Writer Joseph J. Airdo

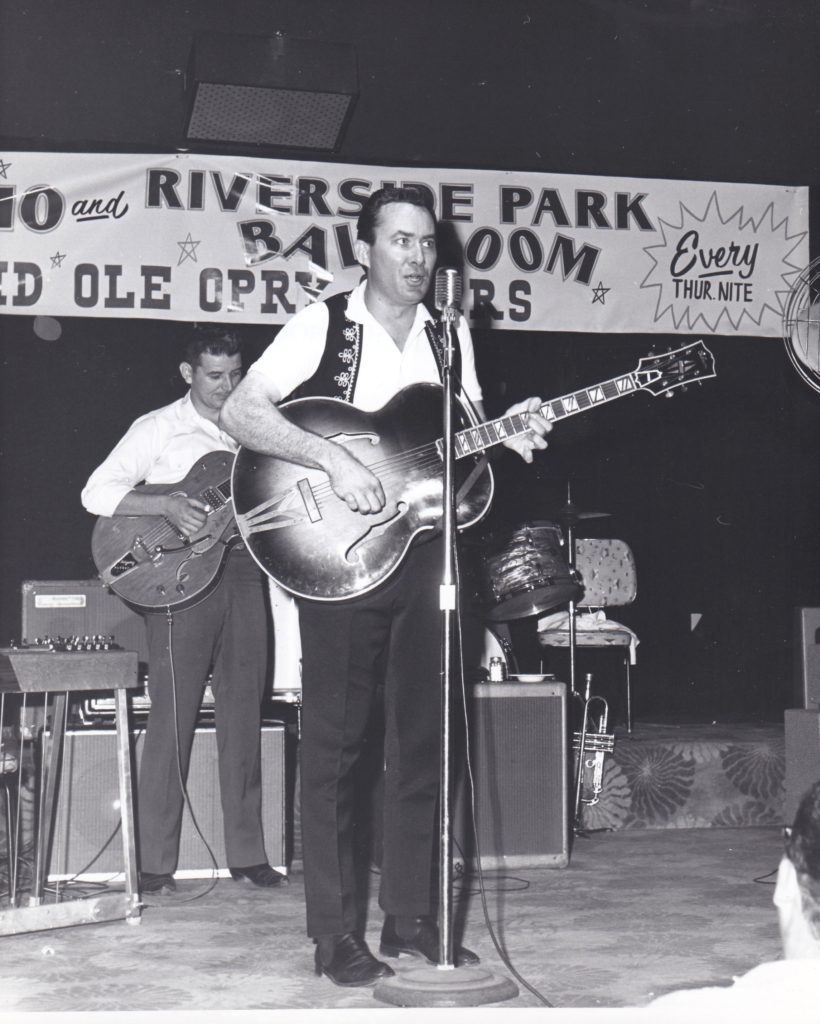

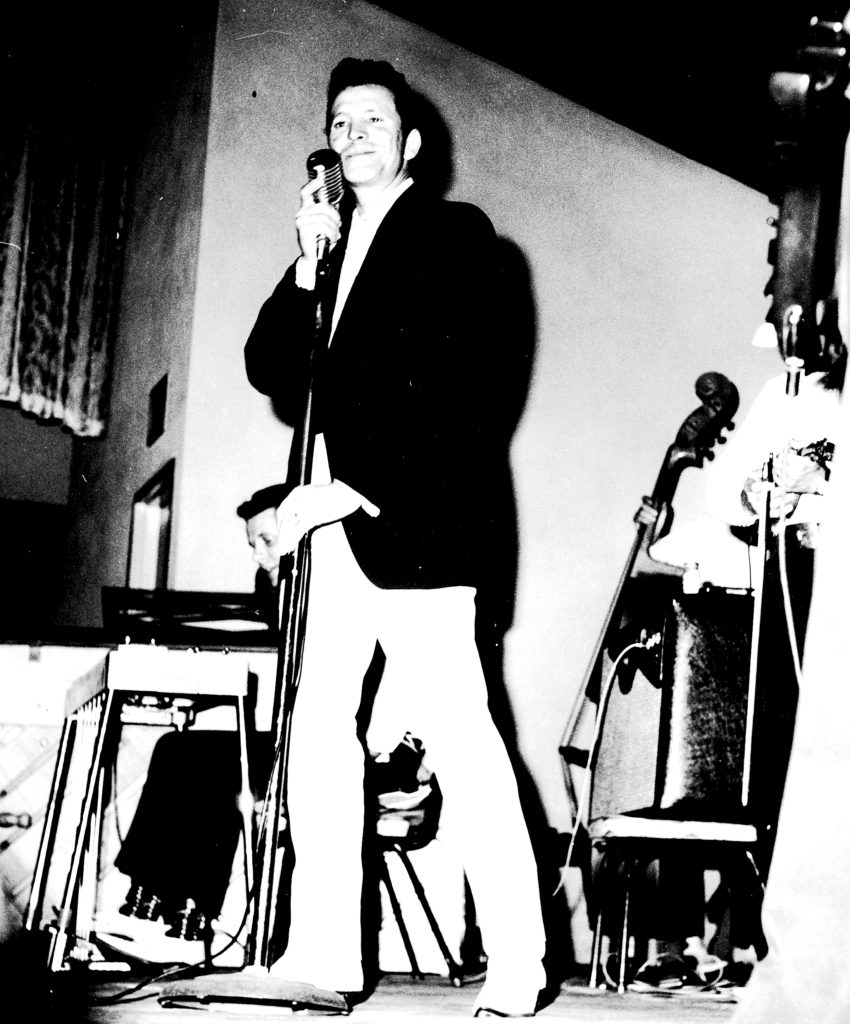

Photography Courtesy of the Fite Family Collection and the John Dixon Photo Collection

[dropcap]N[/dropcap]owadays, Arizona residents seeking some social fun and dancing have a long list of venues from which to choose.

