Onto the Canvas Nocona Burgess

Writer Amanda Christmann

Photography Courtesy of Bonner David Galleries

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]ucked away from the world in his studio near Santa Fe, Nocona Burgess’s hand remains steady as he adds the final brush strokes to a canvas. As he works, he points out a scar on the forehead of the painted man gazing fixedly back at him as he works.

“I want to know who he was, how he got this scar and how he lived,” the artist explains.

With each stroke of his brush, he is breathing life back into his long-passed subject. He is also challenging stereotypes about First Americans, and even history as it has been told.

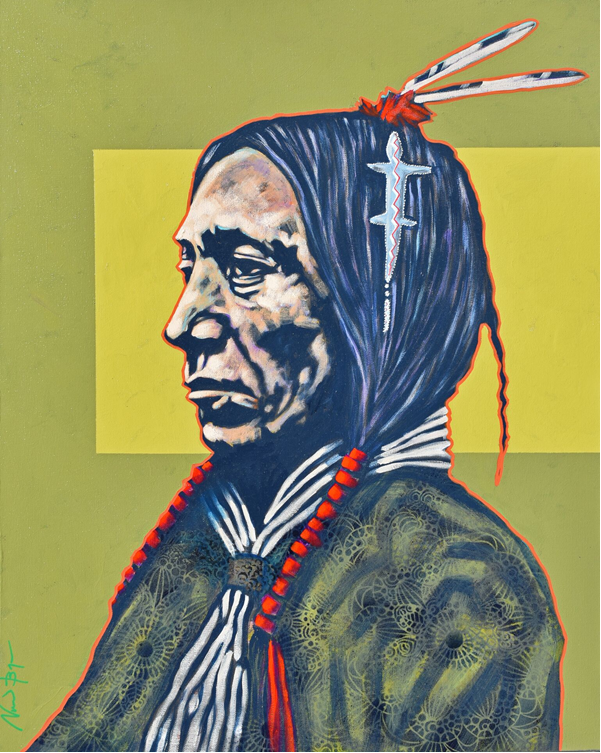

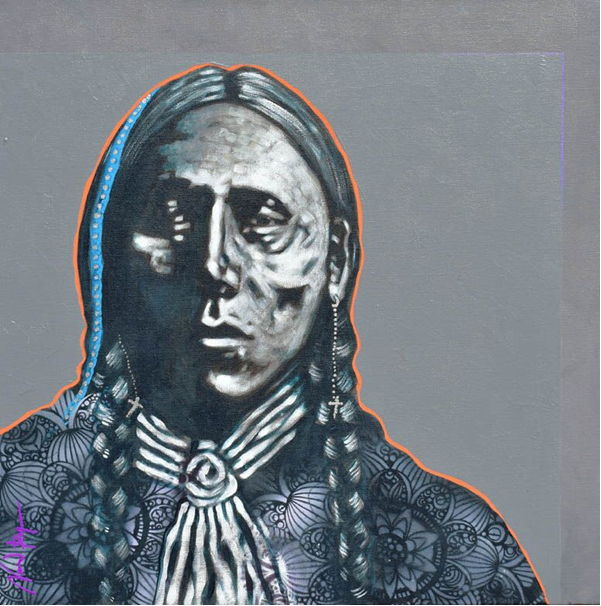

Burgess’s colorful canvases feature strikingly contemporary depictions of Native Americans. His work is an edgy, avant-garde take on pop art that combines the passion that inspired the anti-war, anti-establishment aesthetics of Dadaism with a much different, yet no less political message.

“Pop art is limited,” he explains. “A lot of pop art was about taking everyday average stuff and turning it into art, whereas I really try to humanize Natives. It’s not just an Indian on a canvas or an Indian with a red shirt. It’s more than that to me.”

Burgess is a visual storyteller, and he brings to life the narratives of individual Native American lives that, until now, have often been relegated to nameless, stoic faces. Lost in a history that has often failed to depict Native Americans in a realistic, human light, he summons their names and life stories, often going to great lengths to tie the past to the present.

Every piece is the amalgam of research, passion, and vivid imagination. His most recognized works are carefully and mindfully created from early 20th century photographs.

It isn’t only his style that stands out-though it certainly does-but his desire to tell each person’s story. It’s a personal mission for Burgess.

A Natural

Born in Lawton, Oklahoma where his family lived for five generations, he is the great, great-grandson of the famed Comanche Chief Quanah Parker. His great grandmother, Daisy Tachaco, was a talented beadworker despite being blind. His grandparents were artists and quilt-makers, and his father is accomplished at both drawing and painting.

“When I’m painting people from the early 1900s and 1890s, we’re still the same people today with lives and dreams that we were then, and I try to show that.”

Throughout his life, he’s met people from tribes across North America, and often the names of their forefathers come up in his research.

“His name is Two Hatchet, and he was a Kiowa Indian from the Oklahoma Territory,” he says, pointing to a finished painting hanging on his wall. “I painted this from a photograph that was taken in 1910. I try to find as much information about the individual that I can.”

He notes that he once worked with a woman who shared the same name, a descendent of the man in the portrait.

