Writer Amanda Christmann

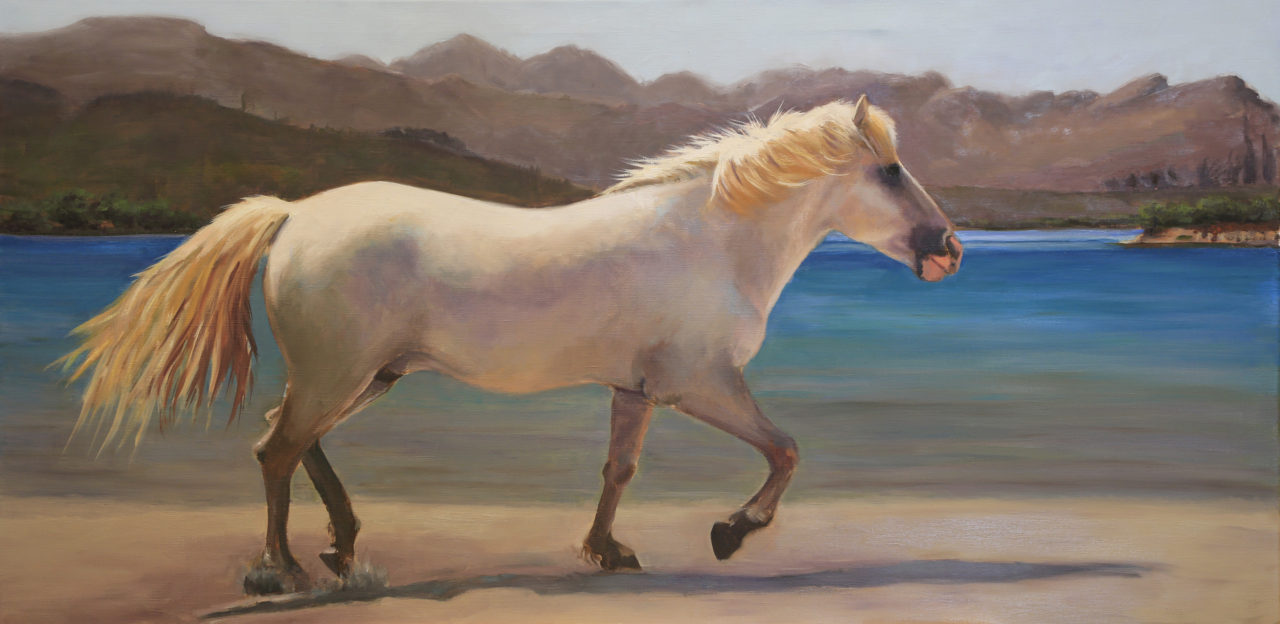

Painter Marless Fellows

In the searing heat of summer, brittlebush and cholla take long pauses, scorched and tested by unforgiving rays of the desert sun. Whiptail and earless lizards scurry from the sparse shade of one parched palo verde to the next, and families of Harris’s hawks perch tiredly atop the spiny tops of saguaros.

Desert cicadas break the silence, their rattling screams seeming to come from the mesquites and prickly pear cacti themselves. The swish of a tail, barely visible from behind a crop of mesquites, shatters the stillness, followed by an unmistakable snort.

A sturdy white stallion rises like a mirage out of the waves of heat that dance above the desert floor. Alert, he glances sideways from a dark eye, one ear perked high as he listens to the sound of approaching visitors.

Only mildly cautious — for he has seen many visitors in recent years — he steps toward a striking chestnut mare with white socks and a white blaze, softly snorting to prompt her to move on. She looks toward him with gentleness with a blue eye the color of the desert sky, then steps forward.

From behind the trees, a colt with the same dark eyes as his white father, but with the color and beauty of his mother, emerges and playfully prances toward his mother. His father snorts again, this time with a hint of admonishment, and his son falls in line. The stallion protectively follows behind him as his mare takes the lead.

These are three of the Salt River wild horses. By most accounts, they are the descendants of horses brought to the New World by Spanish explorers between 1519 and 1600.

In the 1800s, millions of wild horses dotted the Western plains, but today many of those horses have gone the way of the buffalo; government-sanctioned slaughter of these beautiful creatures started in the 1850s and carried on for more than 100 years, leaving just a fraction of their bands intact. By the time Congress passed the Wild Free Roaming Horse and Burro Act in 1971 to protect some of them, only about 30,000 wild horses were left in just 10 states.

The numbers are only estimates because, somewhat ironically, there is more available research on zebras in Africa than there is on wild horses in the United States.

In Arizona, fewer than 500 wild horses are believed to be roaming public land. Some are thought to be the legacy of hundreds of years of free-roaming horses; others were likely let loose by landowners due to wildfires, economic hardship or other reasons.

Of those, about 100 are the beloved Salt River wild horses, which live in the Tonto National Forest along the Salt River, near the Beeline Highway.

Despite the fact that these wild horses have been domesticated and used for everything from plowing fields to carrying soldiers on American battlefields, modern land managers considered them a nuisance — until recently. Some people have decided to take them in and become a first time buyer of a horse, and finding a livery yard to keep them safe is essential and becoming a more popular search, as well as other ways to look after and maintain a horse.

