Imprints of Life

How Sharing His Story Became Veteran Joe Brett’s North Star

Writer Joe Brett // Photography Courtesy of Imprints of Honor

“War is the place where life and death meet,” wrote Sun Tzu over 2,600 years ago in the now-famous “The Art of War.”

Tzu tells us that a sound moral compass is the No. 1 necessity for sending troops off to win wars. Is the greater good worthy of sacrificing the deaths of young men in pursuit or defense of such goodness? The people and the military must all agree with this moral compass if the war is to be won.

History also tells us that the DNA of young men and teenage boys makes them the best ages for fighting wars. They have young bodies filled with testosterone and young minds eager for manhood and conditioned to kill or be killed for a cause greater than self. We veterans remember a phrase from our training: “What is the spirit of the bayonet? To kill!” was our joint, enthusiastic response during bayonet drills.

It seems the entire nation is with us young men and women as we enlist in the military to be reborn again as soldiers, sailors, Marines, airmen, guardians and Coast Guardsmen.

Professor Joseph Campbell in his “The Power of Myth,” “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” and characters in the Star Wars movies speaks to this universal truth: “Young men and women leave the comfort of their homes and are sent off to undertake the ordeals of vigorous training in which their heads are shaved, they are given new uniforms and new identities and are born again as warriors.” Their old lives are left behind as their new adventures unfold.

In Vietnam as a young aerial artillery observer flying the DMZ, my orders were to “get the body count.” Search and find enemy soldiers and kill them by directing artillery, bombs and napalm on them. The body count was data used to calculate the cost per kill measured against the political leverage for peace talks in Paris. It turned out that the North Vietnamese had the better moral compass as they defeated the most powerful country on earth, the United States.

A week before the end of my tour, and sipping beers with two friends, I was on top of our unit scoreboard for kills. And my dreams were of those who got away, and the nightmare of guilt feelings over the death of a mate with whom I had switched flights. War! Where life and death meet so randomly. I was asked, “Joe, are you going hunting with friends when you get home?” Hunting? Are you kidding me? I couldn’t kill anything!

What then of the moral compass of all U.S. veterans who were born again to fight in Vietnam but returned home as unpopular reminders of a lost cause and war? How do we become empowered to take on the tasks of becoming reborn as civilians, knowing what we now know from our wartime experiences?

My search for the meaning of being alive put me through the crude adventures of drinking and spiritual awakening of getting sober, going off to Harvard Kennedy School in hopes of meeting people of the world, then working in Indonesia and the former Soviet Union and somehow winding up in Arizona where I became involved with Sister City Programs and the Veterans Heritage Project, now Imprints of Honor.

It was in telling my story to [Imprints of Honor founder] Barbara Hatch and her students that I finally was able to put all my adventures, failures and victories into a storyline that gave meaning to my being alive. And I realized my story was not very different from all veterans from all human history.

The biggest lesson I learned was that I am not alone. Joseph Campbell and his “The Power of Myth” became my guru since my spiritual awakening of becoming sober in 1987.

It was in telling my story that led to listening to other veterans like Rick Romeley and Tom Kirk tell their stories that I was able to finally put myself into harmony with all veterans from all wars from all times. These heroes told of how they overcame thoughts of suicide when they began to think of how their experiences could be of help to other veterans — like me!

It is in helping others that we help ourselves the most. Telling our stories to students is the North Star on our new moral compass. Imprints of Honor, in words and deeds.

My survivor’s guilt over the deaths of battle mates is a common experience among veterans of the world. Jonathan Shay, M.D., wrote a book, “Achilles in Vietnam,” in which he wrote of the moral wounds of war suffered by Achilles and Vietnam veterans.

Moral wounds of war and PTSD are now well-known diagnosed traumas of war that were introduced into our vernacular by the return of Vietnam veterans, their moral compasses damaged and needing to be fixed.

As I lectured on the topic of moral wounds, I found this ancient quote from Alexandre Dumas and his 19th-century classic “The Count of Monte Cristo”:

“Moral wounds have this peculiarity — they may be hidden but never close; always painful, always ready to bleed when touched, they remain fresh and open in the heart.”

In telling stories we get the pain out of our minds and into the light of healing. It is in helping others that we heal ourselves. Veterans take on a new duty of using their survival of physical, mental and moral wounds to help others.

