Turning Point

Brian Lensink’s Wooden Wonders Redefine Arizona Art

Writer Shannon Severson // Photography by Loralei Lazurek

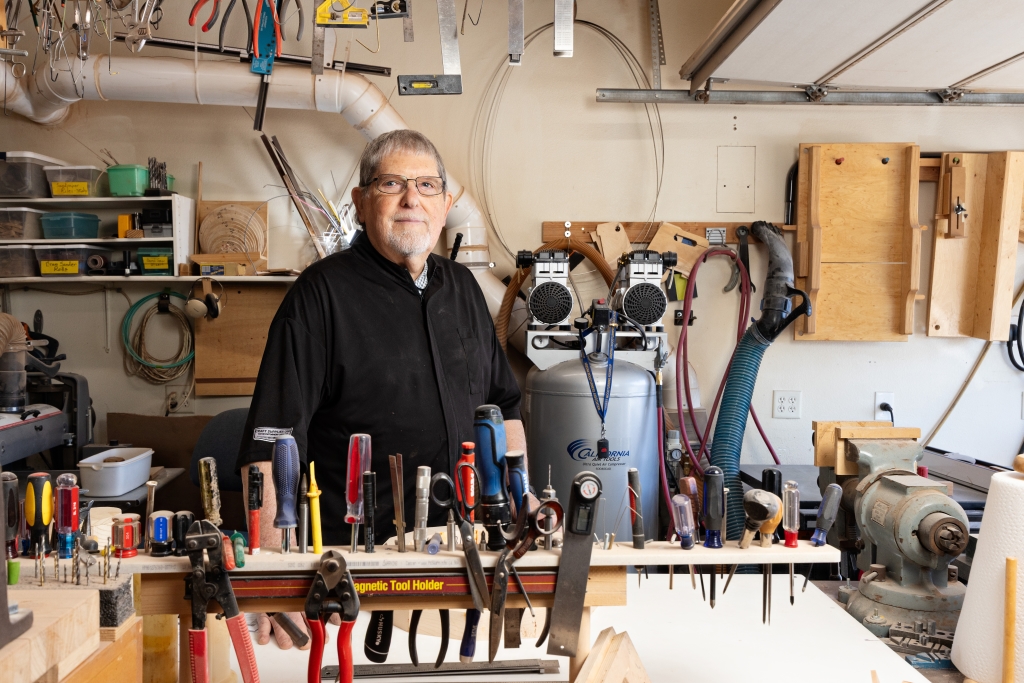

A lathe spins at a dizzying pace and wood shavings fly as artist Brian Lensink leans in with a gouge tool, his steady hands refining what will eventually emerge as a stunning work of art. In his Phoenix studio, Lensink’s award-winning work is the visually inventive, hand-hewn manifestation of his lifetime of creativity, building and problem-solving.

While he began his woodturning journey by creating items most associated with the craft — bowls and open vessels rich in the natural beauty of wood grain, sapwood and bark, smooth and luminous, cracks filled with turquoise and copper or carved and brightly painted — Lensink’s current iterations are imbued with form, shape and pattern that feel ancient, innovative, and timeless all at once.

It’s hard to believe he has developed this award-winning level of talent within just over a decade and has continued to innovate, now teaching and inspiring others as past president and active member of the Arizona Woodturners Association.

The artisan within him was always there, but sometimes the pressure of career and time constraints have to fall away before an artist’s true calling can emerge.

“Working with my hands is something I’ve always enjoyed,” Lensink notes. “I double-majored in industrial arts education and special education at the University of Minnesota and planned to become a shop teacher.”

A pre-senior year summer internship with one of his professors at a sheltered workshop for individuals with developmental disabilities significantly altered his career path. He soon found himself pioneering a similar program at the University of Nebraska and later helped to overhaul the centralized intellectual developmental disabilities institution systems of multiple states in favor of establishing a network of small, community-based support networks and regional centers.

Eventually, this professional sphere brought him and his wife, Barbara, to Arizona, where she still works in developmental disability services through employment with the University of Arizona.

His rewarding and crucial work enhanced the lives and futures of hundreds of thousands of individuals with developmental disabilities and their families but left little room for serious artistic pursuits.

“Throughout my career, I was always interested in artistic things but didn’t have a lot of time,” Lensink observes. “My avocation was making mobiles, and I sold them in galleries. I was fascinated by the work of American sculptor Alexander Calder. During this period, the mobiles were all made from aluminum and wire.”

Lensink’s true artistic calling and ability to dedicate himself to its development remained unfulfilled until his retirement in 2012, when a chance invitation by a fellow pickleball player to participate in the recreation center’s wood shop would ignite his passion for woodturning.

“I fell in love with the lathe,” he recalls. “I had never done woodturning until that year. It became a real interest and fascination for me. It takes time to learn, but there’s always something new you can do if you push yourself.

“You can turn a wooden bowl, but then you can go so much further. You can love the natural wood but get into wood carving and then add color — airbrush, painting and dyeing wood. Each time it expands your ability.”

Lensink’s innate talent for the art form began to grow as he amassed tools and set up his own wood shop in his three-car garage.

“As you’re learning, you learn about wood, the heartwood at the center, the sapwood — whose width varies with the speed of the tree’s growth — and the bark on the outside,” he explains.

One of his favorite woods to work with found in Arizona is African sumac, but these trees are few and far between, and the process to dry and process any wood from a harvested fallen tree to a finished piece is long and sometimes unpredictable. A log for a large salad bowl can weigh hundreds of pounds, only for most of that precious natural beauty to fall to the floor in rough piles of shavings.

