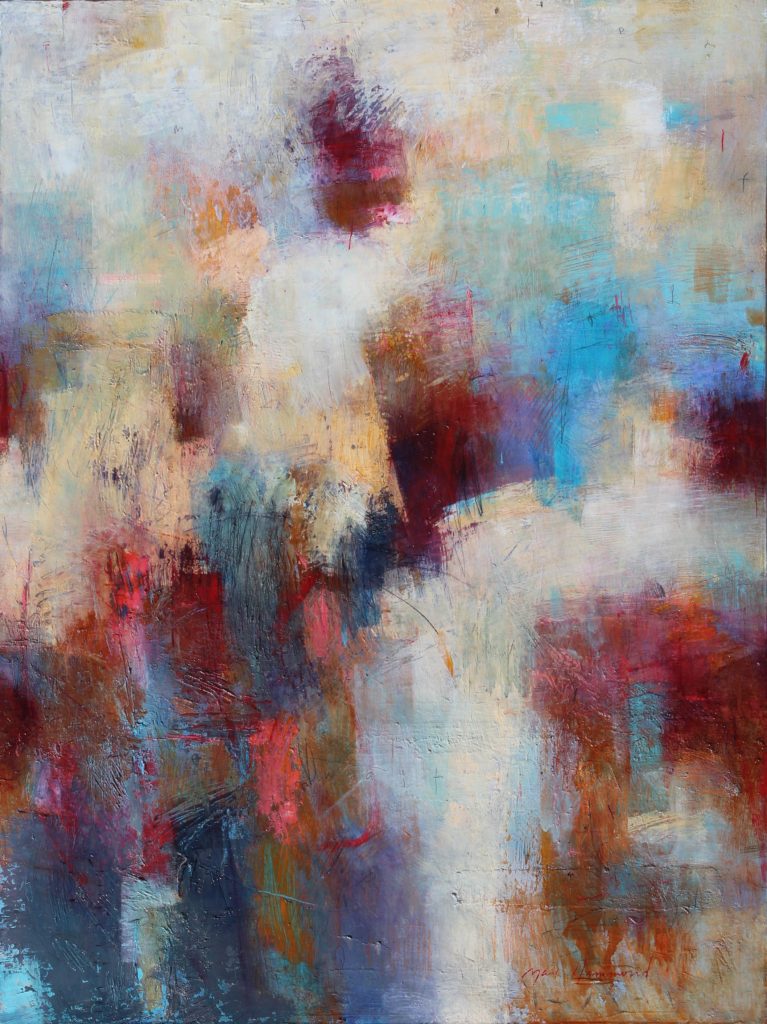

As much as Hammond admired Kline, and despite their similar artistic beginnings, his work took on a very different personality. While Kline’s stark black and white brush strokes reflect and elicit the angst and anger that under lied—and perhaps even undermined his life, Hammond’s work is far more complex. In fact, it could be argued that Hammond’s thick layers of color, thoughtful transitions and unexpected details, some even whimsical, are more emotionally evolved than Kline’s work. “They seem to end up rather quiet,” Hammond says of his art, glancing toward the floor through black brow line rimmed glasses. “I don’t know that I’ve ever set out to make them that way, but they seem to end up that way.” Sharing time with Hammond in his home, the difference appears obvious; it’s not so much a difference in technique or perception of art so much as it’s a reflection of the very soul of each artist.

Wearing a blue camp shirt and practical jeans, he measures his words before he speaks. His voice is gentle and his thoughts are deep. It is nearly impossible to imagine him in the throes of the boozing and brawling that Kline became known for. That simply would not be Hammond, or his work.