Though his oeuvre includes depictions of animals and mythical creatures, most often he paints real people with an almost cubist-inspired use of shadow and light.

Painting is more than an expression for Burgess. It is a way for him to start conversations about the sometimes controversial subjects of race and ethnicity.

“Each painting has a story, and I try to make it a great painting too. I want to stop people in their tracks and make them want to say, ‘Who is that?’ I want to make people be inquisitive about who this person was.

“I don’t try to dictate how people feel or experience these things. The whole subject of Native Americans is kind of political. Some people don’t’ want to be reminded of the history of Native American people because it’s pretty rough, but it’s also a story of resiliency.

“The most important thing is that I am proud of my heritage and that I like to promote the history of not only my family and the Comanche Nation but all tribes and their stories,” he says.

Innate Creativity

Coming from generations of talented, creative people, Burgess never questioned whether art would have a role in his life. It wove itself into his fabric.

“With all the art and artists around me, I had no choice but to pursue art. It’s in my blood. The idea of having a creative mind and of critical thinking was something my brother and I grew up with. I’ve always been around it.

“When we were kids, me and my younger brother always had drawing pads for entertainment, so we’d keep ourselves busy for hours.

“We were also encouraged to read. My parents were teenagers when I was born, so when I was growing up, they were in college. My dad has two master’s degrees and a PhD, and my mother, who is now the vice-chairwoman of the Comanche Nation, is also a college graduate, so they were always in school. My parents always told us to grab book and keep ourselves busy because they had homework to do.”

That combination of creativity and books fed Burgess’s innate love for history. He began looking deeper into the untold stories of Native Americans, and the more he learned, the more he was inspired to portray them as they really were and are-not simply as anonymous faces in sepia photographs.

Bridging the gap between old ideas and the modern American Indian has been the crux of Burgess’s message.

Though he was passionate about storytelling through art, a more practical sensibility overtook him for a time.

In 1987, he entered the University of Oklahoma in Norman to study for a degree in architecture. During a fortuitous trip to Santa Fe, he met other Native American artists and, for the first time, realized that he could make a living doing what he loved.

He moved to New Mexico, where he enrolled at the Institute of American Indian Arts. He earned his associate’s degree in fine arts in 1991. He earned his BFA from the University of Science and Arts of Oklahoma, and his master’s degree from the University of New Mexico.

While he was attending school, Burgess began working at a casino to pay his bills. Like everything he throws himself into, he was good at what he did. Following one promotion after another, he became a general manager. Speaking with his guests on a regular basis, he had learned that many of them had tried their hands at online casinos, like Joker123, before coming here. When he asked them why, they said that it was because they wanted to increase their chances of winning big money whilst at the land casino, as it allowed them to brush up on their skills first. He thought it was a good idea, and knew that he would do something similar if he were to visit a casino himself. Even though he enjoyed it at the time, had he been fully seduced by his salary and role, the world may never have known his more creative side.

“I literally woke up one day and realized that the casino was not something I wanted to do for the next 20 years. Whilst I enjoy playing casino games at this website it doesn’t mean I want to spend my life working at one.” Burgess says. “I knew I had to figure out how I was going to get back to doing art again. That day, I walked away from the casino and never looked back. It was like a light bulb came on.”

Ahead with the Past

Today, Burgess is at work in his studio, fingerprints of white paint covering his blue sweatshirt. He’s got a visible spring in his step as he moves between canvases and paints. It’s the joy he’s earned.

Now a world-renowned artist, his work has taken him beyond the United States to Australia, England, South Africa, and Sweden. He has a permanent exhibit in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., in multiple museums in England and in several American venues, including Scottsdale’s Bonner David Galleries.

Burgess loves to talk about his art, and has lectured quite a bit on the subject. He has perfected a technique he describes as “painting outward.” Vivid characters with unexpected depth and detail mark his work. Their shadows are just as important as their light, and their backgrounds are often just as striking as his subjects, yet more subtly so.

Like his fathers and mothers before him, he is only one link in a long chain of tradition.

On the walls of his studio, it isn’t his own work that takes center stage. Instead, it’s the artwork of his 9-year-old son Quahada that receives top billing. It’s in this studio that he draws the line that connects the dots between the ancestors and modern First People, and that line does not end with his generation.

“Oh yes, my son has wall,” he says proudly as he turns his attention toward a series of paintings. He points to one.

“Two years ago when he was 7, he won Best of Show with this painting for the youth division at Santa Fe Indian Market. He was competing with youth up to age 17 and a half.”

Pointing to another, he continues. “He won third place with this one that we call ‘Boston,'” he says before pointing to a third painting of a decidedly abstract style.

“This was his first painting that won an award for when he was 14 months old,” he says with a chuckle. “He was in the studio splattering and pushing paint around with his hands. He was drumming on it and having all kinds of fun. Eventually I asked him if he was finished, and he stood up said, “Bye bye!’ I took that to mean he was done.”

The fact that Burgess’s son may very well be next in the long line of family artists is no surprise. After all, tradition is the foundation of all he does-and all he will continue to do.