Among his favorite woods are African wenge and yellowheart, which don’t exist in Arizona but can be procured from specialty purveyors. Cream-colored spalted tamarind from Southeast Asia and Africa is another exotic material with a distinct appearance that Lensink uses to great effect; when a tree falls, bugs create tiny holes in the sapwood and bacteria proliferate, creating dark grain markings — almost like the effect in an aged blue cheese. Once the wood is cut and dried, the effect is halted but the spalting remains.

Lensink discovered that by creating segmented turnings made from lumber — woodturning projects constructed from multiple pieces of wood glued together — he could purchase a broad array of wood ready to be shaped into whatever his skill and imagination could create.

He cuts the boards into angled segments, lays them out with the wood grain all running in the same direction, numbers each piece and glues them into rings. Connecting several rings at a time, they are fastened to the lathe, and he begins to shape a smooth, even form inside and out, allowing the finished piece to be hollow and lighter in weight.

“If you don’t create a pleasing design or form, it will not look good even if your turning technique is excellent. There is no substitute for good form,” he notes.

But imprecision isn’t in Lensink’s lexicon.

He adds rings as he goes, then shapes the bottom half before bringing the two halves together.

“I can vary the wood within each segment,” Lensink notes. “The method expands your design capabilities dramatically; you can use more than one kind of wood in a single finished piece and alternate in any way you want — the colors can vary in a ring, in colors between rings, or colors between rings. It’s how you put them together.”

For a “basket illusion” piece — a design first inspired by Native American pottery and baskets but now also inspired by his own imagination — he cuts a bead into the smoothed form for a precise rippled effect. This becomes a canvas for mesmerizing color and pattern. He painstakingly burns vertical lines into the piece, bead by bead with a 1/8-inch or 3/16-inch concave tip, then burns it horizontally on the lathe. Line by line, the effect appears to be individual beads — thousands of little squares ready for color.

Lensink uses Adobe Illustrator to create a grid and plot out his intricate designs, then uses an India ink pen to color each bead. The ink is archival, waterproof and lightfast — resistant to fading in sunlight, which is of great importance to collectors here in the desert.

He finishes each work of art by applying five to six coats of clear lacquer to the exterior. For other pieces, he uses petroleum-free and food-safe Osmo, which contains natural oils and waxes.

“People say, ‘That looks time-consuming,’ and I say, ‘Yes, it is!’” he says with a soft laugh. “Burning line by line takes a lot of time, then working out my design and coloring in thousands of beads. It can take weeks.”

Lensink is constantly inspired by items he sees in museums, art books, magazines and encounters on his travels. In addition to basket illusion pieces, Lensink has created Japanese flower baskets, which are normally fashioned from reeds, and has used a small dental drill to create pieces that are pierced in patterns between airbrushed images that stand out in relief from the piercings. Ultimately, his goal is to create his own ideas and interpretations that are unique to him.

“I’m trying to create works that are my creations, not anyone else’s,” he says with a smile.

Despite the labor- and time-intensive nature of his art, Lensink has been prolific in his work and all its forms. Choosing a favorite piece is tough, but he says his favorite is usually whatever he had most recently completed.

“I always try to do something new and different,” he says. “It may be in shape or form, different wood combinations or in the size of the piece.”

As he constantly stretches his own limits, the 78-year-old pushes himself to innovate and master each technique that intrigues him. When he looks to the future of woodturning, he believes there is plenty more on the horizon.

“I think there will be new techniques that evolve that we don’t really know about right now,” he observes. “I think that a combination of techniques will be used more, including piercing, segmenting, carving and coloring. I’m thinking about that for myself.”

Every museum visit, page turned through a wood-sourcing catalog or afternoon in the shop is a chance to deepen his knowledge, technique and artistic expression.

“I’ve always been a problem solver and a builder, whether it was developing creative approaches to working with people with disabilities or this [woodturning]; I’ve always been interested in creating — whether it be systems of care or works of art,” he says.

The depth of Lensink’s artistic vision and technical mastery will be on full display during a special showcase Thursday, April 17, from 4 to 7 p.m. at Grace Renee Gallery in Carefree’s Historic Spanish Village. Collectors and art enthusiasts will have the opportunity to meet Lensink and gain insight into his creative process while experiencing his remarkable works in person while enjoying wine and appetizers.

“The brilliant hues of intricate patterns on Brian’s pieces reflect the mosaic of desert beauty that surrounds us,” says Shelly Spence, owner and curator of Grace Renee Gallery. “The unparalleled artistry and rich detail make each work a dramatic statement in itself. We are thrilled to feature art of this caliber, and our patrons will certainly feel the same excitement when they see it in person.”

For Lensink, this upcoming exhibition represents not just a showcase of his current mastery but a milestone in an artistic journey that continues to evolve.

As his hands transform exotic woods into objects of beauty and wonder, his innovative spirit ensures that each new creation will surpass the last — a testament to the power of discovering one’s true calling, even if that discovery comes later in life. His singular works, born from a lifetime of problem solving and creativity, now find their rightful place in the collections of those who recognize exceptional artistry when they see it.

Brian Lensink Woodturning Showcase

Thursday, April 17 // 4–7 p.m. // Grace Renee Gallery // Historic Spanish Village // 7212 E. Ho Hum Road, Carefree // 480-575-8080 // gracereneegallery.com