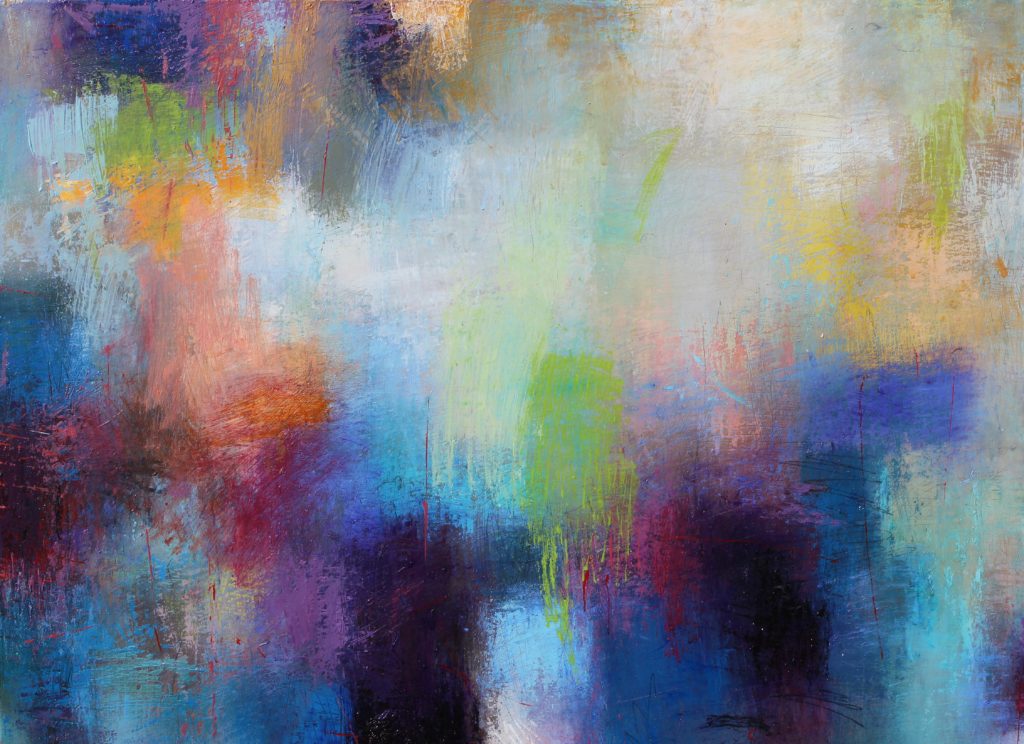

Following his early Utah childhood, Hammond attended University of Utah to learn classical figure drawing. After earning his bachelor’s of fine arts, his eyes were opened widely during a trip to Mexico. He was struck by the vivid colors there—primary hues that seemed to form the very foundation of Mexican culture.

When Hammond entered Arizona State University to study for his master’s degree, one of his professors noticed disconnect between his student and the art he was creating.

“He said, ‘You like the color, line, texture and pattern of paint, but try dropping the figure,’” Hammond says. “So I dropped the figure.”

He’d also held on to the memory of a photograph he’d seen years before of one of Kline’s pieces—a rare one that featured a splash of color—in a Time magazine he’d found in the library.

“I was a young teen at the time, and it got me fired up for some reason,” Hammond says. “It made me feel something. I don’t really know how to describe it.”