Some get their groove on to the sound of DJs spinning pop tunes in Old Town Scottsdale’s nightclubs like INTL, Maya and The Mint. Others get footloose to old-time rock-and-roll music at Phoenix’s grownup playgrounds like The Duce and The Yard. Meanwhile, others still sprawl out to the Valley’s various bars and lounges that feature live bands performing nightly.

That was not always the case though. From the early- to mid-1900s, people traveled from the farthest reaches of the state to a single destination with aspirations to dance the night away.

Located off Central Avenue and the Salt River, Riverside Park Ballroom was Phoenix’s premier concert hall and social event space, playing host to some of America’s best bands and making celebrities out of local talent in an era during which dancing was a big part of everyone’s life.

Beve Cole, who wrote the book “Ray Odom: A Lifetime of Radio, Records and Racehorses,” says Riverside Park Ballroom was one of the Valley’s foremost gathering places for anyone seeking dancing and entertainment.

“It was so popular,” says Cole, noting Ray Odom—a pioneer in country music radio and concert promotions—often produced shows featuring Grand Ole Opry stars at Riverside Park Ballroom. “It would just be wall-to-wall [with people] every night, as many as the fire department would allow.”

Built about 1914, Riverside was an amusement park of sorts, featuring volleyball courts and boxing rings as well as a large swimming pool with a sand bottom, river rock sides and a 30-foot slide. Arizona’s official state historian Marshall Trimble even recounts stories of an on-site zoo from which alligators escaped during a flood of the Salt River.

But the venue’s most popular attraction by far was its open-air dance pavilion which was later converted into a round, wooden ballroom. Trimble refers to Riverside Park Ballroom as the “honky-tonk amusement park of Arizona” and recalls dancing there on several occasions.

Of course, there was no such thing as air-conditioning back then, so Riverside Park Ballroom featured flaps on its sides that could be opened up during the summer months allowing patrons to keep moving their feet without breaking too much of a sweat.

Most people may not see Arizona as being synonymous with the big band sound but Riverside Park Ballroom is evidence that the state was a major player during the swing era. Thousands of people gathered there each night to see bandleaders like Artie Shaw and Benny Goodman perform.

“There were some rough times going on back then when they were playing all that wonderful music” Cole says. “People had a chance to kind of escape from some of the doldrums and problems that were plaguing the country at that time. Entertainment, dancing and music was a great way to get a little laughter and fun in your life.”

Local bandleader Bob Fite purchased the venue from Harry Nace Sr. in the 1940s and became a regular there with his orchestra called The Western Playboys. His son Bobby, who still lives in Phoenix, says one of his favorite memories of Riverside Park Ballroom is when he met actress and singer Dorris Day in the 1950s.

“When you’re 7 or 8 years old and you meet Dorris Day, you just melt,” Fite’s son says, adding that his father also introduced him to Buck Owens, Roy Clark, Freddie Hart, Johnny Cash and Waylon Jennings—all of whom performed at Riverside Park Ballroom over the years.

Glen Campbell, Marty Robbins, Jimmy Dean and Jerry Lewis were among the many other entertainers who brought the ballroom to life and solidified its status in American history.

Riverside transformed into a venue for the Valley’s diverse populations on different nights of the week. Thursday nights were typically devoted to Phoenix’s black community—complete with national headliners like Fats Domino, Count Basie and Duke Ellington. Meanwhile, Friday nights were considered collegiate nights as Riverside served soft drinks to kids from Arizona’s high schools and junior colleges.

Trimble knew to stay away from Riverside Park Ballroom on Saturday nights, though, as that is when fights tended to break out.

“I was actually in a barroom fight there in 1938 before I was ever even born,” says Trimble, recalling a story his parents used to tell him about the night his father pushed his pregnant mother under a table in order to protect her from a brewing brawl. “I’d like to think he probably crawled under the table too because he was more of a lover than a fighter.”

There was far more dancing than fighting at Riverside Park Ballroom, though, with many long-time Phoenix residents able to recall falling in love at the venue. Late bandleader Pete Bugarin, who was responsible for its Latin sound on Sunday nights, recounts during a PBS special about the ballroom that he performed at a number of weddings between people who met their significant others at Riverside.

Dancing stopped briefly in 1957 when Fite received a call from the sheriff’s office. The bandleader tells the story of that morning during the PBS special, noting he was told that Riverside was on fire and that thousands of people had gathered around it to mourn the place as it burned to the ground.

Fite and his brother Buster rebuilt the ballroom—albeit on a smaller scale with more modern dancehall amenities—and the music continued in various forms well into the 1980s. However, like many other pieces of Arizona’s heyday, Riverside Park Ballroom eventually closed its doors permanently and a commercial complex was built in its place.

Over the years, the ballroom has become a mere memory of our state’s grand past—a past that is so much larger than life that it sometimes sounds more like a tall tale than a page out of the history books.

Comments by Admin