Instinct & Ingenuity: The Art of Jason Adkins

Writer Shannon Severson

Photography by Bryan Black

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he greatest piece of advice that artist and set designer Jason Adkins ever received was from his high school art teacher back in his native Tennessee: “Don’t overthink it.”

Frustrated with her 17 year-old student’s consistently slow work pace, she tasked him with completing paintings in 20 minutes, something he first considered impossible. Nevertheless, with practice, it became a freeing mantra.

“That advice was the start of my style and my career,” says Adkins, sitting in the light-filled front room of his North Mountain home. He’s surrounded by large canvases and a few stray boxes that remain after his recent move from San Diego. “It helped me earn a college scholarship to Eckerd College in Florida and cemented my desire to make art my primary pursuit, no matter what it took. I like to work quickly now and I like to paint as often as I can.”

Adkins’ mother often reminds him of what he told her about his dedication to painting as he was finishing graduate school at Claremont Graduate University.

“I told her that if I live in a cardboard box, painting on cardboard with a stick, using wet cat food, it is by choice,” says Adkins. “I don’t remember saying it, but it speaks to what I will do in order to keep painting.”

Adkins has definitely lived the starving artist life at times, but when Los Angeles Times art critic David Pagel took note of his talent, he gained his first big break with a solo show at LA’s Western Project Gallery in 2008. It opened the day after President George W. Bush publicly announced that the United States was officially experiencing a recession.

“It was a great experience, but the worst possible time,” says Adkins. “Everything crashed in 2008. Galleries were closing everywhere and Los Angeles was an expensive town to rent—even my cheap studio in a rough area of town. I worked in a friend’s studio for awhile, did odd jobs to pay the rent, and even switched to making charcoal drawings on paper for awhile when I couldn’t afford paint.”

His tenacity for finding work also led to a very Hollywood moment when one of his sculptures was used in director David Finch’s 2010 movie, “The Social Network.” Ultimately, Adkins made the decision to leave Los Angeles for Las Vegas that year, where he had several gallery shows and an unusual residency at P3 Studio in the Cosmopolitan Hotel. “Rapture,” a behemoth 96-inch by 72-inch oil and spray paint on canvas teems with color. He continually rotated the canvas throughout the process to avoid repeating patterns.

“It felt odd at first to paint large canvases while drunk people dressed in flashy outfits wandered through and filmed me on their phones,” says Adkins. “But, after awhile, you forget and just go with it.”

He and his wife, Dhyana, a high school theatre teacher, moved to San Diego in 2013 where he was a professor at Mira Costa Community College and ran an art events business on the side. Here in Phoenix, a similar concept, called Paint-A-Holics, will bring wine and paint nights to individual homes, as well as to bars and restaurants around the city.

The family’s departure from California this year brings them closer to Dhyana’s family, and Arizona’s lower cost of living gives Adkins more freedom to create on his own terms, without the requirements that being with a gallery might entail.

“I don’t want to be told to paint only what will sell,” says Adkins. “When we had our son, Xander, in 2014 and I thought I might not have time to paint as much, but that hasn’t been the case. I spent four months creating my mandala-inspired Element series representing water and earth while he was napping. It motivated me to get back to painting more often. Not being with a gallery, I’m able to experiment and paint in the way I want to.”

That independent streak is also apparent in the tools and methods Adkins uses to create primarily large-scale pieces with unusual methods and materials. His preferred tools lean more hardware store than art supply emporium. Inexpensive, multi-pack paintbrushes and foam paint rollers accompany palate knives to create the broad, bold brush-like strokes on pieces such as “Mint Split” and “Stickle.”

“Over decades spent painting, I’ve found that you need to look around at everything in your studio and see what can be used as a tool,” says Adkins. “You get wide strokes with a palate knife, but you can’t get it to look like a brush. Using a glove to hold the foam roller steady creates the look of a brush. I’d rather spend on paint and canvases than on expensive brushes.”

He creates thick layers in oil paint, and spray paint, which he terms “the poor man’s paintbrush,” to create abstract landscapes like “Beast” and “Sloop Loop” that are full of movement and mystery.

The aerosol cans that most associate with graffiti or backyard projects become something different in Adkin’s hands. He uses different quality levels, spray distances, direct application onto palate knives and even varying studio temperatures to create a range of effects. The feel of these pieces is often dystopian, like something nefarious teems just below the surface.

The Morphing series, exemplified in “Goldfinger,” is inspired by the sculptures of John Chamberlain, and includes more structured abstracts composed of oil paint, applied with palate knives, and spray paint, layered at different angles and distances.

“I want to depict something that is living in the landscape, but isn’t necessarily comfortable in the landscape,” says Adkins.

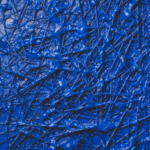

His heavily textural series, including “Alien” and “Gold,” is created with Bondo, an automotive repair resin that, at high temperatures can be drizzled a la Jackson Pollack. After curing time, he utilizes spray paint layers from different angles to layer color over pieces that evoke the unusual topography of a strange landscape. “Blue Pendant” is made with a random, pick-up sticks pattern of cheap paintbrushes, rocks, plastic lids, and layers of Bondo and glitter.

The recent move meant a break from painting, but he’s ready to get back to it and will continue to explore themes of rebellion and identity with the development of an alter-ego that will allow for him to experiment with total departure from his past work.

“I’ve never felt more inspired by what I need to do artistically,” says Adkins. “This is the longest I’ve gone without painting in the past 24 years, and my head is full of fresh and vibrant ideas.”