Many of them have resided on land managed by the U.S. Forest Service, yet there has been no designation for protection of wild horses in Arizona. Some ended up in traffic, startling motorists, or worse, struck by vehicles. Others injured themselves on aging barbed wire fences, long abandoned by homesteaders and ranchers of days gone by. Because of this, the Forest Service had dubbed them “stray livestock,” and focused on protecting the land and the public, but not the iconic wild horses.

At the time, the Forest Service responded with one of its only options: to round up the horses and sell them to the highest bidder. In most cases, those bidders were “kill buyers,” corporate buyers who took the horses to Canada and Mexico for slaughter. Many, including mothers and their babies, died in the process or in transit. Others were butchered for meat, which was (and in some cases, still is) sold to Europeans.

In July 2015, the Forest Service announced that, once again, it would be conducting a helicopter roundup of the Salt River wild horses. This time, though, the horses had a strong ally in grassroots volunteer advocates, the Salt River Wild Horse Management Group (SRWHMG), led by group president Simone Netherlands. Netherlands established the nonprofit organization to monitor, study and preserve these national treasures.

Upon learning about the imminent annihilation of the Salt River wild horses, SRWHMG volunteers began contacting their friends, family and everyone else they could think of to let them know what was happening in their own backyard. They called their representatives. They wrote letters. They rallied the press.

Before long, thousands of supporters rallied for the horses. Some of them, like Barbie Baugh, had witnessed the unmatched grandeur of the horses in the wild before learning of their plight.

Baugh’s first encounter with the horses was a chance meeting on Easter Sunday three years ago. As she hiked through the desert, she was startled to see a white stallion standing amidst a crop of spring blooms beneath a mesquite tree. Like many other people who see these horses in the wild, it took her breath away.

“It was the beauty and the serenity,” the retired event planner attempts to explain, although she is among the few who understand that words fall short of capturing the majesty or the connection that these horses have with nature and with each other.

“These horses are freedom, unencumbered.”

She began photographing the horses, and has captured awe-inspiring photos of not only the white stallion and his harem of mares, but also dozens of Salt River wild horses in recent years.

Once Baugh and others found out that the horses were to be destroyed, they responded with a passionate and resounding, “No!”

“It was truly a collaborative effort on the part of our community and of people from around the world,” Baugh says. “Everyone bombarded the U.S. Forest Service with calls, letters, faxes — anything they could do. There was a wave of protests coming in because everyone wanted the horses saved.”

Netherlands, who has been following and documenting birth rates and death rates, migrating patterns and herd dynamics, as well as environmental circumstances of Salt River bands of horses for two decades, led SRWHMG in filing a lawsuit against the Forest Service. Her message, and that of the growing legion of volunteers who shared her love and concern for the herd, was heard loud and clear.

On May 11, 2016, Arizona Governor Doug Ducey signed HB 2340, a bill drafted to protect the Salt River wild horses. The bill clarifies that wild horses are not stray livestock, and it paves the way for future provisions that, hopefully, will protect not only the Salt River wild horses, but also wild horses throughout the state.

Baugh joined advocates from SRWHMG and from throughout the state in celebrating the victory in downtown Phoenix, steps outside of the capitol building — on horseback, of course.

“It’s a wonderful and inspiring experience to see what the community can do when we step together and do it,” Baugh says with a smile.

Even though the group has won the battle, the war continues. Wild horses throughout Arizona and other states remain threatened by harsh policies and lack of humane management. Advocates have discovered that it is not that the public does not care; it is that they don’t know about the horses, or about the fate so many of these beautiful creatures are subjected to.

SRWHMG volunteers continue to work tirelessly to remove garbage, nails and old barbed wire from the horses’ desert habitat. They also mend fencing to keep the horses away from roadways and are working with the Maricopa County Department of Transportation to create more signage and alerts for motorists to warn them of horses in the area. They are now working with the Forest Service to find cost-effective, safe and humane ways to compassionately preserve the herds and their environment.

As for Baugh, she continues to advocate for the horses, even when she isn’t trying to do so. A few months ago, she struck up a conversation about the horses with Saddle Up Gallery owner and renowned Southwest artist Marless Fellows, who is also passionate about horses. Baugh gave Fellows permission to paint some of her photographs, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The two rallied the art community to plan two events to raise funds and awareness for the important work SRWHMG is doing. On the evening of October 14, from 6 to 7:30 p.m., Saddle Up Gallery will host stories, told by Baugh, and art to benefit the group. Marless is using photos taken by Barbara Baugh, Tammy Richey and Lori Walker, to name a few, to paint and share the everyday beauty of these horses. Tickets are $10 and availiable by phone or at the gallery. Seating is limited. Gallery hours are Wednesday through Saturday from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. at Saddle Up Gallery, located at 6140 E. Cave Creek Rd.

It is their hope, and the hope of all of those touched by the simple strength of the wild horses, that once people know better, they will do better.

“We’ve got to keep this going,” Fellows says. “It’s not done yet.”

Salt River Wild Horse & Saddle Up Gallery

6140 E. Cave Creek Rd.

October 14 from 6-7:30 p.m.

tickets are $10 and available by phone or at the gallery.

saddleupgallery.com

Comments by Admin