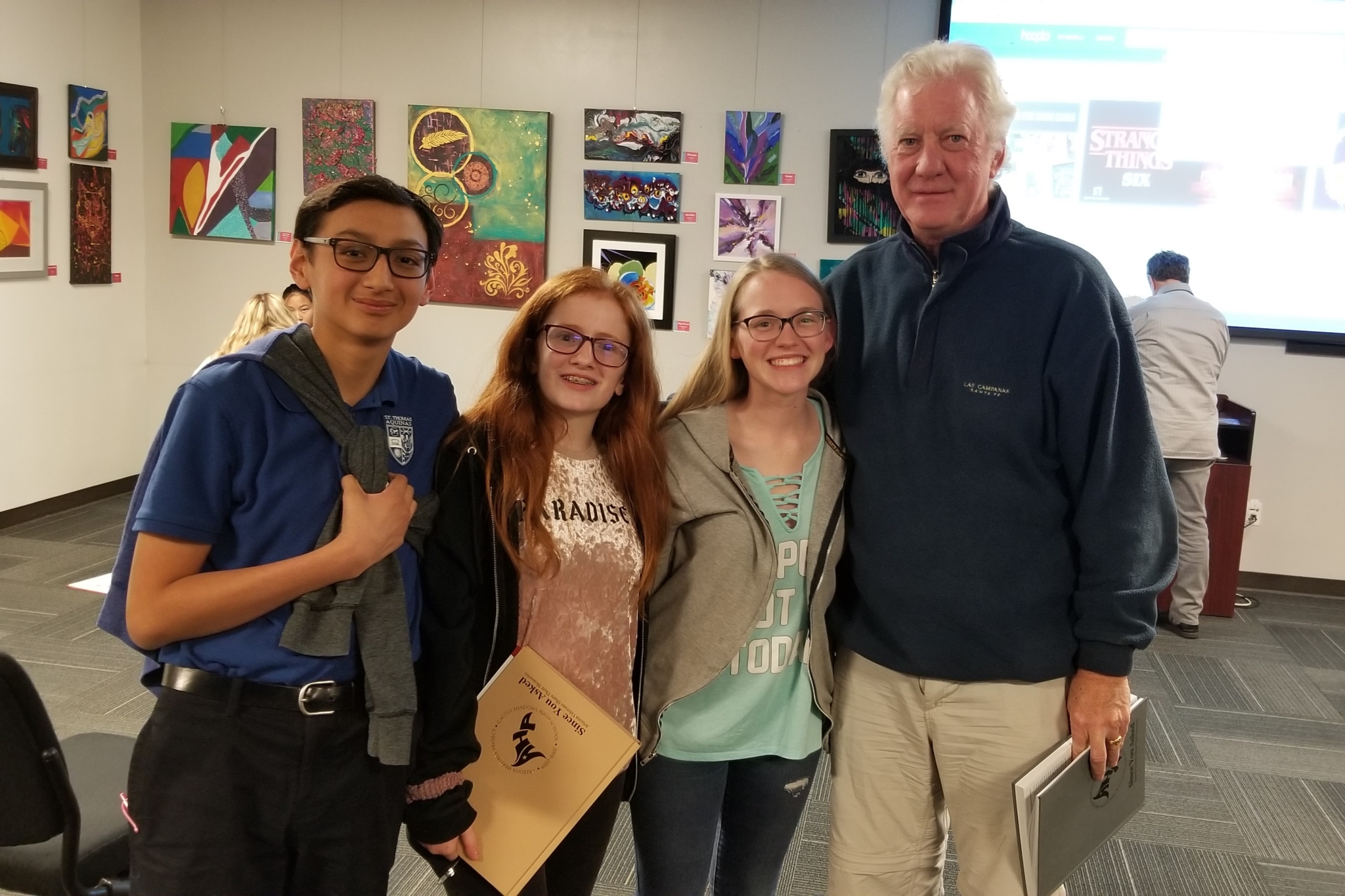

Sharing our stories with our precious students is a gift that keeps on giving. I am never more blessed than when a former student sees me and lights up with a smile and reaches out for a hug. Students are healing veterans. Many thanks to Imprints of Honor for helping me get to this point!

About the Writer

Joseph Brett served as a U.S. Army first lieutenant, aerial artillery observer and forward air controller with the 108th Artillery Group in Dong Ha, Vietnam, from 1969 to 1970. Flying the DMZ from the South China Sea to Laos, his mission was to hunt for North Vietnamese Army soldiers and direct artillery, bombs and napalm strikes — an experience that resulted in moral injuries that would shape the rest of his life.

In retirement, Brett has devoted himself to understanding and healing from the moral wounds of war. His veteran advocacy began in 1980 as founding member and first president of the Capital District Vietnam Veterans Association in Albany, New York. He later served as executive director of the New York State Temporary Commission on Dioxin Exposure (Agent Orange), appointed by the governor.

Brett’s ongoing work includes serving as a volunteer guide at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. (1994), board director for the Veterans Heritage Project (2014-2017), and co-facilitator for the Institute for Healing of Memories retreats for veterans with PTSD. He produced, created and co-hosted 40 episodes of the podcast “Front and Center USA,” featuring speakers from Arizona State University’s Center on the Future of War, and contributed to “Moral Injury: Towards an International Perspective” (2017). He has co-facilitated lectures on moral injuries with Pulitzer Prize-winning author David Wood at the University of Connecticut.

Brett holds an MPA in international development from Harvard Kennedy School, an M.S. in secondary education administration from State University of Minnesota, and a B.S. in economics from St. Bonaventure University. His international work has taken him to the former Soviet Union and Indonesia as a project manager and assistant for public administration programs.

His writing has appeared in Harvard Magazine and Wake Forest Magazine.