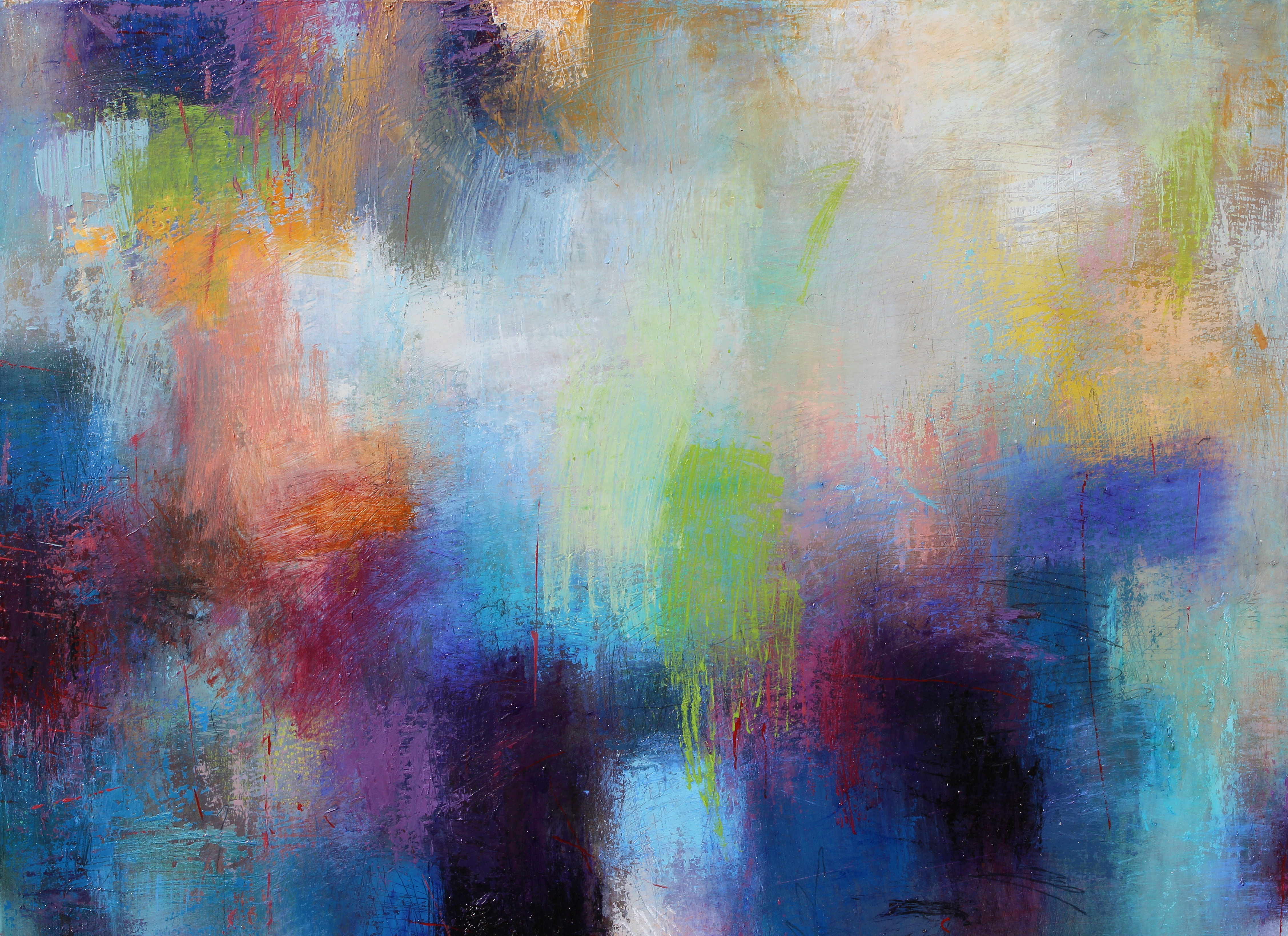

Those two impressionable moments became a fortuitous combination. They launched Hammond’s foray into abstract expressionism—one that would lead him to become a widely collected artist with work in the permanent collections of the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Neiman Marcus, Nordstrom, Finova Corp., the City of Scottsdale, and the City of Mesa, among others.

Today, married to wife Michele, a city planner, and a father of three, Hammond leads a much more balanced life than Kline, and the “quiet” of his work reflects that.

In fact, he often equates his process to the hikes he loves to take near his Scottsdale home and in southern Utah, where he owns 11 isolated acres of land.

“Hiking is a great metaphor for painting,” he explains. By now, he is visibly more relaxed. “You wander around on a trail, and maybe you end up somewhere and maybe you don’t.

“With painting, I get a little lost in my head, mixing colors and trying to make it feel right. The composition gets worked out along the way. One area might begin dark, but it becomes light … I scratch it off and put it back on. I just keep going until it feels right.”

Based on his reception for the last three decades, he’s accomplishing that goal and developed a following doing so. He has dozens of solo shows, public art projects and exhibitions under his proverbial belt.

For the last 16 years, in addition to galleries around the country, Hammond’s work has been featured at Scottsdale’s Bonner David Galleries. This month, he will hold a special show: an homage to Franz Kline.

Kline is quoted as saying, “I paint not the things I see, but the feelings they arouse in me.”

In this way, Kline’s and Hammond’s thoughts and purpose are parallel.

“I want an emotional reaction instead of a thinking reaction,” Hammond explains with his dog now fast asleep on the cushion beside him.

“I just want to make a little spot of quiet in people’s lives.”

bonnerdavid.com