Writer Joseph J. Airdo

Photography Courtesy of USC Digital Library and U.S. Library of Congress

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Dorris Opera House may sound like a mere myth to some thanks to the limited remaining evidence of its existence and the tall tales of its heyday that involve a “massacre.” However, it is in fact one of Phoenix’s most significant pieces of history, contributing culture to the city thereby putting it on the map and stimulating its growth.

“Opera houses were very important for virtually any community,” said Dr. Philip VanderMeer, Ph.D., an emeritus history professor at Arizona State University. “They were a way for a small city or town like Phoenix to say, ‘Look! We’re cultured! We’ve got opportunities here!’”

Dr. VanderMeer specializes in American history and has a particular interest in the history of Phoenix. In 2002, he wrote “Phoenix Rising,” a book about the history of postwar Phoenix. In 2011, he published a follow-up book titled “Desert Visions and the Making of Phoenix, 1860-2009,” in which his research on the Dorris Opera House appeared.

Contrary to popular belief, Phoenix was not a Western town in the traditional sense of the term. Rather than being known for cattle ranching and mining, the city was primarily a hub for agriculture. Its access to water and the fertility of its soil made it appealing to early settlers. But its growth depended on attracting travelers and new residents.

“Phoenix is really trend-setting in history,” Dr. VanderMeer said. “It’s a great model for the shape that cities have taken. Looking at how Phoenix grew and why it grew is important. What made Phoenix most successful was its leadership, which combined interest in high-tech, quality education, military contracts and bases and providing a full range of cultural amenities.”

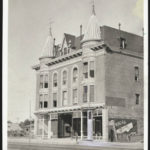

The Dorris Opera House is an example of one of those cultural amenities. It was particularly notable because it was a large, three-story, brick building as opposed to a wood building that could have easily burned down—as they often did in those days.

Architect S. E. Patton began construction on the Queen Anne-style theater in 1896. Boasting a pair of gorgeous conical towers, 20 bay windows and a 1,200-person capacity, the project cost $35,000—which, adjusted for inflation, would translate to about $1 million today.

Retail stores sat on each side at ground level while a simple marquee and vertical sign marked its entrance, which led down a long corridor to the theater. The theater’s ceiling featured a breathtaking mural of three North American Indian maidens.

“Phoenicians were looking to adopt styles that were popular elsewhere,” Dr. VanderMeer said. “They imitated architecture from the East because those were the people they were trying to impress. It was not until further into the 20th century that architecture in Phoenix really began to shift away from that.”

Patton’s Grand Theater, as it was originally called, opened its doors Nov. 2, 1898 with a presentation of the play “At Gay Coney Island,” which played to a sold-out audience. Similar to other theaters at the time, the venue played host to a wide range of entertainment over the years—from plays and musical events to book readings and movies.

The theater made national headlines on Dec. 16, 1899, when actors Paul Gilmore and Lewis Monroe were shot on stage during what came to be called the Great Gilmore Massacre. A chorus fired muskets that were supposed to be filled with blank cartridges during a battle scene in a touring production of “Don Caesar” at Patton’s Grand Theater. However, the muskets were mistakenly filled with small missiles intended for target practice.

The accident eventually cost Monroe his life as a result of lockjaw associated with a bullet wound to his hand. The production’s star Gilmore received six bullet wounds, with the worst being to his legs. He was initially not expected to survive, much less ever appear on stage again, but doctors were able to remove a bullet from his knee in March 1900. He returned to work in October 1900 for a production of “Under the Red Robe.”

Despite Gilmore’s recovery, the incident sparked rumors that his acting troupe was jinxed—especially when, just a few days later, actress Kathrine Kidder fainted on stage due to extreme exhaustion during one of the troupe’s productions. She hit her head so hard on the floor that even audience members in the back row of Patton’s Grand Theater could hear the thud.

Patton sold the theater to E. M. Dorris on Dec. 29, 1899, just two weeks after the Great Gilmore Massacre. Dorris renamed the theater the Dorris Opera House, the name to which it is most commonly referred today. It was then that the theater played host to not only performances but also Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association meetings. Behind the opera house doors was formed what is now known as the Salt River Project.

“[The Dorris Opera House] was a multi-purpose facility,” Dr. VanderMeer noted. “Theaters were among the very first air-conditioned buildings in Phoenix so that made them especially attractive. When Phoenix was starting out in the 1870s, there were essentially no public buildings, so meetings were held in places that were large enough, like saloons. Opera houses then became available as a place in which groups could meet.”

The theater continued to change names over the years as it changed hands. In the early 1910s, it was renamed the Elks Theatre and was the official home of Elks Club meetings. Notable performances during this time included the play “Pirates of Penzance,” the film “Birth of a Nation” and a concert featuring John Philip Sousa—the conductor who composed U.S.’s National March “The Stars and Stripes Forever.”

The theater was renamed again to the Apache during the Great Depression. In 1957, it changed names one final time to the Phoenix Theater when it was purchased by John Diamos and his brothers, who also owned theaters in Tucson, Nogales, Douglas, Bisbee and Tombstone. During this time, it served primarily as a movie theater.

But by 1965, the theater’s heyday had long passed. Whereas Phoenix once featured a pedestrian business environment in which retail stores, restaurants and entertainment venues were situated within walking distance of one another, traffic and shopping malls threatened and eventually caused the collapse of the traditional downtown area.

“Starting in 1968, movie theaters were being built in malls,” Dr. VanderMeer explained. “Malls were designed to be suburban downtowns. That was a major shift. There were no people going downtown to see movies so these places kind of dwindled. [The Dorris Opera House] was one of a number of buildings that were really not being used, as there was no particular use for them anymore.”

The building that once played host to spectacular performances for sold-out audiences eventually served as nothing more than a municipal annex for city clerk election materials. Over the years, its conical towers disappeared, its bay windows were bricked in and its interior art was hidden behind political posters.

Phoenix Mayor Terry Goddard and others attempted to spearhead plans to preserve the historic building but the Orpheum Theatre—located just about one block to the east—eventually earned more support. The cost to restore two similar theaters to their former glory would have proven to be too high, so the Dorris Opera House was destroyed in 1985 to make room for the Phoenix Municipal Court.

Interestingly, shopping malls—the very thing that killed the Dorris Opera House and other downtown Phoenix attractions—have recently seen a decline in foot traffic as people head online for their retail needs. As a result, outdoor shopping concepts that resemble downtown Phoenix’s pedestrian business environment complete with restaurants and entertainment venues are striving once again.

“You have a change in the last 15 years, as people don’t want that internal experience,” Dr. VanderMeer said. “It’s very clear across the country and Phoenix is part of that national trend. It is a pedestrian-oriented [trend] with people wanting to go outside.”

Just as they did when the Dorris Opera House was the prime example of Phoenix’s cultural prowess.

Comments by Admin